Qualitative Research Methods

Research methodology discloses the ways in which we approach problems and look for answers. Our assumptions, interests, and purposes influence our selection of methodology and the mode of application. Debates over methodology, therefore, are debates over assumptions and intent, ideology and perspective. No where is this more apparent than in the debates surrounding the use of quantitative versus qualitative methodologies (Harding, 1986; Keller & Longino, 1996; Kerlinger, 1992).

The debate has been largely played out in the academic arena (Taylor & Bogdan, 1998). Academic resistance to qualitative research illustrates the politics and vested interests embedded in the social sciences and academic institutions. Detractors call qualitative researchers soft scientists whose work is full of bias, entirely personal, and unscientific. Proponents of qualitative methods decry quantitative research as upholding the political status quo and proclaim that the premise of qualitative research challenges the very foundations of the scientific achievements of Western civilization. They hail qualitative research as an answer in the search for knowledge that transcends opinion and personal bias, recognizes individual voices and experience, and promotes the interests of marginalized members of society (Keller & Longino, 1996). In many cases, the conflict has been greater than the need to preserve scholarship or further knowledge (Creswell, 1994; Taylor & Bogdan, 1998).

This paper will review qualitative research methodology with an emphasis on the variations among the traditions of qualitative inquiry and the consequent impact on research design.

What is Qualitative Research?

Qualitative research is a growing field of inquiry that cuts across disciplines and subject matter. It is an elaborate, and often perplexing, grouping of terms, concepts, and assumptions that include the traditions associated with positivism, post-structuralism, and many cultural, critical, and interpretive qualitative research perspectives and methods (Banister, Burman, Parker, Taylor, & Tindall, 1994). Qualitative research, by definition, does not rely on numerical measurements, and depends instead on research that produces descriptive data. It subsumes a range of perspectives, paradigms and methods and within each epistemological theory, qualitative research can mean different things (Creswell, 1998).

Because qualitative research does subsume so many traditions of inquiry, there are possibly as many misconceptions about qualitative research methodology as there are definitions (Denzin & Lincoln, 1994a). There are, however, some consistencies among the varieties of qualitative research.

Parker (1994) calls qualitative research “part of a debate, not a fixed truth” (p. 3). This highlights the nature of qualitative research as an interactive and ongoing process between the researcher and the researched. Banister et al.(1994) define qualitative research as: “an interpretive study of a specified issue or problem in which the researcher is central to the sense that is made (p. 2).”

Denzin & Lincoln (1994b) contribute this more inclusive definition:

Qualitative research is multimethod in focus, involving an interpretive, naturalistic approach to its subject matter. This means that qualitative researchers study things in their actual settings, attempting to make sense of, or interpret, phenomena in terms of the meanings people bring to them. Qualitative research involves the studied use and collection of a variety of empirical materials—case study, personal experience, introspective, life story, interview, observational, historical, interactional, and visual texts—that describe routine and problematic moments and meanings in individuals’ lives. Accordingly, qualitative researchers deploy a wide range of interconnected methods, hoping always to get a better fix on the subject matter at hand (p. 2)

Qualitative versus Quantitative

King (1994) argues that the difference between qualitative and quantitative research is stylistic rather than substantive. The quality of the research, to King, lies in the underlying logic of inference, the quality of the procedure, theoretical basis, goals, and execution. As we know, there is good research that uses both approaches, just as there is bad research.

Both qualitative research and quantitative research seek to understand natural phenomena, provide new knowledge, and permit experience to be replicated in systematic ways. The major difference lies in the goals of each approach. Unlike quantitative research, qualitative research seeks to understand action and experience as a whole and in context. Qualitative research perceives the role of the investigator as integral to the data, not in the traditional view of an objective scientist looking through a telescope.

While quantitative research concentrates on measurements that operationalize constructs, qualitative research uses narrative descriptions, where the words are data and cannot be reduced to numbers. The lack of quantification eliminates the use of statistical analyses for patterns, averages, significance, and probabilities. Instead, the qualitative researcher must use literary and verbal data to reconstruct and understand experience and to identify themes in hopes that a new theory, hypothesis, or relation will be brought to light in ways that extend our understanding. The qualitative investigator is an integrator of the information, giving the data meaning and substance. As such, elimination of investigator bias may not be possible or even desirable.

Qualitative research is in a position to make a unique contribution by elaborating the nature of experience and meaning. Qualitative research has the ability to bring phenomena to life using the explanation of context, multiplicity of voices, and consideration of detail. By bringing experiences to sharp focus, qualitative research can move others to action. Qualitative research projects have triggered policy changes that support more research and better care for AIDS patients (Kazdin, 1998, p. 260), and the advancement of treatment interventions that come from a fuller understanding of lasting distress experienced by victims of childhood abuse (Morrow & Smith, 1995).

Qualitative research does not compete with or replace the value of quantitative research and analysis. Instead, qualitative research can add dimension when reductionist quantitative approaches eliminate the richness, texture, and context. The in-depth study of individuals has made major contributions to clinical psychology (Noblit & Hare, 1988) and the examination of phenomenon in depth permits the generation of hypotheses for further research in both qualitative and quantitative styles (Kazdin, 1998).

Quantitative and qualitative methodologies are framed by different traditions but can be combined to advantage (Denzin & Lincoln, 1994b; Glaser & Strauss, 1967). For example, researchers Campbell and Fisk applied both quantitative and qualitative methods to measure psychological traits. Their aim was to ensure that the variance belonged to the traits being measured, and was not due to methodology (Brewer & Hunter, 1989; cited in Creswell, 1994). Denzin (1978; cited in Janesick, 1994) uses the term triangulation, borrowed from navigation and military strategy, to argue for a combination of data sources and methodologies in the study of the same phenomenon. The concept is based on the assumption that any bias inherent in particular data sources, investigators, and methods would be exposed or neutralized when used in conjunction with other data sources, investigators, and methods (Creswell, 1994). Glaser and Strauss (1967) observe:

There is no fundamental clash between the purposes and capacities of qualitative and quantitative methods or data. What clash there is concerns the primacy of emphasis on verification or generation of theory—to which heated discussion on qualitative versus quantitative data have been linked historically. We believe that each form of data is useful for both verification and generation of theory, whatever the primacy of emphasis… [author’s italics]

In many instances, both forms of data are necessary—not quantitative used to test qualitative, but both used as supplements, as mutual verification, and most important for us, as different forms of data on the same subject, which, when compared, will each generate theory… (p.17-18)

History and Intellectual Heritage

Qualitative research has existed in various forms within fields of social science for almost a century (Tesch, 1990). From the inception, there has been tension between the scholars who advocated objective results that were consistent with the techniques of the natural sciences and those who felt that the phenomenon of human consciousness was too complex to be captured without a different approach (Tierney & Lincoln, 1994). Two philosophical perspectives embodying these distinctions, positivism and phenomenology, have dominated in the social sciences (Taylor & Bogdan, 1998).

From a positivist perspective, a researcher seeks facts or causes of social phenomena independent from the subjective states of individuals. Positivism and the idea of scientific research was spawned by the works of Francis Bacon and Sir Isaac Newton and dates to the 17th century. However, it was two centuries later when “science” emerged to challenge the authority of the Bible and organized religion as the sources of knowledge (Polkinghorne, 1983, p. 16). The burgeoning of the systematic study of human phenomena in history, languages and social institutions, along with the philosophical contributions of Thomas Hobbes, Auguste Comte, and John Stuart Mill, provided a firm philosophical and logical foundation for positivist empiricism as the basis of knowledge (Denzin & Lincoln, 1994a).

The anti-positivist response, a precursor of phenomenology, was inspired by the idealistic and Romantic legacy of philosophers such as Fichte and Schelling in Germany. Although not a unified response, there was general agreement among the anti-positivists that positivism neglected the “unique sphere of meaningful experience that was the defining characteristic of human phenomena and called attention to the sphere of reality that exists because of human beings”(Polkinghorne, 1983, p. 21). The philosophy of Wilhelm Dilthey, who had a prominent voice in the anti-positivist movement, was a harbinger of constructivist thought. He argued that individuals stand in a complex texture of relationships with others. Because individuals do not exist in isolation, he asserted, they cannot be studied outside of the context of their connections to cultural and social life. (Polkinghorne, 1983).

Phenomenology’s influence is great in both philosophy and sociology, where researchers were striving to understand social phenomena from the individual’s own perspective and experience. These philosophical lines of thought have nourished many themes central to qualitative research in postmodern thought, hermeneutics, and dialectics (Kvale, 1992).

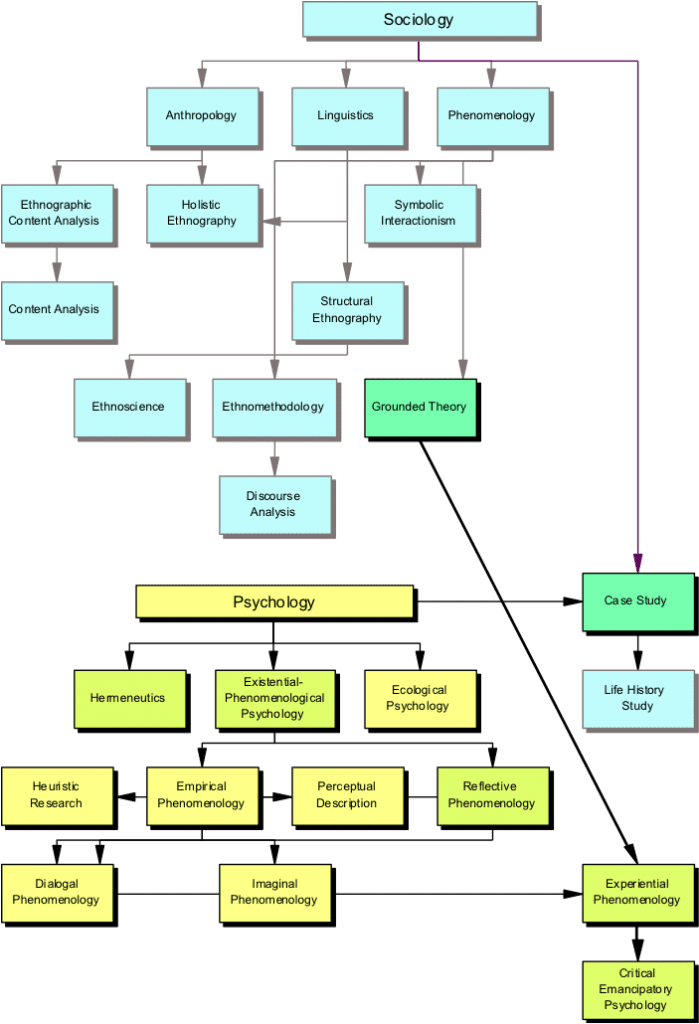

Beginning in sociology, the philosophical evolution of qualitative research has been complex, intertwined with influences across disciplines and methods. Tesch (1990) articulated over twenty philosophical influences in this process, see the following flow chart. It is not surprising that there is so little agreement and clear definition in a field where individual experience is valued over reductionist uniformity.

Philosophical Heritage of Qualitative Research in Sociology and Psychology

(Source: Adapted from Tesch, 1990)

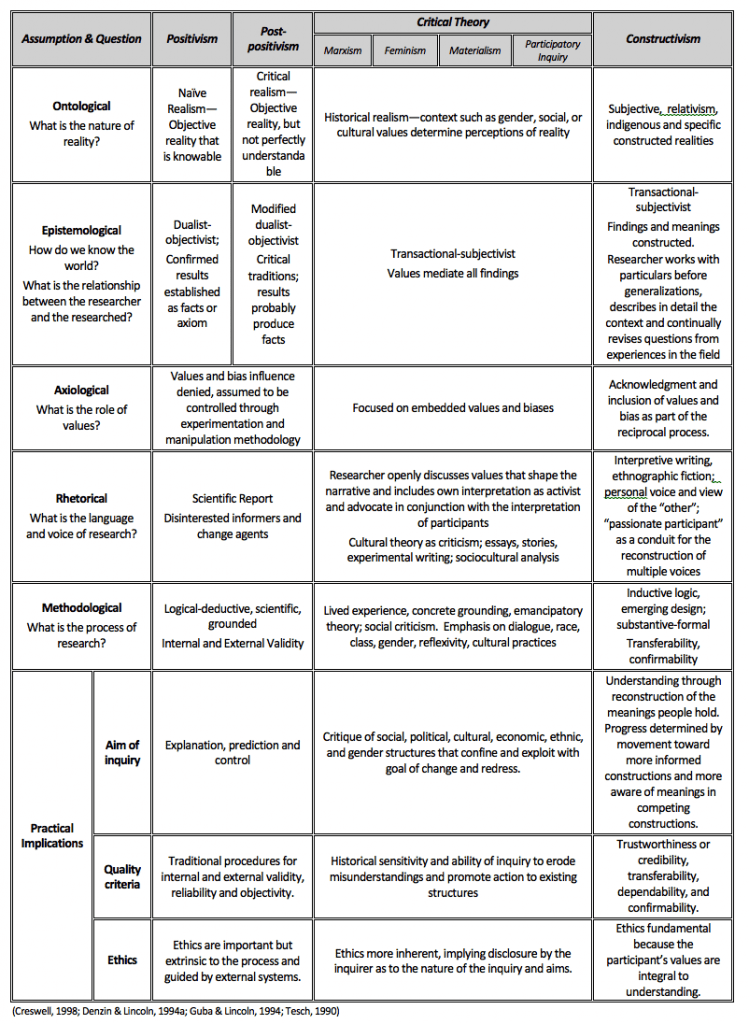

Guba & Lincoln (1994) summarize the field into four major ideological models vying for acceptance among researchers: positivism, postpositivism, critical theory (which includes related ideological positions such as feminist and Marxism), and constructivism. Postmodernism may best be viewed as a family of theories consistent with aspects of critical theory, constructivism and phenomenology (Creswell, 1998). As with the anti-positivists of the late 19th century, postmodernists eschew the glorification of rationality and reason of the 19th century Enlightenment. Critical of the 20th century emphasis on technology, , universals, science, and the positivist, scientific method, postmodern thinking emerged in the humanities of the 1960s and by the 1990s has made a full scale invasion in the social sciences. Postmodern thought centers on the idea that knowledge must be defined within the context of the world today and in the multiples perspectives of race, gender, class, and other groups associations. Postmodernism is characterized by a number of interrelated characteristic and encourages the reading of qualitative narratives as rhetoric and a state of social being (Agger, 1991; in Creswell, 1998) Here is a summarized overview of Guba & Lincoln’s four models:

Overview of Qualitative Traditions

.

Qualitative research, though common in sociology and anthropology, had been applied in a nonsystematic and nonrigorous way and achieved little success at theory generation in the first half of the 20th century (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Quantitative researchers, however, were making considerable progress after World War II in advancing statistical measures, producing accurate evidence, and translating theoretical concepts into testable constructs. The enthusiasm to test unconfirmed theories, relegated qualitative work to preliminary, exploratory work for starting surveys. American sociology was soon awash in the emerging systematic canons and rules of evidence of quantitative analysis, including sampling, reliability, validity, frequency distributions, hypothesis construction, and the parsimonious presentation of data (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Advocates of qualitative data tried to systematize the ways in which they collected, assembled and presented data, using the verification rhetoric of quantitative methodology (Glaser & Strauss, 1967, p. 15). Never the less, interest in qualitative methodology waned at the end of the 1940s (Taylor & Bogdan, 1998).

The end of the Cold War and the deconstruction of the Soviet Union revived nationalist and ethnic claims in almost every part of the world. In this newly decentralized world, cultural pluralism became the new shibboleth. The quandaries once posed by cultural relativism have been replaced by the questions arising out of the alleged certainties of primordial descent (Vidich & Lyman, 1994).

In spite of their history elsewhere, qualitative methods are relatively recent arrivals in psychology. They emerged initially as panoply of alternative approaches to those in the mainstream (Taylor & Bogdan, 1998). As interest in qualitative research increased, acceptance of these methods in applied fields, such as program evaluation, policy research, health research, education, social work, special education, treatment outcome, and organizational research, has grown.

Qualitative research is now emerging as a dominant paradigm, consistent with the heightened social and political sensitivity to cultural, contextual, and relational issues. The editorial boards of scholarly journals, always slow to accept change, are beginning to acknowledge the role that qualitative research plays and usage, once limited to management, education, and nursing applications, is increasingly widespread.

Assumptions in Qualitative Methodology

From its inception, qualitative research has sought to provide a vehicle for interpreting another’s experience. Early qualitative researchers made two assumptions. They believed that competent observers could objectively and clearly report on their observations in the social world and on the experiences of others. Researchers also assumed that an individual is able to report on his or her experiences. By combining their observations with the observations provided by subjects through interviews, life stories, personal experiences, and other documents, qualitative researchers sought to reveal the meaning their subjects brought to their life experiences (Denzin & Lincoln, 1994a).

The advent of the postmodernism and poststructuralism has challenged these assumptions, arguing that there is no “clear window to the inner life of the individual” (Denzin & Lincoln, 1994b, p. 12). They assert that there are no objective observations, only observations socially situated in the worlds of the observed and the observer; no single method can grasp the subtle variation in ongoing human experience. As a consequence, qualitative researchers increasingly use a wide range of interconnected, interpretive methods, always seeking improvements in the understanding of the worlds of experience they study (Guba & Lincoln, 1994).

There are some assumptions, however, that remain fundamental to all qualitative methods. a) The researcher’s framework about the nature of reality reflects his or her history, values, class, race, culture, and ethnic perspective. b) The researcher’s perspective inspires a set of questions that are examined in specific ways. c) The relationship between the researcher and the researched reflects the researcher’s epistemological perspective. d) The examination and interpretation of observations, interviews, and other artifacts enables an emerging process of constructed meaning. (Creswell, 1998; Denzin & Lincoln, 1994b).

Nearly all qualitative researchers now acknowledge that their research contains interpretive elements. Most accept the assumption that reality is mediated by many influences, such as the researcher’s bias, the context of the study, the audience for which the text is prepared, and the theoretical framework. Spindler emphasizes the need for researchers studying their own environments to accept the opposite, “making the familiar strange” to create a subjective distance (cited in Tierney & Lincoln, 1994, p. 111). Although we can never entirely step outside our selves, backing away from the data and phenomena enables us to see meanings we might miss in the context. This is well described by a quote from Margaret Mead, who said, “if a fish were to become an anthropologist, the last thing it would discover would be water” (cited in Tierney & Lincoln, 1994, p. 111).

Methodology

Contrary to what you may have heard, qualitative research designs do exist.” (Miles & Huberman, 1994, p. 16)

Qualitative research has evolved from the time where one went into the field and conducted fieldwork; anthropologists once believe that fieldwork was not something you could train people for, you had to do it (Tierney & Lincoln, 1994, p. 108). Now we recognize that methodological choices imply theoretical assumptions and that these assumptions influence virtually every part of the methodological undertaking. Mary Lee Smith (1987; cited in: Tierney & Lincoln, 1994) argues, for example, that different traditions also have different requirements for reliability and validity. Accordingly, in order to be an adequate judge of qualitative research, we must be aware of the questions of trustworthiness implied by each theoretical school.

Qualitative research is not a singular method, overall design strategy, or philosophical stance, even thought there are attempts to bring coherence to the differences among schools and postures. Tierny & Lincoln (1994) suggest that it is the nature of interpretation to be contradictory and have too many meanings. The process of interpretation connects us with the world, reaches into the gap between objects and our representation of them, and continues as our relationship with the world goes on.

The difference between objects and our representation of them is not unique to psychology; it appears in all sciences. Three aspects describe this disparity: a) indexicality occurs when an explanation is always tied to a particular circumstance and will change as the occasion changes; b) inconcludabilityoccurs when supplementation to meaning causes continued mutation; and c) reflexivity describes the reciprocal influence of the way in which we model a phenomenon and our perception of the way it performs (Banister et al., 1994). These are deadly problems in quantitative research, but opportunities in qualitative inquiry. A qualitative researcher in psychology starts at the gap between the object of the study and the way we represent it; the interpretation generated closes the gap as the researcher connects and exchanges meaning with the participant.

As a set of interpretive practices, qualitative research advocates no single methodology over another. It is used in many separate disciplines and it does not belong to a single discipline (Denzin & Lincoln, 1994b). Qualitative research does not have a set of methods entirely its own. Creswell summarizes traditions into five different traditions or strategies of inquiry based upon their representation in the literature–biography, phenomenology, grounded theory, ethnography, and case studies (Creswell, 1998). Some authors (e.g. Denzin & Lincoln, 1994b; Guba & Lincoln, 1994) present similar summaries, while other authors do not distinguish beyond the theoretical bases, suggesting that theory provides the primary decision structure (Taylor & Bogdan, 1998). Still others do not acknowledge different qualitative models of inquiry at all (Bordens & Abbott, 1996; King et al., 1994).

Within the qualitative tradition, polarized debates arise from time to time demanding practitioners declare allegiance to one school or another (Taylor & Bogdan, 1998). Differences still exit among the various theoretical perspectives today. Taylor & Bogdan (1998) summarize these perspectives around three questions: 1) What is the relationship between the observer and the observed? 2) Whose side are we on? 3) Who cares about the research?

Qualitative researchers differ on the relationship between the researcher and the researched. At one extreme are researchers who share with the positivists a belief that realist exists and can be more or less objectively known by an unbiased researcher. Whyte holds firm to the belief that social and physical facts can be objectively discovered and reported on by a conscientious researcher (Denzin, 1992). At the other end of the spectrum are some postmodernists who believe that objective reality does not exist and that all knowledge is subjective and only subjective (Cole, 1994). For example, Denzin takes the position that there is no difference between fact and fiction; from this perspective ethnography becomes autobiography (Taylor & Bogdan, 1998). The views of most qualitative researchers fall somewhere between these two positions (Taylor & Bogdan, 1998). Within phenomenological, symbolic interactionist, and ethnomethodological perspectives, it is taken for granted that reality is socially constructed.

Kerlinger (1992), in writing the classic, Foundations of Behavior Research, clarified and distinguished between quantitative techniques, such as ex post facto, experimental, and survey designs. His work influenced later thinking about the types of quantitative designs (Creswell, 1994). Creswell (1998) suggests that clarity and comparison are needed in qualitative inquiry, too. Comparisons facilitate understanding and contribute to more rigorous and sophisticated designs (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1997).

Research Traditions

The definitions below are intended to provide an overview of variations in perspective and approach of differing qualitative traditions. They are not intended to be inclusive of the full range of diversity within qualitative research.

Grounded Theory

Grounded theory was conceived as a research methodology for generating theory rather than accepting a priori assumptions. Where quantitative researchers are trained to research and verify facts; qualitative researchers work to generate an explanation (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Glaser & Strauss (1967) submit that this helps to eliminate opportunistic use of theories with dubious fit and working capacity.

Grounded theory is a comprehensive method of data collection, analysis and summarization in which an emergent theory is constructed from, and therefore grounded in, direct experience with the phenomena under study (Richie et al., 1997). Data collection, analysis, and theory construction occur concurrently in a reciprocal relationship (Strauss & Corbin, 1997). Grounded theory puts a high emphasis on “theory as process,” a continuously developing form that is not a perfect product (Glaser & Strauss, 1967, p. 32). There is no formal hypotheses developed for testing. Instead, a grounded theory approach attempts to generate an emergent theory reflective of the subjects’ experiences and voice, from their own phenomenological perspectives.

Grounded theory provides a systematic approach to qualitative subject matter. There are formal guidelines for collecting information, guarding against or minimizing bias, making interpretations, checking on interpretations, and ensuring internal consistency and confirmability of findings.

Richie, Fassinger, Linn, Johnson, Prosser & Robinson (1997) used grounded theory methodology to generate theory in “Persistence, Connection, and Passion: A Qualitative Study of the Career Development of Highly Achieving African American-Black and White Women.” The research team selected a sample of eighteen prominent, highly achieving African American-Black and White women in the United States across eight occupational fields. They collected data in semistructured interviews about the women’s experiences pursuing careers and professional success. Using a twelve member research team, Richie et al. focused numerous discussions on data analysis as well as the possible power differentials among team members. Effort was taken to make sure that each member, no matter when they joined the team, was ensured of an equal voice. This view was promoted due to the belief that multiple perspectives would aid in the ongoing articulation and management of subjectivity in data analysis, which Guba and Lincoln call “peer debriefing.”(1986; cited in Greene, 1994).

Using open coding, the data was coded into approximately 3,000 separate concepts, such as early lack of self-confidence. In open coding the research team creates initial categories of information about the phenomenon of interest. Within each category, the team finds properties or subcategories, and looks for data to show the possibilities of, or dimentionalize (Creswell, 1998), each property on a continuum.

The concepts were abstracted and grouped into 123 categories, such as work attitudes and peer career support. The team used axial coding to determine relationships among the categories that emerged from open coding. In axial coding, the research team assembles the data in new ways using a coding paradigm or logic diagram in which the researchers identify a central phenomenon, explore conditions that influence the phenomenon, specifies strategies or actions that result from the phenomenon, identifies the context and intervening conditions, and delineates the outcomes (Creswell, 1998).

The axial coding was the basis for the regrouping into higher order categories, resulting in fifteen distinguishable key categories, such as wanting to change the world, (Richie et al., 1997, p. 7).

As part of the procedure, Richie et al. (1997) used a number of strategies to increase the reliability and validity of the data. The team trained interviewers and both pretested and revised the interview protocol as suggested by Kerlinger (1992). Internal consistency was enhanced by using more than one judge or analyzer of the data. Citing the work of Marshall & Rossman (1989), Richie et al. (1997) encouraged all team members to offer challenges and alternate explanations to the prevailing assumptions.

Internal validity was proposed to be high since the conclusion of the research was grounded in and emerged directly from the data. The results of the study have face validity because the data generated the results directly and created results credible to both participants and consumers of the research. The work on “validity” of narratives emerging from interpretive studies suggests the importance of “verisimilitude” (Van Maanen, 1998; cited in Miles & Huberman, 1994) and authenticity. Kvale (1996) emphasizes validity as a process of checking, questioning and theorizing, not the establishment of rule-based equivalencies with the “real world.” Kvale (1996) observes:

The complexities of validating qualitative research need not be due to an inherent weakness in qualitative methods, but may on the contrary rest on their extraordinary power to picture and to question the complexity of the social reality investigated. (p. 244)

The authors discuss potential limitations that are factors for consideration in many grounded theory based studies. These include researcher bias in interview protocol and data interpretation, although efforts were taken to account for these possibilities by using a team approach and encouraging continued discussion and arbitration of disagreements and conclusions. Richie et al. (1997) also state that the use of grounded theory has potential for individual differences among participants to dissipate once analytic procedures are set into motion. In the grounded theory approach, discrete concepts are collapsed into increasingly general, abstract categories, which are constrained by the applicability to all participants. Consequently, variant responses and unique experiences may receive scant attention. Finally, sampling restrictions may be present in the study due to geographical considerations, the self-selection of the participants, and the time constraints on high achieving women. The standard for selecting these women may have been skewed by social factors, for example, toward women who enjoyed discussing their lives, or who believe in helping other women, among many possibilities. In addition, the study excluded women who were successful outside the workforce, such as homemakers or volunteers.

Richie et al. (1997) presented their results as a central or core story category consisting of beliefs the women held about them. They suggest that comparing their model with existing vocational literature is one method in which qualitative research can be used to increase the knowledge base of theory and empirical findings. Richie et al. felt their study illustrated many ways in which women’s career development differed from men’s and confirmed the inappropriateness of using career theories based upon sample of White men to White women and people of color.

Biography

A biographical study focuses on one individual and his or her experiences as told to a researcher or found in documents and archival material. From a postmodern or constructivist perspective, all methods are biographical in the sense that they are constructed from the personal histories of the investigator and the subject. Biographies cut across all social science disciplines and takes many different forms, including objective, historical, narrative, institutional, personal, or fictional (Smith, 1994). Denzin defines the biographical method as “studied use and collection of life documents that describe turning-point moments in an individual’s life” (1989; cited in Creswell, 1998, p. 47).

The investigator begins with an objective set of experiences in the subject’s life, noting life course stages and experiences. With a focus on gathering and organizing stories, the researcher explores the meanings of the stories looking for pivotal events and multiple meanings. At the same time, the researcher must be aware of the historical context and larger structures that may contribute to meanings, such as social interactions or cultural issues (Creswell, 1998).

The biography has not been a common form of research in psychology (Smith, 1994). An exception, however, is found in work by Henry Murray. Murray published several works, including the Use of Personal Documents in Psychological Science (1942) and Letters from Jenny (1965.) The Letters are a detailed account that provide a “vivid, troubling, introspective accounts of both her [Jenny’s] life as a working woman and mother and her accompanying mental states.” (Smith, 1994, p. 297).

Phenomenology

A phenomenological study is concerned with reality-constituting interpretive practices and describes the meaning of lived experiences for several individuals about a single phenomenon. Rooted in the philosophy of Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre, and Merle-Ponty (Creswell, 1998; Polkinghorne, 1983), it has been used in psychology, sociology, nursing and health sciences, and education (Tesch, 1990).

Many researchers use participant observation and interviewing as ways of investigating the interpretive practices of individuals (Holstein & Gubrium, 1994). Some investigators, more firmly grounded in the ethnomethodological tradition, argue against the use of any method as a tool that may only serve to produce verifiable findings for a given paradigm (Denzin & Lincoln, 1994b).

The phenomenological approach focuses on the interpretive procedures and practices that give structure and meaning to everyday life. These form the substance and the resources for the inquiry. From this framework, knowledge is local and embedded in the culture and organizational relations. Local culture contains stereotypes and ideologies, implications for gender, race and class, and the understandings about the rules of society that can also inspire critical, feminist, and Marxist theorists (Denzin & Lincoln, 1994b; Kitayama & Markus, 1995; Riger, 1995).

In a phenomenological study, researchers search for the essential or invariant structure that illuminates the underlying meaning of the experiences (Creswell, 1998). Phenomenology emphasizes the intentionality of consciousness that is expressed in both outward appearance and inward consciousness based on images, recollection, and interpretation. In phenomenology, reality is not divided into subjects and objects. Consciousness is always aimed toward an object; consequently the reality of an object is inextricably intertwined with our consciousness of it (Holstein & Gubrium, 1994). Reality only exists within the meaning of the individual’s experience.

Phenomenological data analysis employs the reduction of data, the analysis of specific passages, individual elements of discourse, and patterns, as well as a search for all possible meanings. The investigator attempts to set aside all personal judgments and expectations by bracketing his or her experiences. Bracketing is equivalent to Husserl’s notion of epoche, the suspension of “all judgments about what is real—the ‘natural attitude’—until they are founded on a more certain basis” (Creswell, 1998, p. 52).

In contrast to sociology, phenomenology in field of psychology places more importance on bracketing out prejudgments and developing universal structures. Moustakas (1994; cited in Creswell, 1998) observes that this approach focuses on the meaning of individual rather than group experiences with emphasis on:

…what an experience means for the persons who have had the experience and are able to provide a comprehensive description of it. From the individual descriptions, general or universal meanings are derived, in other words, the essences of structures of the experience. (p. 54)

Worthen & McNeill (Worthen & McNeill, 1996) used a phenomenological approach in their investigation “A Phenomenological Investigation of ‘Good’ Supervision Events.” This study was conducted from the perspective doctoral level clinical supervisees regarding their experiences of supervision events. Worthen & McNeill established a general meaning structure for and identified the salient themes reflective of the experience of good supervision events. They interviewed eight trainees, four men and four women of European-American ethnicity. Although all interviews were conducted and taped by Worthen, a European-American, McNeill, who is of mixed Mexican-American and European-American descent, and an external auditor, participated in and reviewed the interpretive process and results. A research question was developed to guide the investigation: “Please describe for me as completely, clearly, and concretely as you can, an experience during this semester when you felt you received good psychotherapy supervision.” This was followed by prompts for clarification and elaboration as necessary with questions such as, “Can you describe what you felt like?” and “and how did he show that understanding?” (Worthen & McNeill, 1996, p. 28)

Worthen & McNeill went through the following steps, which they adapted from a pattern outlined by Giorgi (1985, 1989; cited in Worthen & McNeill, 1996).

The investigators obtained a sense of the whole from the transcript analysis by listening to the tapes and reading the transcripts several times.

They then identified meaning units by reviewing the transcripts for shifts in meaning. Meaning units represent small, more easily analyzable components. In a phenomenological study, the researcher lists the meaning units and then writes a description of the textures, or textural description, of the experience including literal examples (Creswell, 1998).

Worthen & McNeill then examined the meaning units for relevancy to the research question and discarded those deemed irrelevant.

Integration of the meaning units was achieved by creating a temporal sequence of events to more fully understand the contextual relationship.

The participants’ unanalyzed descriptions of their experiences were then translated into psychologically relevant meanings. Derived meanings were tested against raw interview data by moving back and forth from data to meanings to determine whether they were supported by the data. In the phenomenological process, the researcher reflects on his or her own description and uses “imaginative variation or structural description” to find all possible interpretations and conflicting perspectives by changing the contexts about the phenomenon and constructing a portrayal of how the phenomenon was experienced (Creswell, 1998, p. 150).

The articulated meaning units were then integrated and expressed into a meaningful description of a good supervision experience. These are termed situated meaning, which refers to meaning derived from the context of a specific situation.

From the situated meanings, the descriptions were distilled into a concise form that answered the question: “What is absolutely essential for this experience of good psychotherapy supervision, for which if it were missing this would not represent the experience of good supervision?” (Worthen & McNeill, 1996, p. 30).

The authors discussed the limitations on the generalizability of the results due to the small sample and potential cultural bias of the participants. Worthen and McNeill (1996) summarized the essence of the experience of good supervision through a series of themes–such as sensed inadequacy and sensed supervisor empathy–in the temporal order of appearance.

Ethnography

Denzin & Lincoln (1994) refer to ethnography as:

perhaps the most hotly contested site in qualitative research today. Traditionalists (positivists), postpositivists, and postmodernists compete over the definitions of this field, the criteria that are applied to its texts, and the reflexive place of the researcher in the interpretive process. (p. 203)

An ethnography is a description and interpretation of a cultural or social group or system (Creswell, 1998). The process of ethnographical research typically involves participant observation in which the researcher is immersed in the population of interest. From this vantage, he or she studies the meanings of behavior, language and the interactions of the culture-sharing group (Atkinson & Hammersley, 1994). Culture has been multiply defined, but it commonly refers to the beliefs, values and attitudes that structure the behavior patterns of a specific group of people (Merriam, 1998).

Ethnography had its conception in anthropology and the studies of comparative cultures by scholars such as Mead, Malinowski, and Boas (Creswell, 1998). Atkinson & Hammersley (1994) summarize ethnographical approach based from a sociological vantage. a) There is a strong emphasis on exploring the nature of a social phenomenon. b) Ethnography has a strong tendency to work with unstructured or unanalyzed data. c) The inquiry is limited to a small number of cases or one detailed case. d) The data analysis in an ethnographic inquiry involves explicit interpretation of the meanings and function of behaviors. These can be presented as forms of verbal description and explanations.

Wilson (1997), in “Lost in the Fifties: A Study of Collected Memories,” uses an ethnographic approach to capture the culture and varied meanings of the 1950s through a series of unstructured interviews, artifacts, news media, and popular media. Creswell (1998) provides an example of an ethnographic study by Wolcott (1974; cited by Creswell, 1998) “The Elementary School Principal: Notes from a Field Study.” This project was developed to provide an account of elementary school principalship through a series of interviews and documents.

Case Study

Merriam (1998) observes that, “those with little or no preparation in qualitative research often designate the case study as a sort of catch-all for research that is not a survey or an experiment and is not statistical in nature” (p. 19).

A case study is discriminated from other types of qualitative research by the intensive focus on the description and analysis of a single unit, or bounded system (Creswell, 1998; Merriam, 1998). The object of the inquiry can be an individual, program, event, group, intervention or community, but the topic must deal with specificities not generalities. For example, a nurse may be a case, but his or hernursing lacks the specific boundaries to be called a case (Stake, 1994).

Case researchers seek out what is common and what is distinct about a case. The results, however, typically manifest something unique. Stake (1994) suggests that “uniqueness is likely to be pervasive” (p. 238) and will extend to the case’s nature, historical background, physical setting, economic, political, or aesthetic contexts, sources of information, and reference cases.

The researcher gathers information from all these areas, drawing on multiple sources such as observations, interviews, documents, audio-visual materials, and other media. The type of analysis can be either holistic, examining the entire case, or embedded analysis, which focuses on a single aspect (Yin, 1989; cited inCreswell, 1998). A detailed description is constructed and an interpretive analysis works toward emerging themes. The researcher tells the narrative using a chronology of major events followed by detailed examples, context, and interpretation. When multiple cases are presented, the researcher will typically provide a within-case analysis with a detailed description of each case, and a cross-case analysis tracing the themes throughout (Merriam, 1998).

McRae (McRae, 1994) uses a case study approach in “A Woman’s Story: E Pluribus Unum,” presenting the life of Louisa Rogers Alger. McRae traces the life of Ms. Alger through narratives, correspondence, documents, and interviews. She examines the forces, social and historical context, and experiences that shaped the identity and life of the then 93 year old Ms. Alger against a backdrop of feminist comparison and analysis (McRae, 1994)

Designing a Qualitative Project

Criteria for the Selection of Methodologies and Traditions

Creswell (1994) suggest several factors that need to be considered when selecting a research methodology. These include the researcher’s world view, training and experiences, psychological attributes, the nature of the problem, and the audience.

A researcher needs to be comfortable with the ontological, epistemological, axiological, rhetorical, and methodological assumptions of the qualitative traditions. Training and experiences should include literary writing skills, computer-text analysis skills, and library skills. The qualitative traditions do not provide a specific set of rules and procedures so the researcher must be willing and able to tolerate uncertainty and ambiguity as well as have patience for a potentially lengthy study.

While it is debatable whether certain issues are better for qualitative or quantitative studies (Creswell, 1994; Glaser & Strauss, 1967; King et al., 1994), the nature of the problem is a significant factor. In a qualitative study, the research question needs to be explored because little information exists and the variables are mostly unknown. The investigator focuses on the context that may shape the understanding of the phenomenon being studied, rather than relying on a theoretical base that may not even exist (Creswell, 1994).

Ethical Issues in Qualitative Inquiry

Laura will thoroughly address the topic of ethics in research. I want to mention, however, a couple of issues pertaining directly to qualitative research.

Deception of subjects is both a methodological and a moral issue; it is part of the question of treating people as subjects or as peers. Psychology, due to its reflexive quality, must take a morally and politically sensitive stand. Because the participant and the researcher work together, qualitative research eliminates most concerns of personal reactivity as a threat to procedural integrity, such as demand characteristics, volunteer characteristics, or experimenter effects.

Qualitative inquiry, however, has special characteristics that create ethical questions and dilemmas that do not often arise in experimental or survey research. It is important to be aware and consider each of these issues in the planning stage of the project: a) maintaining anonymity and confidentiality while using the direct works of the respondents to tell the story; b) recognizing the potential intensity and friendships that can be generated from a face to face relationship; c) writing with balance and fairness; and d) separating from the site in ways which preserve and enhance the dignity and respect of the participants and honor the new relationships that have developed (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Josselson & Lieblich, 1996; Kazdin, 1998; Kvale, 1996).

The American Psychological Association (APA) Code of Ethics and the federal government regulations help protect human subjects’ privacy, confidentiality, anonymity and informed consent, but provide few guidelines for the dilemmas which might arise in the course of a qualitative research project (Keith-Spiegel & Koocher, 1995). Qualitative researchers may be subject to abuses or may subject research participants to types of vulnerability uncommon in quantitative research that require foresight and sensitivity.

Format for a Qualitative Research Design

Once the researcher establishes the framework and intent of qualitative research, the study can be designed (Miles & Huberman, 1994). The format of a qualitative study follows many of the traditional steps for presenting a research problem. However, qualitative designs have several unique features.

The researcher frames the study within the assumptions and characteristics of the qualitative approach, including an evolving design, the presentation of multiple realities, the researcher as an instrument of data collection and a focus on the participants’ views. This guides the researcher toward the identification of an appropriate tradition of inquiry and any attendant ethical issues.

The project should begin with a single, well-defined focus or issue that the researcher wants to understand with an overall strategy and rationale. The development of the statement of the problem should include examining the significance of the study. A literature review is used to develop interview questions and concepts, compare the constructs in the literature with those from emerging data, as well as to compare the final results with existing constructs. This facilitates refocusing and refining the research questions and aids in determining the significance and limitations of the study.

The research design includes a description of the specific setting, population or phenomenon and a detail plan of tasks, schedules, and deadlines. The project can be designed as emergent to respond to patterns and data as they occur, but it is critical to have plans and procedures in place (Creswell, 1998; Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Merriam, 1998; Miles & Huberman, 1994). Everything from the gathering and recording of fieldnotes, a plan for data management, data coding and retrieval systems, reflexive logs or journals, to a system of ongoing analysis needs to be thought through and clearly articulated. Computer software is now available for the process of data management, making connections, and interpreting data. There are several varieties of programs with different capabilities. These include word processors (Microsoft Word, WordPerfect), database managers (Access, FilemakerPro, Quattro), and text analysis and theory-building programs (QUALPRO, NUD*IST, AQUAD) (Tesch, 1990) as well as a new generation of text analyzers with visual simulators (Leximancer, Dedoose, etc.). Software is very helpful and powerful; some programs display information in graphical hierarchies, as narratives, as selected word and meaning groups, and even highlight possible patterns (Tesch, 1990). Underlying assumptions shape each program, however, so it is important to be knowledgeable about your research problem and intentions in order to assure a useful software match.

The Quality of Data

Verification is an important issue in qualitative research. Tierney & Lincoln note that “the final report can not be better than the original data” (Tierney & Lincoln, 1994, p. 117). The goal of research is to provide information that has validity. In qualitative research, validity is determined by internal replicability; whether the analysis has some truth or confirmability. This includes coherence of interpretation, agreement among others including the participants, and the consensus that understanding is enhanced as a result of the analysis and that the analysis is salient (Kazdin, 1998, p. 253).

Reliability refers to the methods of studying the data, such as determining in what manner the themes and categories were developed. Reliability focuses on internal consistency. Qualitative research uses many other terms to describe the quality of the data. Trustworthiness refers primarily to credibility and to transferability (Guba & Lincoln, 1994). Credibility describes the appropriateness of the methods and subjects to the goals. Transferability indicates the contextual limitations of the data. Dependabilitypertains to the quality of the conclusions and data evaluations that framed them, Confirmabilityindicates the ability of an outside reviewer to audit the procedures and analysis and reach the same conclusions (Creswell, 1994; Kazdin, 1998)

Richie et al. (1997) discussed various measures taken to improve confirmability and transferability in the study on career development. For example, specific wording was chosen that would minimize response bias due to preconceptions of constructs already in psychological literature. The word handlewas used instead of cope, believe internally replaced references to self-efficacy or attributions. (Richie et al., 1997, p. 5) .

Presentation

In the last few years, new attention has been paid to text creation. This follows logically from the idea that reality is socially constructed. If observed situations are cultural constructions, then so is the presentation of the text. The role of the researcher is defined by the theoretical orientation and that is reflected in the portrayal and interpretation of the data.

A qualitative research report can have many different forms or formats and the reader and writer may enter the narrative from many different perspectives and value points. Clandinin and Connelly (Tierney & Lincoln, 1994) discuss the potential interpretative differences and inconsistencies in the “text” in qualitative research. They note the difference in audience and potential author bias when compiling field text, which is all the materials from the context, compared with compiling research text, which is prepared to address the research community. There is considerably more literary freedom in the presentation of a case study where the researcher tells a narrative, formed and shaped by the story which the researcher is trying to represent. The narrative is enhanced and brought to life by findings, the authorial voice, voices of research respondents, and the original questions more than by reporting conventions.

Conclusion

Qualitative research is designed to describe, interpret and understand human experience. Though qualitative research is frequently defined by how it measures up to the quantitative methods that have played such a central role in psychological research, it has earned its acceptance in the social sciences the hard way—it earned it. At the same time, viewing qualitative research and quantitative research as diametrically opposed devalues them both. There are times when a qualitative researcher will choose to summarize data numerically just as there are times when a quantitative researcher will choose to include descriptive information to facilitate the presentation of statistical data. Qualitative research can open vistas of uncharted territory for further research; quantitative research can add powerful dimensions that come from an assessment of large populations.

A method is the way to a goal (Kvale, 1996), and not the goal itself. The selection of a methodology should not be determined by political or emotional preference, but by the thematic content and purpose of the investigation.

References

Atkinson, P., & Hammersley, M. (1994). Ethnography and Participant Observation. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research (pp. 248-261). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Banister, P., Burman, E., Parker, I., Taylor, M., & Tindall, C. (1994). Qualitative Methods in Psychology: A Research Guide. Philadelphia, PA: Open University Press.

Bordens, K. S., & Abbott, B. B. (1996). Research Design and Methods: A process approach. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing Company.

Cole, P. (1994). Finding A Path Through the Research Maze. The Qualitative Report, 2(1), http://www.nova.edu/sss/QR/BackIssues/QR2-1/cole.html.

Creswell, J. W. (1994). Research Design: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc.

Denzin, N. (1992). Whose Cornerville Is It, Anyway? Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 21(1), 120-132.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994a). Entering the Field of Qualitative Research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research (pp. 1-17). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.). (1994b). Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Greene, J. C. (1994). Qualitative Program Evaluation: Practice and Promise. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research (pp. 530-544). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). Competing Paradigms in Qualitative Research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research (pp. 105-117). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Harding, S. (1986). The Science Question in Feminism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Pres.

Holstein, J. A., & Gubrium, J. F. (1994). Phenomenology, Ethnomethodology, and Interpretive Practice. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research (pp. 262-272). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Janesick, V. J. (1994). The Dance of Qualitative Research Design. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research (pp. 209-219). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Josselson, R., & Lieblich, A. (Eds.). (1996). Ethics and Process: The Narrative Study of Lives. (Vol. IV). Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Kazdin, A. E. (1998). Research Design in Clinical Psychology. (3rd ed.). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Keith-Spiegel, P., & Koocher, G. P. (1995). Ethics in Psychology: Professional Standards and Cases. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Keller, E. F., & Longino, H. E. (1996). Feminism & Science. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Kerlinger, F. N. (1992). Foundations of Behavioral Research. New York: Harcourt Brace College Publishers.

King, G., Keohane, R. O., & Verba, S. (1994). Designing Social Inquiry. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kitayama, S., & Markus, H. R. (1995). Culture and Self: Implications for Internationalizing Psychology. In N. R. Goldberger & J. B. Veroff (Eds.), The Culture and Psychology Reader (pp. 366-383). New York: New York University Press.

Kvale, S. (Ed.). (1992). Psychology and Postmodernism. London: Sage Publications.

Kvale, S. (1996). InterViews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishing.

McRae, J. F. K. (1994). A Woman’s Story: E Pluribus Unum. In R. Josselson & A. Lieblich (Eds.), The Narrative Study of Lives (Vol. II, pp. 195-229). Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis: An Explanded Sourcebook. (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Morrow, S. L., & Smith, M. L. (1995). Constructions of Survival and Coping by Women Who Have Survived. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 42(1), 24-33.

Noblit, G. W., & Hare, R. D. (1988). Meta-Ethnography: Synthesizing Qualitative Studies. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Parker, I. (1994). Qualitative Research. In P. Banister, E. Burman, I. Parker, M. Taylor, & C. Tindall (Eds.), Qualitative Methods in Psychology: A Research Guide (pp. 1-16). Philadelphia, PA: Open University Press.

Polkinghorne, D. (1983). Methodology for the Human Sciences. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Richie, B. S., Fassinger, R. E., Linn, S. G., Johnson, J., Prosser, J., & Robinson, S. (1997). Persistence, Connection, and Passion: A Qualitative Study of the Career Development of Highly Achieving African American-Black and White Women. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 44(2), 133-148.

Riger, S. (1995). Epistemological Debates, Feminist Voices: Science, Social Values, and the Study of Women. In N. R. Goldberger & J. B. Veroff (Eds.), The Culture and Psychology Reader (pp. 139-163). New York: New York University Press.

Smith, L. M. (1994). Biographical Method. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research (pp. 286-305). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Stake, R. E. (1994). Case Studies. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research (pp. 236-247). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1997). Grounded Theory in Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Taylor, S. J., & Bogdan, R. (1998). Introduction to Qualitative Research. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Tesch, R. (1990). Qualitative Research: Analysis Types & Software Tools. New York: The Falmer Press.

Tierney, W. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). Teaching Qualitative Methods in Higher Education. The Review of Higher Education, 17(2), 107-124.

Vidich, A. J., & Lyman, S. M. (1994). Qualitative Methods: Their History in Sociology and Anthropology. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research (pp. 23-43). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Wilson, J. L. (1997). Lost in the Fifties: A Study of Collected Memories. In R. Josselson & A. Lieblich (Eds.), The Narrative Study of Lives (Vol. V, pp. 147-181). Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Worthen, V., & McNeill, B. W. (1996). A Phenomenological Investigation of “Good” Supervision Events.Journal of Counseling Psychology, 43(1), 25-34.

—

Pamela Rutledge, PhD