Chrysalis L. Wright, PhD

University of Central Florida

Tina Ho

University of Central Florida

Elizabeth Raatma

University of Central Florida

Megan Tompkins

University of Central Florida

The current study examined racial comedy and participants’ level of racism and attitudes toward African Americans using an experimental design. It was hypothesized that exposure to disparagement humor would negatively influence viewers’ attitudes regarding African Americans. Additionally, a primary goal of this research was to examine a mediational model between race and exposure to disparagement racial comedy, ethnocentrism, and racism. Participants included 245 male and female college students who were randomly assigned to three experimental conditions where they viewed either (1) positive stereotypical portrayals of African Americans (i.e., racial humor), (2) negative stereotypical portrayals of African Americans (i.e., disparagement racial comedy), or (3) no videos. Participants in each group then completed measures of symbolic racism as well as pro-black and anti-black attitudes and ethnocentrism. Results indicated that participants who were primed with racial humor reported higher levels of anti-black attitudes and ethnocentrism. Participants who were primed with disparagement racial comedy reported higher levels of symbolic racism and pro-black attitudes. Results of the Test of Joint Significance confirmed the mediational model tested in the study in that white participants who viewed racial humor reported higher levels of ethnocentrism, which was associated with higher levels of racism and anti-black attitudes.

Keywords: disparagement humor, racism, priming

- Citation

- Authors

Chrysalis L. Wright, Ph.D. is the Director of the Media & Migration Lab and faculty member in the psychology department at the University of Central Florida. Her research centers around media (broadly defined) and technological influences on developmental processes and behavior. She can be reached at Chrysalis.Wright@ucf.edu.

Tina Ho recently completed her B.S. degree in psychology from the University of Central Florida. Tina was a research assistant in the Media & Migration Lab for four semesters and is currently applying to graduate programs in her field. She can be reached at tinabho@knights.ucf.edu.

Elizabeth Raatma recently completed her B.S. degree in psychology from the University of Central Florida. Elizabeth was a research assistant in the Media & Migration Lab for four semesters. She can be reached at ekraatma@knights.ucf.edu.

Megan Tompkins recently completed her B.S. degree in psychology from the University of Central Florida. Megan was a research assistant in the Media & Migration Lab for three semesters. She can be reached at megantompkins12@knights.ucf.edu.

Author Note:

Chrysalis L. Wright, Department of Psychology, University of Central Florida.

The data presented, the statements made, and the views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Chrysalis L. Wright, Department of Psychology, University of Central Florida, 4000 Central Florida Blvd, Orlando, FL 32816. E-mail: Chrysalis.Wright@ucf.edu.

Introduction

The media that consumers are exposed to can have an undeniable impact on their perception of the world and other people. One of the most enduring and influential genres in media is comedy. Comedy can be used for entertainment, amusement, and laughter, but can also be used as a tool to discuss sociocultural topics, decrease tension between groups, and improve social interactions (Apte, 1987; Green & Linders, 2016; Lefcourt & Martin, 1986; Wyer & Collins, 1992). Whether a topic is acceptable to joke about remains a controversial and subjective matter (Apte, 1987; Barnes, Palmary, & Durrheim, 2001; Goldstein & McGhee, 2013; Green & Linders, 2016). Disparagement humor directed toward African Americans, or humor at the expense of African Americans, who are generally marginalized, as well as humor regarding the stereotypes associated with African Americans (Ford & Ferguson, 2004; Mallet, Ford, & Woodzicka, 2016; O’Connor, Ford, & Banos, 2017) is one of these highly controversial topics.

Television is one of the most popular forms of media (The Nielsen Group, 2015) with consistent, daily viewing starting as early as three years of age and continuing through the lifespan, with exposure time and media-multitasking increasing with age (Hasebrink, 2007; Rideout & Hamel, 2006; Rideout, Roberts, & Foehr, 2005; Scheibe, 2007). This is important considering that studies have shown that television has the power to shift cultural norms, educate consumers, and alter negative stereotypes regarding minority groups (Stamps, 2017). Even so, comedy that is meant to challenge racist ideas may actually strengthen them (Saucier et al., 2018). Furthermore, the influence of racial comedy can serve to both reinforce and wane stereotypes (Green & Linders, 2016).

African Americans in Television

Ever since the 1950’s, sitcoms have played a critical role in American culture and comedy as a whole. After the Civil Rights movement, the socioeconomic and political shifts had both positive and negative impacts on the ways in which African Americans were portrayed and represented on television. In the 1970s and 1980s, African Americans were commonly depicted with negative stereotypes regarding wealth and success. Television sitcoms, such as The Cosby Show and Charlie and Company, aired around the same time and generally depicted storylines that focused on family and daily life situations (Cummings, 1988). Depictions of stereotypical attributes of African Americans in sitcoms have increased since the airing of The Cosby Show (Watts, 2015).

Over the years, there has been research examining the overall impact of racial comedy and disparagement racial comedy involving African Americans within both past and present-day situational comedies. Ford (1997) reported that exposure to negative stereotypes of African Americans in media was associated with consumers reported judgment of African Americans. Mastro and Tropp (2004) analyzed how negative stereotypes of African Americans in sitcoms influenced the beliefs of white consumers. Participants in their study were given a pretest before watching a video clip and then asked to provide evaluations of the African American characters depicted in the sitcom. Results indicated that African American characters were rated less positively when participants viewed negative stereotypical portrayals of African American characters. Additionally, Mastro and Tropp (2004) concluded that consumers who held preexisting high levels of prejudice received a sense of confirmation from viewing stereotypical portrayals of African Americans in media.

While comedic sitcoms can promote a vision of racial equality and equal opportunity (Busselle & Crandall, 2010), disparagement racial comedy with negative portrayals of African Americans can also act to reinforce negative stereotypes that viewers may hold. This is especially true when consumers lack firsthand or direct experiences with members of the African American community (Tan, Fujioka, & Tan, 2000). Studies have demonstrated that consumers are likely to believe that the manner in which African Americans are portrayed on television is accurate and a reflection of reality (Punyanunt-Carter, 2008). Additional studies have concluded that the portrayal of the African American family in comedic family sitcoms, such as The Cosby Show, invoke a sense of enlightened racism among viewers, reinforcing the idea that African Americans do not face any institutionalized obstacles and that perceived inequalities are the result of laziness and ineptitude, which then leads to views in opposition of affirmative action (Crooks, 2014).

Theoretical Perspectives

The current study is grounded in several relatable theoretical perspectives. The prejudiced norm theory (Ford & Ferguson, 2004) proposes that exposure to disparagement racial comedy may increase racist attitudes among consumers and promote prejudiced behaviors. Presenting racism as commonplace or lax, racial humor may inflate the boundaries of acceptable behavior, encourage stereotypical views of racial minorities, and promote prejudicial and biased behaviors. Prejudiced norm theory may help explain why racial comedy may reinforce and strengthen negative stereotypes among consumers (Ford, 1997; Green & Linders, 2016; Saucier et al., 2018). Additionally, the superiority theory highlights the power of comedy to further segregate groups by reinforcing a sense of superiority among members of the in-group, while laughing at outgroup members (Duncan, 1985). Disparaging racial humor creates a social distance between those who initiate the humor and those who are subjects of the humor (Meyer, 2000; Meyers & Williamson, 2001). The superiority theory may help explain how racial comedy can promote ideals of racial equality and equal opportunity (Busselle & Crandall, 2010) while confirming negative stereotypes (Mastro & Tropp, 2004) and invoking enlightened racism (Crooks, 2014) among consumers.

We also theorized that racial humor and disparagement racial comedy can relate to consumers racial views and attitudes through priming. Priming involves a form of stimulation (e.g., disparagement racial comedy) of people’s mental representations of others (e.g., African Americans), occurring outside of mental awareness, that then influences attitudes and behaviors (Eitam & Higgins, 2010; Higgins & Eitam, 2014; Loersch & Payne, 2011; 2014).

The Current Study

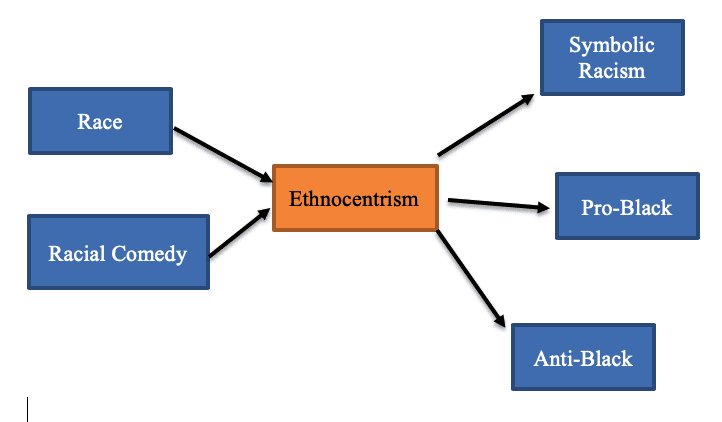

The current study sought to determine if exposure to disparagement racial comedy impacted viewers’ attitudes toward African Americans, particularly symbolic racism (Henry & Sears, 2002; Sears & Henry, 2005) as well as pro-black and anti-black attitudes (Katz & Hass, 1988). Symbolic racism can be considered a coherent belief system combining ideas of: “racial discrimination is no longer a serious obstacle to black’s prospects for a good life; blacks’ continuing disadvantages are due to their own unwillingness to take responsibility for their lives; and that, as a result, black’s continuing anger about their own treatment, their demands for better treatment, and the various kinds of special attention given to them are not justified” (Henry & Sears, 2002, p. 254). Additionally, a primary goal of this research was to examine a mediational model between race and exposure to disparagement racial comedy, ethnocentrism, and racism (see Figure 1). We hypothesized that ethnocentrism, or the disposition where the values, attitudes, and behaviors of one’s ingroup are used as the standard for judging and evaluating another group’s values, attitudes, and behaviors (Neuliep, 2002), can help explain the enlightened racism (Crooks, 2014) that consumers may experience after being exposed to racial humor and disparagement racial comedy.

Figure 1. Hypothesized Mediational Model

The current study utilized an experimental design in which participants were primed with disparagement racial comedy and then assessed to determine their level of ethnocentrism and racist attitudes. It was hypothesized that exposure to disparagement racial comedy would negatively influence viewers attitudes regarding African Americans. It was also hypothesized that racial humor (i.e., positive stereotypical portrayals of African Americans) would increase levels of ethnocentrism among non-African American consumers, which would then lead to higher reported levels of racism and anti-black attitudes.

Method

Participants and procedure

Participants included a total of 245 college students from a large southeastern public research university who were recruited through their undergraduate psychology courses and received class credit for completing the 45-min online questionnaire. The majority of participants were female (n = 148, 53%) and identified as White (n = 128, 45.9%). The mean age of participants was 20.85 years.

Participants were assigned to three experimental conditions in which they were primed with either video clips containing racial humor (i.e., positive stereotypical portrayals of African Americans), disparagement racial comedy (i.e., negative stereotypical portrayals of African Americans), or no video clips. Inter-rater reliability regarding the nature of the videos presented to participants in the current study was assessed using intraclass reliability and was high for the videos examined in the current study (0.93). In an attempt to ensure participants were not aware of the potential primed influence on their attitudes (Higgins, 1996; Loersch & Payne, 2014), assessed via questionnaire, participants were not asked to respond, rate, or evaluate the video clips they were primed with in any way.

Participants in condition 1 (n = 75; 28 males and 47 females; 52% White) viewed racial humor video clips (i.e., positive stereotypical portrayals of African Americans). Video clips were derived from Black Ish (1:59; 2:29), Brooklyn Nine-Nine (0:36; 0:42), and Grown-Ish (2:10). All videos were accessible via YouTube and took 7:56 minutes to view.

Participants in condition 2 (n = 81; 32 males and 49 females; 61.7% White) viewed video clips of disparagement racial comedy (i.e., negative stereotypical portrayals of African Americans). Video clips were derived from Modern Family (1:09), New Girl (2:11), and Black Ish (3:35, 1:06). All videos were accessible via YouTube and took 8:01 minutes to view.

Participants in condition 3 (n = 89; 37 males and 52 females; 43.8% White) did not view any video clips. After viewing the video clips, participants then completed an online questionnaire containing items related to views and attitudes regarding African Americans and ethnocentrism.

Measures

Symbolic Racism. Participants in all conditions completed the Symbolic Racism Scale (Henry & Sears, 2000; Sears & Henry, 2005). This is an 8-item questionnaire that assesses participants’ views regarding symbolic racism. Sample items include “Some say that black leaders have been trying to push too fast. Others feel that they haven’t pushed fast enough. What do you think?” and “Over the past few years, blacks have gotten less than they deserve.” The majority of items were scored on a 4-point Likert scale with 1 being strongly disagree and 4 being strongly agree with four items being reverse coded. Items were summed to derive at a total score that was used in analyses. Higher scores indicated higher rates of symbolic racism. Alpha reliability for the current study was .79.

Pro-Black Attitudes. Participants completed the ten items to assess their pro-black views (Katz & Hass, 1988). Sample items include “Most Blacks are no longer discriminated against” and “This country would be better off if it were more willing to assimilate the good things in Black culture.” Items were scored on a 4-point Likert scale with 1 being strongly disagree and 4 being strongly agree with two items being reverse coded. Items were summed to derive at a total score that was used in analyses. Higher scores indicate more pro-black attitudes. Alpha reliability in the current study was .87.

Anti-Black Attitudes. Participants completed the ten items to assess their pro-black views (Katz & Hass, 1988). Sample items include “On the whole, Black people don’t stress education and training” and “Very few Black people are just looking for a free ride.” Items were scored on a 4-point Likert scale with 1 being strongly disagree and 4 being strongly agree with two items being reverse coded. Items were summed to derive at a total score that was used in analyses. Higher scores indicate more pro-black attitudes. Alpha reliability in the current study was .83.

Ethnocentrism. Participants completed the Ethnocentrism Scale (Neuliep, 2002) to assess how participants viewed their culture compared to other cultures. This is a 22-item questionnaire with items scored on a 4-point Likert scale with 1 being strongly disagree and 4 being strongly agree. Sample items include “Most other cultures are backward compared to my culture” and “My culture should be the role model for other cultures.” Three items were reverse coded. Items were subbed to derive at a total score that was used in analyses. Higher scores indicated higher rates of ethnocentrism. Alpha reliability for the current study was .83.

Demographic questionnaire. Participants were asked four questions related to their age, race (dummy coded as white and non-white), social class, and biological sex.

Results

Preliminary analyses were conducted to assess the reliability of scales, distributional characteristics, intercorrelations of measures, and the extent of missing data. Missing data for the current study were minimal (< 5%), therefore a simple mean substitution method was used (Kline, 2005). This method of handling missing data is preferable to deletion methods as it allows for complete case analyses, does not reduce the statistical power of tests, and takes into consideration the reason for missing data (Twala, 2009). Moreover, this method of data imputation is a good representation of the original data as long as the missing data are less than 20%, which was the case in this study (Downey & King, 1998).

Analyses relevant to the study aims included: (a) descriptive statistics regarding participants views regarding African Americans, (b) intercorrelations of study variables, (c) an analysis of variance to determine if there were significant differences in participants attitudes regarding African Americans based on experimental condition, and (d) a test of joint significance (TJS) to test the mediational model of participant race and exposure to racial comedy influencing levels of ethnocentrism, which in turn, influenced participants reported symbolic racism as well as pro-black and anti-black attitudes.

Participants Attitudes Regarding African Americans

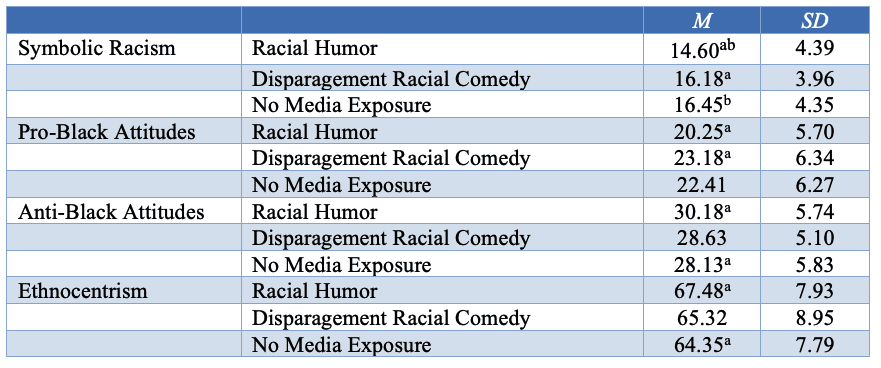

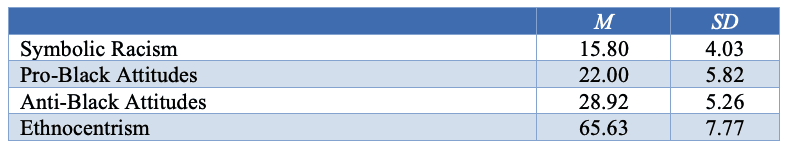

Descriptive statistics for participants’ attitudes regarding African Americans can be found in Table 1. Overall, participants reported high levels of anti-black attitudes (M = 28.92, SD = 5.26). Participants also reported moderate levels of both symbolic racism (M = 15.80, SD = 4.03) and pro-black attitudes (M = 22.00, SD = 5.82). Participants also reported high levels of ethnocentrism (M = 65.63, SD = 7.77).

Table 1. Participants Attitudes Regarding African Americans and Ethnocentrism

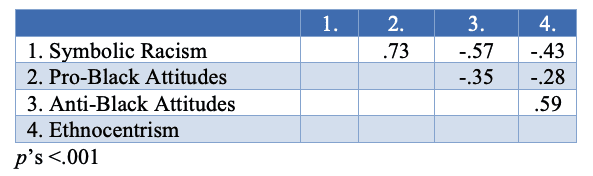

Intercorrelations of Outcome Variables

Intercorrelations of participant views and attitudes regarding African Americans were conducted to determine how the outcome variables were associated with each other. As can be seen in Table 2 all outcome variables were significantly correlated with each other (p = .00 for all correlations).

Table 2. Intercorrelations of Study Variables

Experimental Conditions

An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to determine if there was a significant difference in participants’ views and attitudes regarding African Americans based on experimental condition. Significant differences based on experimental condition were found for symbolic racism, F (2, 242) = 4.38, p = .01, η2 = .04, pro-black attitudes, F (2, 242) = 4.74, p = .01, η2 = .04, anti-black attitudes, F (2, 242) = 2.91, p = .05, η2 = .02, and ethnocentrism, F (2, 242) = 3.02, p = .05, η2 = .02. It should be noted that the effect size of experimental condition for the significant outcome variables was rather small (Field, 2009).

Participants who viewed racial humor (i.e., positive stereotypical portrayals of African Americans), reported higher levels of anti-black attitudes and ethnocentrism. Participants who viewed disparagement racial comedy (i.e., negative stereotypical portrayals of African Americans), reported higher levels of pro-black attitudes. Participants who viewed no media portrayals of African Americans reported higher levels of symbolic racism, followed by those who viewed disparagement racial comedy and then those who viewed racial humor. Descriptive statistics can be found in Table 3.

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics Based on Experimental Condition

Mediational Model

In order to test the hypothesis that participant race and media exposure influenced participants’ views regarding ethnocentrism, which, in turn, influenced participant attitudes and views regarding African Americans regression analyses were conducted. In the current study, the TJS was used to test the mediational model. This is a variation of the method to test mediation established by Kenny and colleagues (Baron & Kenny, 1986; Kenny, Kashy, & Bolger, 1998). The TJS was chosen in the current study considering the criticisms of the normal theory approach utilized by Kenny and colleagues (Mallinckrodt, Abraham, Wei, & Russell, 2006), the unnecessary inclusion of a path from the predictor to the outcome variable in various situations (Frazier, Tix, & Barron, 2004), including when the predictor variable occurs earlier than the outcome variable (Shrout & Bolger, 2002), and the fact that including the path from the predictor to the outcome measure increases the chance of Type II errors in sample sizes smaller than 500 (Frazier et al., 2004; Kenny et al., 1998).

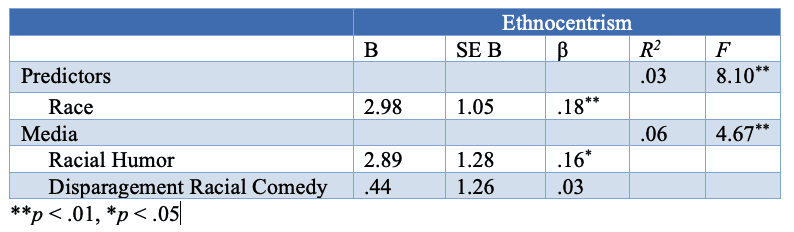

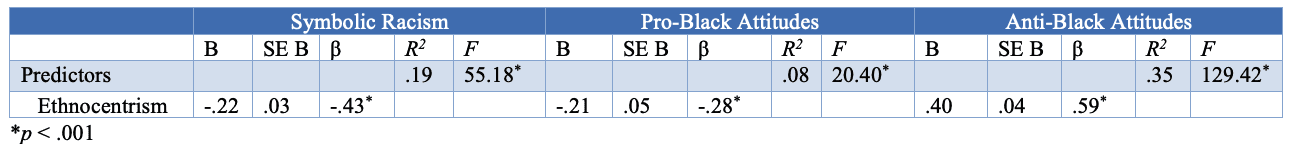

In the TJS, the path from the predictor (race and media exposure) to the mediator (ethnocentrism) and the path from the mediator to the outcome variable (symbolic racism, pro-black attitudes, anti-black attitudes) must be significant in order to conclude a mediational relationship (Cohen & Cohen, 1983; Kenny et al., 1998). The first analysis regressed the dummy coded race variable and exposure to racial humor (i.e., positive stereotypical portrayals of African Americans) or disparagement racial comedy (i.e., negative stereotypical portrayals of African Americans) on ethnocentrism. The second set of analyses regressed ethnocentrism on symbolic racism, pro-black attitudes, and anti-black attitudes. Results can be found in Tables 4 and 5. Overall, results of the TJS analysis indicated a mediated relationship in that participant race and exposure to racial humor and disparagement racial comedy influenced participants’ level of ethnocentrism, which, in turn, predicted participants reported symbolic racism as well as pro-black and anti-black attitudes.

Table 4. Mediational Model: Race and Racial Humor as Predictors of Ethnocentrism

Table 5. Mediational Model: Ethnocentrism as Predictor of Symbolic Racism, Pro-Black Attitudes and Anti-Black Attitudes

Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the relationship between exposure to racial comedy and participants’ attitudes regarding African Americans. We used an experimental approach that primed participants with either racial humor (i.e., positive stereotypical portrayals of African Americans), disparagement racial comedy (i.e., negative stereotypical portrayals of African Americans), or no media portrayals of African Americans. Participants then completed measures of ethnocentrism as well as measures related to attitudes regarding African Americans (i.e., symbolic racism, pro-black attitudes, anti-black attitudes). We hypothesized that exposure to disparagement racial comedy would negatively influence participants’ attitudes regarding African Americans. We also hypothesized that exposure to racial humor (i.e., positive stereotypical portrayals of African Americans) would be related to increased levels of ethnocentrism in non-African American consumers, which would then be related to higher levels of racism and anti-black attitudes. Testing this mediational model (see Figure 1) was a primary goal of this study. Before elaborating on the results, it is important to note that participants reported high levels of anti-black attitudes and ethnocentrism. Participants also reported moderate levels of symbolic racism and pro-black attitudes. Additionally, all outcome variables were significantly correlated with one another.

Media Portrayals of African Americans

Our hypothesis that there would be differences in participants’ attitudes regarding African Americans based on experimental condition was supported by the data. Participants in the current study who were primed with racial humor (i.e., positive stereotypical portrayals of African Americans) reported higher levels of anti-black attitudes and ethnocentrism. Those who were primed with disparagement racial comedy (i.e., negative stereotypical portrayals of African Americans) reported higher levels of symbolic racism and pro-black attitudes. These findings can be explained using the prejudiced norm theory (Ford 1997; Green & Linders, 2016; Saucier et al., 2018) in that racial comedy reinforced and strengthened negative stereotypes regarding African Americans among consumers.

Because of the experimental nature of this design, it can theoretically be determined that viewing specific types of media portrayals of African Americans caused participants attitudes in this area. This supports previous research that has reported similar findings (Crooks, 2014; Ford, 1987; Green & Linders, 2016; Mastro & Tropp, 2004; Saucier et al., 2018). Even so, we exposed participants to video clips they may not regularly view, ultimately creating an artificial exposure that may not reflect their life experiences. This means that their responses may not necessarily reflect their actual views (Bernard & Bernard, 2012; Creswell, 2013; Punch, 2013).

Additionally, three things should be noted regarding our results. First, those who were not exposed to any media portrayals of African Americans reported higher levels of symbolic racism compared to participants in the other experimental conditions. This may indicate that participants in our control group held similar schematic views regarding African Americans but did not have those attitudes brought to consciousness because they were not primed in the current study (see Ramasubramanian, 2007). Second, the effect of media portrayals of African Americans on participants’ attitudes was significant but rather small, ranging from .01 to .04, which is common in experimental designs (Cohen, 1988; Field, 2009; Grabe, Ward, & Hyde, 2008). However, even small effects can have important real-world implications (McCartney & Rosenthal, 2000). Third, the priming effect in this study may have yielded a short-term (i.e., the duration of the study) rather than a long-term effect on participant attitudes (Wentura & Rothermund, 2014). These aspects of our results may indicate that we were unable to control for all extraneous variables (Bernard & Bernard, 2012; Creswell, 2013; Punch, 2013). Even so, our findings support those of previous studies (Crooks, 2014; Ford, 1987; Green & Linders, 2016; Mastro & Tropp, 2004; Saucier et al., 2018) and highlight the importance of further research examining the dosage effect of media priming (Arendt, 2015; Roskos-Ewoldsen et al., 2007).

Mediational Model

In the current study, ethnocentrism was found to mediate the relationship between participants’ race and exposure to stereotypical portrayals of African Americans in racial comedy and participants reported levels of symbolic racism, anti-black attitudes, and pro-black attitudes. These results confirm our hypothesized mediational model (see Figure 1). Results indicated that participant race (white) and exposure to racial humor (i.e., positive stereotypical portrayals of African Americans) was associated with increased levels of ethnocentrism. Increased ethnocentrism was then associated with increased rates of anti-black attitudes but decreased rates of symbolic racism and pro-black attitudes.

In the current study white participants who were exposed to racial humor (but not disparagement racial comedy) reported higher levels of ethnocentrism. This relationship was not present for participants from other racial backgrounds. This is consistent with the findings of previous research in that comedy that is intended to challenge racist views may actually increase those views and reinforce racial stereotypes (Green & Linders, 2016; Saucier et al., 2018). This appears to be the case in the current study. While some previous research has found that exposure to disparagement racial comedy (i.e., negative stereotypical portrayals of African Americans) is associated with racist views among consumers and reinforcement of negative stereotypes (Ford, 1997; Mastro & Tropp, 2004), the results of the current study indicate that racial humor (i.e., positive stereotypical portrayals of African Americans) can have the same effect. It does not matter the manner in which African Americans are portrayed in media. In line with the superiority theory (Duncan, 1985; Meyer, 2000; Meyers & Williamson, 2001) exposure to racial humor (i.e., positive stereotypical portrayals of African Americans) can lead to a sense of enlightened racism among viewers (Crooks, 2014), which is evident in the relationship between participants level of ethnocentrism and reported symbolic racism as well as anti- and pro-black attitudes.

Limitations and Implications for Future Research

While many of the limitations of the current study were discussed previously, there are some additional limitations that merit discussion. The sample used was a college population, representing a distinct group of emerging adults. Also, the study was administered online, which may have interfered with how participants responded to questions. Future research should include a social desirability question in order to help assess the honesty of participants regarding their attitudes toward African Americans. Additionally, as with other forms of media, it is possible that viewers select programming that reflects their personal interests and experiences. Furthermore, instances of disparagement comedic portrayals of African Americans used in the current study were selected to prime participants with both positive stereotypical portrayals and negative stereotypical portrayals. However, it is possible that the interpretations of certain media portrayals may have occurred in the opposite direction than what was intended for some participants. The video clips may also have been interpreted critically before the questionnaire was answered, and this may negate the impact of its effects. Additionally, future research should examine more thoroughly the impact of disparagement racial comedy on consumers’ attitudes regarding African Americans.

References

Apte, M. L. (1987). Ethnic humor versus “sense of humor”. The American Behavioral Scientist, 30(1), 27–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/000276487030003004.

Arendt, F. (2015). Toward a dose-response account of media priming. Communication Research, 42(8), 1089–1115. Doi: 10.1177/0093650213482970 Barnes, B., Palmary, I., & Durrheim, K. (2001). The denial of racism: The role of humor,

personal experience, and self-censorship. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 20(3), 321–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X01020003003.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Bernard, H. R., & Bernard, H. R. (2012). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Busselle, R., & Crandall, H. (2002). Television viewing and perceptions about race differences in socioeconomic success. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 46(2), 265-282.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Cohen, J., & Cohen, P. (1983). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Crooks, R. (2014). Enlightened Racism and The Cosby Show. The Owl, 4(1).

Cummings, M. S. (1988). The changing image of the Black family on television. The Journal of Popular Culture, 22(2), 75-85.

Downey, R. G. & C. King. (1998). Missing data in Likert ratings: A comparison of replacement methods. Journal of General Psychology 125. 175–191.

Duncan, Jack W. (1985). The Superiority Theory of Humor at Work. Small Group Research 42(4): 556–564.

Eitam, B. & E. T. Higgins. (2010). Motivation in mental accessibility: Relevance of a representation (ROAR) as a new framework. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 4. 951–967.

Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS 3rd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Ford, T. E., & Ferguson, M. A. (2004). Social consequences of disparagement humor: A prejudiced norm theory. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 8(79), 79–94. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0801_4.

Ford, T. E. (1997). Effects of stereotypical television portrayals of African-Americans on person perception. Social Psychology Quarterly, 60(3), 266–275. https://doi.org/10.2307/2787086

Frazier, P. A., Tix, A. P., & Barron, K. E. (2004). Testing moderator and mediator effects in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51, 115–134. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.51.1.115

Goldstein, J. H., & McGhee, P. E. (Eds.). (2013). The psychology of humor: Theoretical perspectives and empirical issues. New York, NY: Academic Press.

Grabe, S., Ward, L. M., & Hyde, J. S. (2008). The role of the media in body image concerns among women: A meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychological Bulletin, 134(3), 460-476. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.134.3.460

Green, A. L., & Linders, A. (2016). The impact of comedy on racial and ethnic discourse. Sociological Inquiry, 86, 241-269. https://doi.org/10.1111/soin.12112

Hasebrink, U. (2007). Computer use, international. In J. J. Arnett (ed.), Encyclopedia of children, adolescents, and the media, 207–210. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications

Henry, P. J., & Sears, D. O. (2002). The symbolic racism 2000 scale. Political Psychology, 23, 253-283.

Higgins, E. T. & B. Eitam. (2014). Priming … Shmiming: It’s about knowing when and why stimulated memory representations become active. Social Cognition, 32, 225–242

Higgins, E. T. (1996). Knowledge activation: Accessibility, applicability, and salience. In E. T. Higgins & A. W. Kruglanski (eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles, 133–168. New York: Guilford.

Katz, I., & Hass, R. G. (1988). Racial ambivalence and American value conflict: Correlational and priming studies of dual cognitive structures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55, 893-905.

Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Bolger, N. (1998). Data analysis in social psychology. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (4th ed., pp. 233–265). New York: Oxford University Press.

Kline, R.B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. NY: The Guildford Press.

Lefcourt, H. M., & Martin, R. A. (1986). Humor and life stress: Antidote to adversity. New York: Springer.

Loersch, C. & B. K. Payne. (2014). Situated inference and the what, who, and where of priming. Social Cognition, 32, 137–151.

Loersch, C. & B. K. Payne. (2011). The situated inference model an integrative account of the effects of primes on perception, behavior, and motivation. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(3), 234–252.

Mallet, R. K., Ford, T. E., & Woodzicka, J. A. (2016). What did he mean by that? Humor decreases attributions of sexism and confrontation of sexist jokes. Sex Roles, 75, 272–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0605-2.

Mallinckrodt, B., Abraham, W. T., Wei, M., & Russell, D. W. (2006). Advances in testing the statistical significance of mediation effects. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 372–378. https://doi,org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.3.372

Mastro, DE., & Tropp, L. R. (2004). The effects of interracial contact, attitudes, and stereotypical portrayals on evaluations of black sitcom characters. Communication Research Reports, 21(2), 119–29.

McCartney, K., & Rosenthal, R. (2000). Effect size, practical importance, and social policy for children. Child Development, 71, 173–180. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00131

McConahay, J. B. (1986). Modern racism, ambivalence, and the Modern Racism Scale. In J. F. Dovidio, S. L. Gaertner, J. F. Dovidio, S. L. Gaertner (Eds.), Prejudice, discrimination, and racism (pp. 91-125). San Diego, CA, US: Academic Press.

Meyer, J. (2000). Humor as double-edged sword: Four functions of humor in communication. Communication Theory, 10(3), 310–31.

Myers, K. A. & Williamson, P. (2001). Race talk: The perpetuation of racism through private discourse. Race & Society, 4(1), 3–26.

Neuliep, J. W. (2002). Assessing the reliability and validity of the generalized ethnocentrism scale. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 31(4), 201-215.

O’Connor, E. C., Ford, T. E., & Banos, N. C. (2017). Restoring threatened masculinity: The appeal of sexist and anti-gay humour. Sex Roles. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199- 017-0761-z.

Punch, K. F. (2013). Introduction to social research: Quantitative and qualitative approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Punyanunt-Carter, N. M. (2008). The perceived realism of African American portrayals on television. Howard Journal of Communications, 19(3), 241–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/10646170802218263

Ramasubramanian, S. (2007). Media-based strategies to reduce racial stereotypes activated by news stories. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 84(2), 249–264. doi: 10.1177/107769900708400204

Rideout, V. & E. Hamel. (2006). The media family: Electronic media in the lives of infants, toddlers, preschoolers, and their parents. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation

Rideout, V, D Roberts & U. Foehr. (2005). Generation M: Media in the lives of 8–18-year-olds. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation

Roskos-Ewoldsen, D. R., Klinger, M. R., & Roskos-Ewoldsen, B. R. (2007). Media priming: A meta-analysis. In R. W. Preiss, B. M. Gayle, N. Burrell, M. Allen, & J. Bryant (Eds.), Mass media effects research (pp. 53–80). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum

Saucier, D. A., Strain, M. L., Miller, S. S., O’Dea, C. J., & Till, D. F. (2018). “What do you call a Black guy who flies a plane?”: The effects and understanding of disparagement and confrontational racial humor. Humor: International Journal of Humor Research, 31(1), 105–128. https://doi.org/10.1515/humor-2017-0107

Scheibe, C. (2007). Advertising on children’s programs. In J. J. Arnett (ed.), Encyclopedia of children, adolescents, and the media, 59–60. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Sears, D. O., & Henry, P. J. (2005). Over thirty years later: A contemporary look at symbolic racism and its critics. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 37, 95-150.

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422–445. https://doi.org/10.1037/ 1082-989x.7.4.422

Stamps, D. (2017). The Social Construction of the African American Family on Broadcast Television: A Comparative Analysis of The Cosby Show and Blackish. Howard Journal of Communications, 28(4), 405-420.

Tan, A., Fujioka, Y., & Tan, G. (2000). Television use, stereotypes of African Americans and opinions on affirmative action: An affective model of policy reasoning. Communication Monographs, 67(4), 362–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750009376517

The Nielsen Group. (2015). Nielsen total audience report-Q4 2015. Retrieved from http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/reports/2016/the-total-audience-report-q4-2015.html

Twala, B. (2009). An empirical comparison for techniques for handling incomplete data using decision trees. Applied Artificial Intelligence 23. 373–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/08839510902872223

Watts, C. (2015). The portrayal of African Americans in situation comedies (Doctoral dissertation, Rutgers University-Camden Graduate School).

Wentura, D., & Rothermund, K. (2014). Priming is not priming is not priming. Social Cognition, 32, 47-67.

Wyer, R. S., & Collins, J. E. (1992). A theory of humor elicitation. Psychological Review, 99(4), 663–688. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.99.4.663.

Media Psychology Review Journal for Media Psychology

Media Psychology Review Journal for Media Psychology