Ron Craig, PhD

Edinboro University of Pennsylvania

Angelica Perez, MA

Edinboro University of Pennsylvania

Brett Gatesman, MA

Edinboro University of Pennsylvania

Texting or Short Message Service (SMS) is a popular form of communication; like all forms of communication, it is capable of conveying information, facilitating relationships, sharing emotions, and even can be used for deception. The use of deception in SMS is not well understood and raises many questions. First, is SMS used to deceive, to whom, for what purposes, can it be detected and is it perceived differently than lying in person? This study surveyed 195 undergraduate students regarding deceptive texting behaviors. Questions addressed both the participant’s use and experience with deceptive SMS; in addition, moral and emotional perceptions of SMS deception were assessed. The results highlight the way deception is being used in SMS and the relationship with the use of SMS to deceive and views of its wrongfulness and impact on others.

Keywords: Texting, SMS, deception, lying

- Citation

- Authors

Ron Craig, Ph.D. joined Edinboro University in 1997 after earning his Ph.D. in Psychology from the University of Utah, focusing on forensic developmental psychology. He also earned a BA in Psychology from Boise State University in 1991. His research interests are in the areas related to forensic and developmental psychology, including interviewing children, detection of deception in juveniles, and the role of technology in the courtroom. Dr. Craig has published in journals Psychology, Crime & Law, Polygraph, Applied Developmental Sciences, and the Journal of Credibility Assessment and Witness Psychology. In addition, Dr. Craig has presented at several regional, national, and international conferences including the American Psychology and Law Society, as well as the American Psychology Association. He has an active undergraduate research program in forensic psychology resulting in numerous presentations and publications with undergraduate collaborators. Dr. Craig was also named Edinboro University Advisor of the Year for 2014 and was the 2009 recipient (with University of Utah research group) of the APA’s John E. Reid Memorial Award for distinguished achievement in polygraph research, teaching or writing.

Angelica Perez, M.A. is an Academic Advisor at Thiel college and a current Doctoral Student at West Chester University in the Doctoral of Public Administration program. A double alum from Edinboro University, she earned her Master’s Degree in Counseling and her Bachelor’s Degree in Psychology. Prior to entering Higher Education, she worked as a therapist in a number of settings including at-risk youth and drug and alcohol.

Brett Gatesman, M.A. completed his Psychology undergraduate studies at Edinboro University while working with Dr. Ron Craig, then went on to obtain a Master’s in Industrial/Organizational Psychology from the University of Akron. During his time at Edinboro, Brett worked with Dr. Craig on studies relating to using reaction time to detect deception, as well as examining deception through electronic mediums. Currently, Brett is an Industrial/Organizational Psychology practitioner at Wonderlic, Inc. He works as a Senior Consultant and helps organizations implement, refine, and analyze their hiring processes. Brett’s professional interests include applicant reactions, job performance analysis, and data visualization.

Brett Gatesman, M.A. completed his Psychology undergraduate studies at Edinboro University while working with Dr. Ron Craig, then went on to obtain a Master’s in Industrial/Organizational Psychology from the University of Akron. During his time at Edinboro, Brett worked with Dr. Craig on studies relating to using reaction time to detect deception, as well as examining deception through electronic mediums. Currently, Brett is an Industrial/Organizational Psychology practitioner at Wonderlic, Inc. He works as a Senior Consultant and helps organizations implement, refine, and analyze their hiring processes. Brett’s professional interests include applicant reactions, job performance analysis, and data visualization.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Ron Craig Ph.D., Department of Psychology, Edinboro University of Pennsylvania, 210 E. Normal St., Edinboro, PA 16444. E-mail: rcraig@edinboro.edu . A portion of this research was presented by the first two authors at the Western Pennsylvania Undergraduate Psychology Conference in April 2011 at Westminster College, New Wilmington, PA

Introduction: The Use of Texting as a Medium for Deception in a Survey of College-Age Texters

“u coming over?” “cant, have to study LOL” “k”

People, of all ages, find texting or Short Message Service (SMS) to be a valuable form of near instant and constant communication via cell phones and other equipped wireless devices (Merkel, 2010). The SMS allows someone to send a short message from anywhere there is cellular or wireless access to another individual’s SMS capable device for which the sender has the phone number. As these messages are limited in length (140 characters), it has even given rise to a new language of abbreviated words called “textese” (Thurlow, 2003), which the sender and recipient must both know. SMS use has increased rapidly, with the number of texts worldwide tripling from 2007 to 2010 to 6.1 Trillion (ITU, 2010). Just as with other forms of electronic communication, SMS allows for the sharing of information, building and facilitating relationships, and expressing emotions. Research has found SMS can help support students as they transition to college (Harley, Winn, Pemberton, & Wilcox, 2007), and that SMS is often used by females to promote intimacy in relationships whereas male utilize it more to initiate relationships with others (Morrill, Jones, & Vaterlaus, 2013). However, as with most other forms of communication, SMS also has the potential for being used as a tool to deceive others.

The use of deception has been identified in many forms of technology-based communications including email, instant messaging, and social networking sites. There is a growing body of research looking at deception in many of these areas, particularly online dating and social networks (Caspi & Gorsky, 2006; Lu, 2008; Naquin, Kurtzberg, & Belkin, 2010). However, deception in a SMS comes with unique elements that are not commonly found in many other online or even face-to-face communications. Many forms of online communications can lure the individual into a sense of anonymity; sometimes the deceiver has never met or known the person on the other end of the interaction outside of the online environment. Individuals may be communicating a false persona, and they may never anticipate meeting the person outside of the online environment. However, SMS is a more personal type of communication, most often sent between people who know each other at some level outside the SMS environment (Pettigrew, 2009).

Research by Birnholtz, et al. (2010) and French, Smith, Birnholtz, & Hancock, (2015) indicates that one of the primary uses of the SMS messages is to facilitate social relationships outside the SMS interaction. In addition, due to the limited length of the messages, a unique language “textese” (Thurlow, 2003) or text speak has evolved in which phrases and words are abbreviated to just a couple of characters (i.e. LOL for lots of laugh or laugh out loud). This new speak allows for some ambiguity in meaning and is, in some ways, dependent on the recipient’s knowledge of the textese being used. The limited size of the messages can also result in ambiguities in the meaning of messages (Birnholtz, et al., 2010). For example “Can’t have to study LOL” could be “I can’t and I have to study,” “I’m not going to study but can’t” and so on. In addition, it appears that the nature of the interaction is also unusual compared to some other forms of technology communications (i.e. email), in that a “conversation” in real time can occur. This also can be a source of deception, as pointed out by Biriholtz, et al., such as when the receiver of a SMS lies about when they read the sender’s message. Because of the unique nature of SMS exchanges, they are seen as more conversationally involved than other digital exchanges (Reid & Reid, 2010). However, there is very little research regarding how SMS is used in deceiving others. Wise & Rodriguez (2013) found that a significant number of participants had both lied and believed to have been lied to in SMS messages but were less likely to have lied in a business communication compared to a personal one. Most participants also indicated that they did not discover that an SMS was deceptive until the lie was exposed in some other way. Thus, the questions arise if, in fact, SMS is used to deceive: 1) is it easier to use and/or be believed than face-to-face communications, 2) how is it being used to deceive, to whom, and 3) what if any differences are there in the perception of its wrongfulness.

Research on the use of deception in emails and other types of Internet-based communication indicate that most individuals perceive a larger amount of deception among Internet-based communications than what is reported in studies where people report how much they actually deceive in these same forms of communications (Caspi & Gorsky, 2006). Caspi and Gorsky (2006) argue that Internet-based communications may provide less social obligation than their face-to-face counterparts, providing communicators with a lessened sense of responsibility when deceiving. Lu (2008) also suggests that the level of dependency on such online communications may have an effect on whether or not an individual will use deception in this type of communication. Naquin, Kurtzber, and Bekin (2010) found that, compared to correspondence via paper and pen, people were more willing to lie in an e-mail, felt more justified in doing so and believed they were less likely to be detected. While texting has similar characteristics to e-mail as a text based system, it is also used more in relational communications (Pettigrew, 2009) and, thus, may differ in how its function is perceived by the users.

In one study on SMS and deception, Birnholtz, et al. (2010) reviewed recent text messages sent by participants and found that the 10.7% of the texts sent were classified by the sender as lies. Of these, almost a third were what Birnholtz et al. termed “Butler lies,” intended to manage social interactions with people they knew. They found that these lies often were related to deception about time, place or activities and were told to maintain or facilitate the social relationship with the recipient. Many of the SMS lies were similar to lies that might be told over the phone. The authors did find that many of the text lies were not simple replies but fabricated to increase plausibility and to maintain the social relationship. They also note that participants took advantage of the more ambiguous nature of the SMS format to facilitate deception. Examples of this ambiguity include when or if the SMS was read in addition to semantic and location ambiguity.

Research into specific interpersonal components of SMS finds there are consistencies in the perceptions of hurtful text messages sent to friends and other forms of hurtful communication (Jin, 2013). With a college age sample, Jin found that hurtful texting was a common occurrence and negatively impacted the students’ interpersonal relationships. Two important factors of message perception included the intent of the message and satisfaction with the relationship in question. For more specific types of SMS like “sexting,” Drouin, Tobin, & Wygant, (2014) found that almost half of the participants who reported having engaged in sexting had lied during the sexting to their committed partner. The authors report that women in their study were more likely than the men to have lied while sexting with the type of lie intended to serve or benefit the partner in the communication.

The present study is a survey of SMS users designed to explore the patterns of deception used in their SMS communications; examining to whom they deceive, what they tended to be deceptive about, how they feel about being deceived or deceiving others in a SMS, and other characteristics of deceptive texting behavior. This survey also investigated whether individuals report being able to identify when they are being deceived via SMS and their perceptions of deceptive SMS, along with assessment of wrongfulness of SMS deception compared to a lie told to a person’s face.

Method

Participants

The study surveyed 195 undergraduate students enrolled in undergraduate psychology courses at a western Pennsylvania university. Participants were asked to complete an anonymous online survey, the purpose being to develop a better understanding of how students use SMS for purposes of deception. Students were offered extra credit for participation, and an alternate exercise was available for those who elected not to participate.

Materials

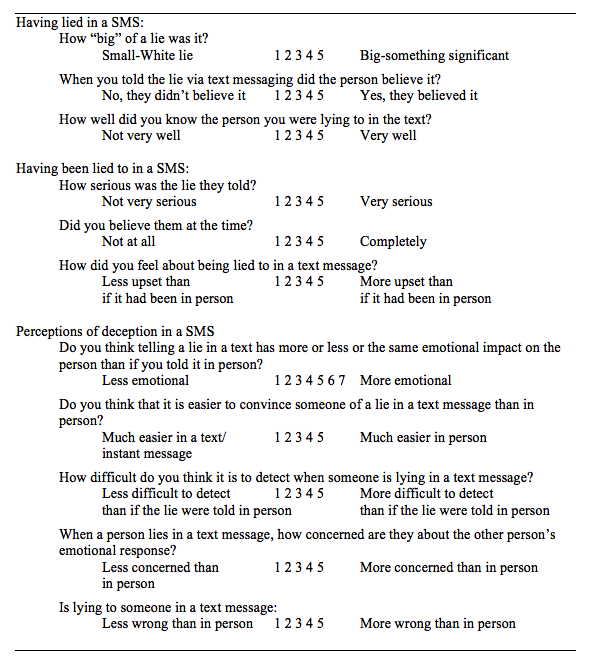

The present study used a 38 question online survey to investigate the use of cell phone SMS to deceive. Questions included demographics, frequency of SMS use, use of “textese” in SMS conversations, whether they had lied during a SMS “conversation” and questions relating to that lie, as well as whether they had been lied to during a SMS “conversation” and questions relating to that particular lie ( See Table 1). In addition, participants were asked questions regarding their perceptions of lying via SMS as well as emotional components of text messaging deception (Table 1). Participants responded with a yes/no, a Likert scale rating, or open-ended response depending upon the question.

Table 1. Select Questions from Online SMS deception survey

Procedure

Participants were recruited by sending an email request to general psychology classes that provided a brief description of the study and a link to the anonymous online survey. Participants read informed consent online following the URL provided by the researchers and agreed to the terms and conditions of the informed consent prior to beginning the survey. Participants then answered questions related to the frequency of use of texting, the use of “textese” during texting, and whether or not the participant had lied to another individual using SMS, as well as whether or not the participant had been lied to via SMS. The survey had a hierarchical structure. For example, a participant who indicated they had not tried to deceive another in an SMS would not be asked further about their deceptive SMS behavior. The survey responses were anonymous. They were collected, coded and entered into SPSS for data analysis.

Results

The present experiment was exploratory in nature and designed to investigate trends among cell phone use and deceptive SMS messages. Of the 195 responses received, 193 reported using SMS as a means of communication; the two who reported not using SMS were dropped from subsequent analyses.

Demographics and familiarity with SMS:

For those participants who reported using SMS messaging, the mean age was 19.98 (SD= 4.18), and ranged from 18 to 51; 70.5% were female and 29.5% male. The mean age for beginning to SMS was 15.64 (SD= 4.75) and ranged from 8 to 48, with the mean number years texting being 4.51 (SD= 2.10). When asked how familiar participants were with texting 93.8% responded as being very familiar (either 4 or 5 on a 5-point scale), and 82.9% used “textese” (i.e. LOL, OMG…). When asked how often they text (on a five-point scale) 91.1% reported many times a day (4 or 5 on the scale).

Participants’ deceptive SMS behaviors:

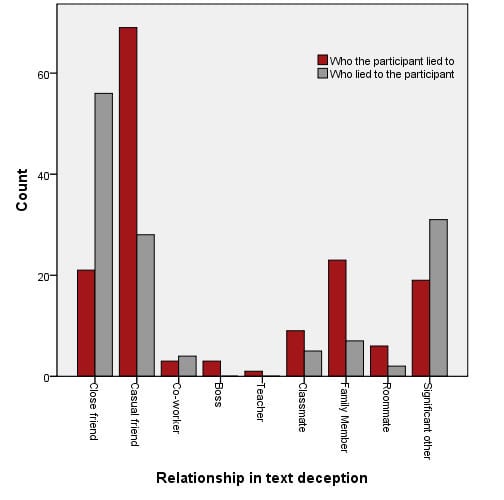

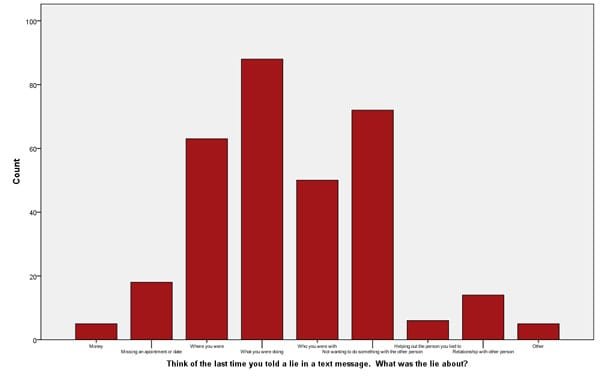

One hundred fifty-five participants (80.3%) reported telling a lie via a SMS message. These lies were most often told to casual friends (44.8%) (Figure 1), whom they knew moderately to very well (69.5%) (indicating either a 4 or 5 on a 5-point scale) at the time and had spoken to the individual in person before (98.7%). Figure 2 represents what participants reported lying about via SMS. The most prevalent lies regarded what the texter was doing at the time (26.5%) and not wanting to do something with the text recipient (23.2%). This lie was most frequently reported as small or insignificant in nature with 71.6% reporting a 1 or 2 on a 5-point scale (M = 2.04, SD = 1.01). One hundred twenty-eight participants (66.3%) reported the person they lied to never learned the truth. In addition, 58% of participants reported telling a similar lie to someone else. A Mann- Whitney U test indicated participants who lied via text were more familiar with SMS (Mean Rank = 98.74) than those who hadn’t lied (Mean Rank = 82.55), U, = 2396, z = 2.765, r = .200. A Mann-Whitney U test identified a difference between how well the deceiver knew the person and if the person they had deceived ever learned the truth. Participants were more familiar with those who did discover the truth (Mean Rank = 103.04) than those who didn’t (Mean Rank = 71.52), U = 899, Z=-3.389, p < .05, r = .275.

Figure 1. Relationship between texter and person deceiving or being deceived

Figure 2. Topic of most recent texting lie told

Participants’ being deceived via text:

One hundred thirty-seven participants (71%) reported having been lied to in a SMS message, with close friends being the most common perpetrators (42.1%, Figure 1), however, 51 (26.4%) of respondents reported they didn’t know if they had been lied to or not. When asked, on a five-point scale, how serious the lie was 40.9% gave a score of 3 on a 5-point scale (M =3.00, SD = 1.25) and when asked how upset they were about being lied to 52.2% gave a 3 (1=less upset than in person, 5=more upset than in person respectively). Participants’ initially believed in the SMS lie and the lie was most often discovered later from another source (48.9%) with only 28.5% reporting they could tell from the SMS itself. Ninety-nine percent reported having spoken to the deceiver in person before and the majority (56.2%) reported having lied in a SMS message to the person who lied to them. There was a significant relationship between how they felt about being lied to in a SMS and the seriousness of the lie (Spearman’s r = .417, p<.000). In addition, the more serious the lie was, the more likely it was to be believed at the time of the deception (Spearman’s r = .283, p = .001).

Perceptions of deception in text messages:

When asked about the emotional impact on lying to a person via text or in person, participants most often rated a 4 (36.3%) on a scale from 1 to 7 (M = 3.67, SD = 1.57). When asked about their concern regarding the recipient’s emotional response 63.3% reported less concern (1 or 2 on a scale from 1 to 5). The majority felt there was no difference in wrongfulness of lying in text or via person with 69.4% rating a 3 (M=3.16, SD = .92) on a 5-point scale. When asked how difficult it is to deceive in a text, the majority (64.3%, M = 2.17, SD = 1.35) felt it was easier (1 or 2 on a 5-point scale) than in person, and that it is more difficult to detect deception in an SMS than if it were in person (54.4%, 4 or 5 on a 5-point scale, M = 3.49, SD = 1.35). There was a significant relationship between the perceived emotional impact of the SMS lie and ease of deception in a SMS (Spearman’s r = .189, p = .008), where the less emotional the SMS lie was, the more difficult SMS lies were to detect. A similar relationship was present with those believing it is easier to deceive in SMS, seeing the deceiver as less emotionally concerned about the deception (Spearman’s r = .171, p = .027). Finally, as would be expected, there was a reasonably strong relationship between how wrong they felt lying in a SMS is and the emotional impact of the lie (Spearman’s r = .413, p < .000), where the more wrong SMS lying was seen the more emotional impact it was felt to have.

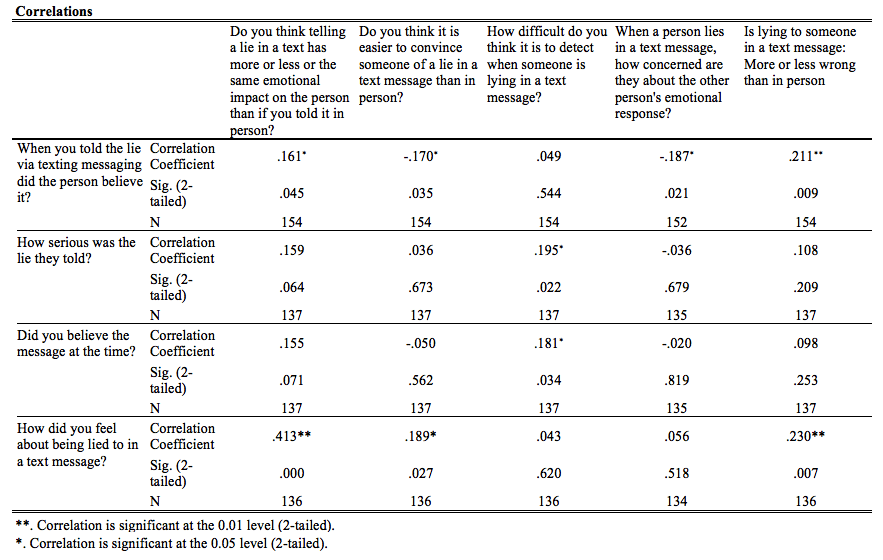

Relation between participant’s deceptive behaviors and perception of text deception:

A Mann-Whitney test indicated that those having told a lie in a text felt that text lies had less emotional impact (Mean Rank = 92.10) when compared to the perception of emotional impact for those who did not lie (Mean Rank = 116.99) U = 2185.5, Z = 2.535, p < .05, r = .182. The perceived difficulty to convince someone of a lie via text messaging was higher (Mean Rank = 98.72) if the participant’s lie had been discovered than if it had not (Mean Rank = 72.76) U = 1057, Z = 2.875, p < .05, r = .232. How much the participant’s deception was believed (rated on a 5-point scale) was correlated significantly with 4 of the 5 questions related to perceptions of SMS deception (Table 2). No other responses to the participant’s lie were correlated with their perceptions of SMS deception (alpha = .05).

Relation between participants having been deceived and perception of text deception:

Perceptions of SMS deception were related to three aspects of having been deceived in a SMS: how the participants felt about being lied to, how serious they felt the lie was, and whether or not they believed the lie at the time. How participants felt about being lied to correlated with the emotional impact of SMS deception, ease of deception in SMS, and wrongness of SMS deception (Table 2). Both how much they believed a lie and the perceived seriousness of the lie were correlated with how difficult participants felt it was to detect deception in SMS (See Table 2).

Table 2. Correlations of being lied to in an SMS and perceptions of SMS lying

Discussion

Based on the responses from this survey, it is clear SMS is being used as a communication medium for deception. Consistent with relational models for use of SMS put forth by Wise & Rodriguez (2013), Pettigrew (2009), and Birnholtz, et al. (2010), individuals who have told a lie via text, lie more often to casual friends and family members with whom they have spoken in person and know fairly well. When lying, individuals more often lie about what they were doing or to avoid doing something with the person with whom they were texting. This is consistent with the notion of “Butler lies” intended to maintain social relationships (Birnholtz, et al., 2010, French, Smith, Birnholtz, & Hancock, 2015). Birnholtz, et al. argues that the inability to know where the texter is located and the limited length of the message facilitates the use of the SMS as a tool for deception of this kind. This study supports the nature of the lies told and the target of the lies told in keeping with the Birnholtz, et al. model. In addition, findings that closer friends were more likely to discover the truth may indicate that close friends have more avenues to learn the truth. Future research could explore the impact of these discoveries of deception in texting on close relationships.

There were similarities in our findings regarding SMS to research conducted on other forms of electronic deception. Overall, SMS deceivers saw the lie they told as insignificant and with less emotional impact on the other person than email deception, which is consistent with research by Naquin, Kurtzber, and Bekin (2010). Also, the participants appeared to have a repeat pattern of telling similar SMS lies to more than one individual, which may point towards the uses of SMS deception as a vehicle to maintain social relationship. Generally, the participants reported that telling a lie in a text has no more or less emotional impact on a person than telling the same lie face to face. However, it appears from these findings that individuals may think it is easier to deceive via text than in person as well as more difficult to detect deception in a text message.

There were differences in participants’ perceptions about SMS lies based on whether or not the lies had been believed. Those who reported being successful using SMS for deception were more likely to indicate that SMS deception is easier to perpetrate than a face-to-face lie. Interestingly, though, success in SMS deception also correlated with increased negative beliefs about the impact of SMS deception; seeing it as having more emotional impact, believing it to be more unethical, and perceiving deceivers as less concerned about the other person’s emotions than for a lie told in person. Thus, successful deceivers saw SMS deception as more negative than deception in person compared to unsuccessful deceivers. However, there was no relationship between the reported believability of the SMS lie participants had been told and its perceived wrongfulness.

Given the pervasive use of SMS a tool to facilitate communication in multiple ways it is important to recognize that it is being used as a medium to communicate deception. Further, that those receiving SMS messages are evaluating the veracity of the message. A logical a next step might be to identify what, if any, methods are being used by recipients to detect the deception in SMS and if they correlate with methods used in other electronic mediums. Future research could focus on how and why those methods are being employed and if they are effective. In addition, the impact of having been deceived in a SMS has on individual’s perceptions of the medium as an effective communication tool should be addressed.

References

Birnholtz, J. P., Guillory, J., Hancock, J. T., & Bazarova, N. N. (2010). “On my way”: Deceptive texting and interpersonal awareness narratives. Proceedings of the Computer-Supported Cooperative Work Conference (CSCW 2010), February 6-10, Savannah, GA

Caspi, A. & Gorsky, P. (2006). Online deception: Prevalence, motivation, and emotion. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 9, 54-59.

Drouin, M., Tobin, E., & Wygant, K. (2014). “Love the Way You Lie”: Sexting deception in romantic relationships. Computers in Human Behavior, 35, 542-547.

French, M., Smith, M. E., Birnholtz, J., & Hancock, J. T. (2015, April). Is This How We (All) Do It?: Butler Lies and Ambiguity Through a Broader Lens. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 4079-4082).

International Telecommunication Union (2010). The World in 2010: ICT facts and figures. Retrieved from http://www.itu.int/ITU-D/ict/material/FactsFigures2010.pdf

Harley, D., Winn, S., Pemberton, S., & Wilcox, P. (2007). Using texting to support students’ transition to university. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 44(3), 229-241.

Jin, B. (2013). Hurtful texting in friendships: Satisfaction buffers the distancing effects of intention. Communication Research Reports, 30(2), 148-156.

Lu, H. (2008). Sensation-seeking, Internet dependency, and online interpersonal deception. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 11, 227-237.

Merkle (2010). The view from the mobile inbox 2010. Retrieved from http://www.merkleinc.com/vfmb/documents/View%20From%20Mobile%20Inbox%202010.pdf

Morrill, T. B., Jones, R. M., & Vaterlaus, J. M. (2013). Motivations for text messaging: gender and age differences among young adults. North American Journal of Psychology, 15(1), 1.

Naquin, C. E., Kurtzberg, T. R., & Belkin, L. Y. (2010). The finer points of lying online: E-mail versus pen and paper. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95, 387-394.

Pettigrew, J. (2009). Text messaging and connectedness within close interpersonal relationship, Marriage & Family Review, 45, 697-716.

Reid, F. J. M. & Reid, D. J. (2010). The expressive and conversational affordance of mobile messaging. Behaviour & Information Technology, 29, 3-22.

Thurlow C. (2003). Generation txt? The sociolinguistics of young people’s text-messaging. Discourse Analysis Online 1. Available at: http://www.shu.ac.uk/daol/articles/v1/n1/a3/thurlow2002003-paper.html.

Wise, M., & Rodriguez, D. (2013). Detecting deceptive communication through computer-mediated technology: Applying interpersonal deception theory to texting behavior. Communication Research Reports, 30(4), 342-346.

Media Psychology Review Journal for Media Psychology

Media Psychology Review Journal for Media Psychology