Person Perception and Enjoyment of Video Game Competition

Daniel M. Shafer, PhD

Baylor University

Abstract:

Abstract:

Friends and strangers were asked to evaluate their opponent’s personality characteristics before and after playing one of four video games in head to head competition. Data was analyzed using a doubly multivariate analysis of variance procedure, along with path analysis. Results suggest that gameplay may influence changes in person perception, but that those changes are contingent on previous relationship. Also, agreeableness of one’s opponent (as well as gender) impacts enjoyment of a competitive video game experience. Results open new research opportunities in the study of video games as social interaction.

Keywords: video games, person perception, friendship, competition, enjoyment

Daniel M. Shafer, Ph.D. is Assistant Professor of Film and Digital Media at Baylor University in Waco, Texas, USA. His research interests include media psychology, video game enjoyment, and morality in entertainment media, as well as effects of new communication technology. His articles have appeared in Mass Communication and Society and Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments. He received his doctorate from Florida State University.

Daniel M. Shafer, Ph.D. is Assistant Professor of Film and Digital Media at Baylor University in Waco, Texas, USA. His research interests include media psychology, video game enjoyment, and morality in entertainment media, as well as effects of new communication technology. His articles have appeared in Mass Communication and Society and Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments. He received his doctorate from Florida State University.

The study of video games and their effects has been underway for nearly 40 years. In the modern era, video games are becoming a popular way to socialize; 65% of gamers report that they often play with others in person (ESA, 2011). First-person shooter (FPS), fighting, sports, and strategy/puzzle games consistently rank high on lists of current popular genres (ESA, 2011; Vorderer, Bryant, Pieper, & Weber, 2006), indicating that a wide range of content is appealing to players of varying characteristics.

The present study joins those focused on the effects and enjoyment of games played as a social activity. The unique problem the present study seeks to investigate is how relationship of the opponents (whether they are friends or strangers) may impact perceptions of the opponent’s personality through the experience of playing a competitive video game. Additionally, this study investigates the impact of those personality judgments on enjoyment of the gaming experience.

Conceptual Framework

Competition and social interaction are two of the most important gratifications players obtain when they play video games (Sherry, Greenberg, Lucas, & Lachlan, 2006). Video games provide an ideal forum for proving who in a social group has the best skills, can think quickly, and react swiftly. Video game competition is similar to that of sports in that higher status is gained for the dominating player (Sherry et al., 2006). As social interaction, video games are often used “to interact with friends and learn about the personalities of others” (Sherry, et al., 2006 p. 218), ostensibly, strangers. Humans have used video games to connect with one another since the days when arcades were popular (Williams, 2006). One question that grows from these facts and assertions is – what effect does interacting with friends and strangers have in the context of playing video games? Furthermore, how do players of video games perceive one another’s personalities, or, how does person perception work in the context of video games?

Are video games different from real-life interaction?

First, it is important to realize that video games are both similar to and different from real-life interaction. The competition found in playing a video game against another person is similar to that of a sports competition (Sherry et al., 2006). Where video games differ is their non-reliance on physical prowess for a player to be successful. Video games offer a platform for competition that, in many ways, equalizes the playing field. Instead, reaction time and quick thinking are the more salient attributes, rather than strength, size, or physical speed (Sherry et al., 2006). Gender, race, weight, and height are virtually irrelevant in the context of a video game competition (Williams, 2006; Sherry et al., 2006).

Person perception. “We look at a person and immediately a certain impression of his character forms itself in us. A glance, a few spoken words are sufficient to tell us a story about a highly complex matter” (Asch, 1946 p. 258). Individuals form impressions of other’s personalities quickly upon coming into contact with them. Scholars (e.g. Hays, 1958) assert that first impressions and snap judgments are made about others with little known information. Hays (1958) argues that techniques for judgment of others build over time. Exline (1963) notes that simple observation of another’s behavior results in judgments about their personality. Once we interact further with the individual in question, our perception of their personality is likely to change based on further exposure to their behavior or revelation of more individuating information (Chan & Mendelsohn, 2010; Taft, 1966).

Therefore, when a stranger is encountered, the arguments of Asch (1946), Hays (1958), and Exline (1963) assert that a quick initial assessment of personality is made. As the interaction continues, that personality judgment is refined based on observed behavior, according to Chan and Mendelson (2010) and Taft (1966). One issue the present study seeks to investigate is how this process of personality judgment develops over the course of participating in a video game competition situation.

Sherry and colleagues (2006) also note that video games offer a good way to interact with friends. Friends are able to make accurate judgments of their counterpart’s personality based on their own self-reports (Funder & Colvin, 1988; Taft, 1966). As such, individuals who have previous friendships with those they interact with should already have accurate knowledge about the other’s personality which would be stable over time (Funder & Colvin, 1988). In contrast to that expectation, individuals who are just meeting for the first time should have their judgments of their counterpart change over time as new information is gathered. Williams and Clippinger (2002) found that participants were less aggressive when playing with another human being versus playing against the computer. The authors suggest, based on Game Theory and other social facilitation theories, that players may have behaved in line with common social norms because they knew they would be evaluated by their opponent, who was a stranger (Williams & Clippinger, 2002). Opponents engaged in friendly conversation during the game, essentially putting their best foot forward in the social situation. Based on this reasoning, it is predicted that:

H1: Strangers’ perceptions of their opponents’ personality will be significantly different over time.

H2: Friends’ perceptions of their opponents’ personality will be stable over time.

Person perception and enjoyment. People would not spend money and time on video games if they were not enjoyable. By the same token, individuals would not play with each other if they found the experience to be without entertainment value. For many teens, gaming is an inherently social activity, with 65% reporting that they play with other physically present people (Lenhart, Kahne, Middaugh, Macgill, Evans & Vitak, 2008). Despite the tendency for individuals to enjoy playing together, scholars have asserted that competition harms interpersonal relationships (Foster, 1984). Competition implies trying to take (the joy of winning) from someone in order to benefit one’s self (i.e., win; Charlesworth, 1996). However, Schneider, Woodburn, Toro and Udvari (2005) found that engagement in competition and non-hostile social comparison actually enhances friendships and can lead individuals to become closer friends. However, those individuals who are hyper-competitive may not see their friendships enhanced by competitive game play. Overall however, competition was found to benefit friendships (Schneider et al., 2005). Additionally, Jones (2001) contends that friendship plays a crucial role in sports competitions, to which video game competition can be compared.

Despite these insights as to how relationships can be impacted by video game competition, no published literature to date has investigated the possible impact of changes in person perception on enjoyment of playing video games. It is simply unknown how the experience of playing video games will change perceptions of others, or if those perceptions will impact the enjoyment of the experience. If the player sees their opponent, for example, as more agreeable or conscientious, it makes sense that the experience would be more enjoyable; but there is no empirical data to support this speculation. Therefore, the following research question is posed:

RQ1: How will changes in person perception impact enjoyment of the video game competition?

Covariates. Several covariates have been found to have an impact on enjoyment in the context of video games. Most relevant to the present study is gender. Differences between men and women on genre preferences, tendency to play, and other factors have been well documented. There is empirical evidence that many video games, especially those featuring violence, are targeted at male consumers (Smith, 2006). Although the ESA (2011) reports that the number of females who play games is on the rise, the majority of reported gamers are men. Numerous studies published over the past three decades report that men like and play games more than women (e.g., Kaplan, 1983; Wright et al., 2001). Therefore, gender will be included in the analysis of predictors of enjoyment as a covariate.

Method

The present study followed a pseudo- experimental pretest-posttest design with a college student sample. The study is pseudo-experimental because participants were not randomly assigned to play with friends or strangers. To randomly select which participants would play with friends and which would play with strangers is impractical at best because there is no guarantee that participants assigned to the friend condition would be willing and able to recruit a friend who would be available for the study at testing times. Therefore it was determined that the pseudo-experimental design was appropriate for the present study.

Participants

Data were collected from 126 students recruited from various communication, film, and computer science courses at a research university in the southern-central U.S. They were offered course or extra credit for their participation (research participation was one option among several opportunities for credit). Data collection was conducted for four weeks. The first two weeks, participants were only allowed to sign up for sessions with a friend; either a friend in class or a friend that they would recruit. In the second two weeks of the study, participants were told to sign up as individuals, and that the researcher would pair them with an opponent. This recruitment technique resulted in two groups: “friends” (n = 56) and “strangers” (n = 70). This final sample of 126 participants was 55.4% male, 44.6% female; and participants ranged in age from 18-34with an average age of 22.2 years (SD = 3.81).

Stimulus Materials

Four games, Tiger Woods PGA Tour 11, Lumines Live, HALO: Reach and Dead or Alive 4 served as stimulus material. Tiger Woods PGA Tour 11 (Electronic Arts, 2010) is a golf simulation game which requires players to compete for the lowest score in a three-hole round of golf. Play alternated between players, and rounds lasted 10 – 15 minutes.

Lumines Live (Atari, 2009) is a Tetris – style puzzle game. It requires players to build blocks of color which disappear, resulting in points. As one player does better than another, the losing player’s screen shrinks, narrowing their options for block building. The first player to win two out of three matches was deemed the winner. Matches lasted 10-15 minutes.

HALO: Reach (Microsoft, 2010) is a space-based first-person shooter video game. Its death match mode requires players to fight until the opponent is “dead”. The player with the most kills won the game. Players played one match. Total play time was 10 – 15 minutes.

Dead or Alive 4 (Tecmo, 2005) is a Mortal Kombat-style martial arts fighting game. Players compete in a martial arts battle in an arena-style stage. Players competed in a best of three round which lasted 10 – 15 minutes. All games were played on the Xbox 360 system.

It is no doubt obvious that these games are vastly different in their content and mechanics. It is often preferred by many researchers in video game effects research to use a single game, or, if different conditions are called for, to use games that are as similar as possible (Simo, Inger, Kivikangas & Ravaja, 2012). This approach is beneficial because it highlights the elements that are hypothesized to contribute to the dependent variable and controls for other varying elements of game play. In the present study, however, a variety of games was chosen for several reasons. First, the games used in the present study all offer a multiplayer mode that can be played by at least two people in a head-to-head, offline situation. With this criterion met, it was determined that the games were “identical in the relevant aspects to the dependent variable” (Simo, et al., 2012 p. 4), given that a major dependent variable was player evaluations of their opponents via head-to-head video game competition. Given the variety of games available to players when they engage in competitive video game play, it seems reasonable to gather data on a variety of games, rather than limiting the results by testing only a single game or genre.

Procedure

Participants arrived in the video game lab and were seated in front of a multimedia station with a 32” HD monitor displaying the online questionnaire. Because two participants were seated at each computer/gaming station, one participant completed the questionnaire online, while their opponent completed it on paper. Each session lasted 40-50 minutes.

Measures

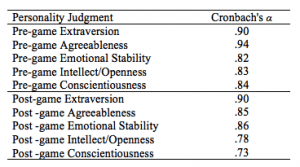

Changes in person perception were assessed using a shortened version of Goldberg’s big-five marker scale (Saucier, 1994). The 40-item questionnaire measures the five personality traits of extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and intellect/openness. The shortened big-five questionnaire is traditionally a self-report measure, but in the present study it was used as an informant report measure. Individual items were answered on a scale ranging from -4 (Extremely Inaccurate) to 4 (Extremely Accurate). See Table 1 for Cronbach’s α levels for each pre- and post-game personality rating.

Table 1: Pre-game and Post-game Personality Judgment Scale Alphas

Enjoyment was measured using a 12-item scale adapted from the measures used in previous studies (e.g., Author, 2012; Shafer et al., 2011). The enjoyment scale asks participants to evaluate their game play experience based on several items. Two sample items are: “the game made me feel good” and “I enjoyed the game”. Answers are given on a continuum from 0 (negative) – 10 (positive). The scale was internally consistent, Cronbach’s α = .89. Scores ranged from 0.67 to 9.33 (M = 5.59, SD = 1.82).

Relationship was assessed using a single item: “Please mark the statement that best characterizes your relationship with your opponent”, with the response categories “I’ve never they met this person”, “I am somewhat acquainted with this person”, and “I have a close or friendly relationship with this person”. Just over 44% of participants reported that they had a close, friendly relationship with their opponent. There were no participants who indicated they were merely acquainted with their opponent (as expected given the recruiting method). The remainder reported that they had never met their opponent before. Therefore, participants were designated “friends” (n = 56, 44.4%) or “strangers” (n = 70, 55.6%).

Gender was simply assessed by asking participants to choose “male” (coded 1) or “female” (coded -1) in response to the question “What is your gender?”

Results

Hypothesis Testing and Research Question Inquiry

Hypothesis 1 predicted that strangers’ personality judgments would change significantly after playing a competitive video game, while H2 predicted that friends’ personality judgments of each other would not change significantly. Research Question 1 inquired as to how changes in personality judgments would impact enjoyment of the game.

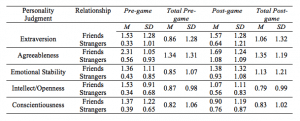

Hypotheses 1 and 2 were tested with a doubly-multivariate repeated measures analysis of co-variance (ANCOVA). The analysis included (a) pre-game and (b) post-game Big Five personality ratings of opponents as the within-subjects variables, and relationship was the between-subjects factor: (a) friends, and (b) strangers. Gender was entered as the covariate. Means and standard deviations for each of the pre- and post-game Big Five personality variables are shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Means & SDs of Big Five Ratings by Relationship; Pre- and Post-Game

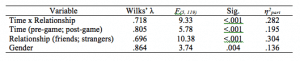

The analysis showed a significant Time x Relationship interaction which accounted for just over 28% of the variance, and a significant main effect for Time which accounted for just under 20% of the variance. A significant main effect for Relationship (30% of the variance), and a main effect of the gender covariate (14% of the variance) were also found. The values for the multivariate F tests are shown in Table 3.

Table 3: Multivariate F Tests: Main & Interaction Effects

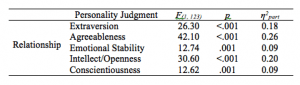

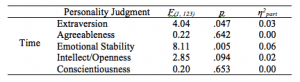

In order to enable a more precise description of the effects of the significant independent variables, follow-up repeated measures multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVAs) were conducted on each personality judgment score. For the within-subjects variable of time (pre-game and post-game ratings), significant differences were found in two of the five personality rating variables. Only Extraversion and Emotional Stability significantly increased after playing a competitive video game (across relationship groups; see Table 4). Because of a violation of the assumption of sphericity, values shown use the Greenhouse-Geisser corrected degrees of freedom.

Table 4: Time MANOVA Results

Relationship, on the other hand, showed significant differences on each personality judgment, regardless of Time. Results of the MANOVAs for Time are listed in Table 5. On all five personality judgment variables, participants who were friends averaged significantly higher ratings of their opponents than those participants who were strangers.

Relationship, on the other hand, showed significant differences on each personality judgment, regardless of Time. Results of the MANOVAs for Time are listed in Table 5. On all five personality judgment variables, participants who were friends averaged significantly higher ratings of their opponents than those participants who were strangers.

Table 5: Relationship MANOVA Results

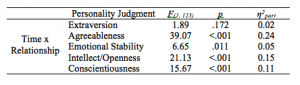

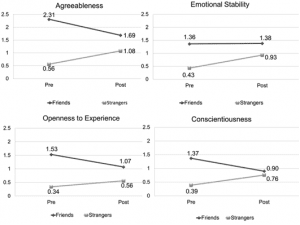

Four of five within-subjects personality rating variables showed significant Time x Relationship interaction effects; Extraversion was the lone exception. Table 6 summarizes these results. The interaction effect describes a pattern of results in which friends’ personality ratings of their opponents significantly dropped from Time 1 to Time 2 on 4 of 5 personality variables. Based on these results, H1 is not supported. Friends’ personality judgments did not remain stable over time; rather, friends judged each other as less agreeable, less emotionally stable, less conscientious, and less open to experience. For strangers, however, personality ratings of opponents increased significantly on all variables. Therefore, H2 is supported.

Table 6: Time x Relationship Interaction MANOVA Results

It is interesting to note, when observing the mean scores for each group at each time; that friends’ pre-game scores were significantly higher than strangers’. Then, despite friends’ ratings dropping significantly and strangers’ ratings increasing significantly, friends’ post-game scores remained higher than strangers’ (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Interaction Effects

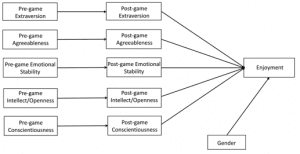

Research question 1, which asked how changes in person perception would impact enjoyment of the video game competition, was investigated using path analysis. A path model was designed which included pre-game and post-game measures of personality judgments, enjoyment, and gender (as a covariate; see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Hypothesized Path Model Investigating RQ1

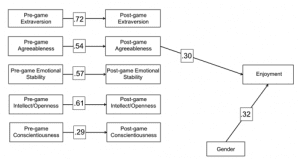

The test of the model, as shown, indicated an adequately-fitting model, χ2 (6, N = 126) = 7.76, p = .260, RMSEA = 0.072; AGFI = .84; NNFI = .96. The model indicated non-significant paths from post-game extraversion, emotional stability, and openness to enjoyment. Agreeableness and Conscientiousness, along with Gender, significantly predicted Enjoyment in the model. The model was re-specified with the non-significant paths deleted. Model fit increased slightly, and the path from Conscientiousness to Enjoyment became non-significant. The deletion of the path between non-significant path between Conscientiousness and Enjoyment resulted in a parsimonious model with improved fit, χ2 (34, N = 126) = 53.30, p = .019, RMSEA = 0.069; AGFI = .85; NNFI = .97 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: RQ1 Path Model Results

For the sake of readability, the significant error co-variances among all pre-game personality variables and also among all post-game personality variables are not shown; likewise the error covariances between gender and the pre-game personality variables are not shown (the model with all covariances shown is available from the author). The model shows that only agreeableness of one’s opponent had a significant impact on enjoyment. Gender was a significant covariate, which indicates that men enjoyed the game competition more than women.

Discussion

The present study pitted friends and strangers against one another in a video game competition. Based on work by Asch (1946), Hays (1958), and Exline (1963), players were asked to make judgments about their opponents’ personality attributes upon meeting their opponent, and again after gathering more information through playing the game (Chan & Mendelsohn, 2010; Taft, 1966). As predicted in H1, players who did not know their opponent reported significant changes in personality judgments before and after playing the game. However, friends also saw changes in personality judgments, contrary to H2, which predicted that their judgments would be stable over time.

The measure used for judgment of personality asks raters to make judgments based on how much the target matches several adjectives that are either positive or negative in valence (Saucier, 1994). The negatively-valenced variables are then recoded so that scores represent how much of that factor is present for the calculation of the average score on the factor. Therefore, scores on the personality judgment variables can be thought in terms of positive and negative judgments about the target individual. Given that higher scores represent more positive judgments and lower scores more negative judgments, the results can be generalized to indicate that friends judged each other significantly more favorably than strangers on the pre-game measures. Then, after the game, friends showed significant decreases in 4 of the 5 variables (all but extraversion). Strangers, on the other hand, judged each other quite unfavorably (ostensibly due to a lack of knowledge of the other person) on the pre-game measure, but significantly more favorably on the post-game measure taken after individuating information was able to be gathered. Still, as favorable as strangers’ post-game judgments of their opponents were, they failed to surpass the level of friends’, despite friends’ post-game judgments being significantly less favorable than the pre-game scores.

One explanation for this finding may be found in Abraham Tesser’s work on social comparison and self-evaluation (Tesser, 2001; Tesser, 1988; Tesser, Millar & Moore, 1988). Tesser’s self-evaluation maintenance model of social behavior (Tesser, 1988; Tesser, et al., 1988) makes the assumption that relationship has a significant impact on self-evaluation and that persons act in a way that maintains or enhances their own positive opinion of themselves. An important concept in Tesser’s theory is that of relevant and irrelevant tasks or activities. Persons react more or less positively and concurrently evaluate themselves more or less positively based on the relevance of the task. A relevant task is one that ostensibly measures the quality of one’s attributes (e.g., intelligence, perception, skill), Irrelevant tasks, such as a game with no value attached, have little consequence to one’s self-worth (Tesser, 1988). Tesser’s (1988) model predicts that, in the context of a task irrelevant to the individual’s self concept, being outperformed by a friend would result in positive self-evaluation as the individual basks in the reflected glory of their friend’s success. In a relevant task, however, the individual’s self concept may suffer by being outperformed by a friend. Furthermore, and perhaps most salient to the present study, Tesser (1988) argues that, when outperformed on a relevant task, individuals may project their own negative evaluations onto their friends. This argument may stand as a partial explanation for the present findings. Friends who evaluated each other as less agreeable, less open to experience, less conscientious, and less emotionally stable may have been projecting their negative emotions onto their opponent, resulting in a less favorable judgment. However, in the absence of more specific prior research on the phenomenon of person perception during video game competitions; such a conclusion is hypothetical. Further research that specifically tests for task relevance and projection of evaluations is necessary.

Another explanation is that all third-variable explanations may not have been accounted forw. For instance, arousal could easily heighten both positive and negative emotions associated with the competitive situation. Games are certainly capable of producing high levels of arousal (Anderson & Bushman, 2001; Fleming & Rickwood, 2001; Ivory & Kalyanaraman, 2007). Typically, in studies that measure arousal, aggressive cognitions and/or hostility is also measured, and is found to be significantly predicted by physiological arousal. One recent study (Shafer, 2012) found that players in PvP (player vs. player) situations (such as in the present study) experienced higher levels of state hostility (a negative, unfavorable reaction) than their counterparts in a PvE situation (this effect was enhanced by losing the game). However, arousal and hostility were not tested in the present study; future research on arousal, hostility, and personality judgments could investigate this speculated relationship.

In the investigation of RQ1, agreeableness emerged as a significant predictor of enjoyment. The more agreeable one’s opponent, the more enjoyable the gaming experience. This finding stands to reason. Agreeable people are more effective at coping with emotions experienced during conflict (Jensen-Campbell & Graziano, 2001). Furthermore, those high in agreeableness are better able to develop affable relationships (Graziano & Eisenberg, 1997). Being agreeable means that one is “cooperative, considerate, empathic, generous, polite, and kind” (Caspi, Roberts, & Shiner, 2005 p. 459). Prosocial tendencies represent the extreme positive outcome of being agreeable (Caspi et al., 2005). As such, it is unsurprising that those players who rated their opponents as agreeable also enjoyed the game experience. It would seem that the results indicate playing with a considerate and generous person, despite competing with them, is enjoyable, and playing with disagreeable individuals who are cynical, rude, and aggressive (Caspi et al., 2005) would be less enjoyable.

Limitations

Besides the limitations already noted (a need to measure task relevance, emotional projection, and arousal), one chief limitation of the study is the use of a student sample. Certainly the sample obtained in the present study does not represent the general population, or even necessarily the population of video game players. However, other recent video game effects studies (e.g., Skalski & Whitbred, 2010; Shafer, Carbonara & Popova, 2011) have used student samples effectively. As Basil (1996) points out, student samples often introduce less error into research than a representative sample. Another limitation, the diversity of the games under study, has been explained an addressed in an earlier section.

Conclusion

There is a great deal left to discover with regard to how video games impact person perception and how they operate as a social activity. What can be concluded, however, is that playing various kinds of games with strangers seems to result in positive evaluations of opponents; indicating that video games may be a useful vehicle for facilitating initial social interaction between peers. Video games are certainly not the only way to do so, but they do provide a unique context for socialization and competition, because skill at video games is not dependent on physical attributes such as height, strength, speed or gender. Being male or female also has little to no bearing on ones’ video game prowess, thus providing a platform for equitable competition (barring differences in experience, of course).

For friends, judgment became less favorable after gameplay. A possible explanation was offered, but what can be gleaned from these results is that friends tended to judge each other less favorably after the game, while strangers judged their opponents more favorably. Whether this more negative evaluation was sustained past the time of the study is unknown.

Across relationship groups, agreeableness emerged as a predictor of game enjoyment; a finding that sheds light on the nature of video game competition. At least for the players in the present study, showing agreeable attitudes such as kindness, empathy, politeness and good sportsmanship was appreciated by opponents despite the competitive nature of the gameplay situation. Even when an opponent is attempting to deprive us of our goal of victory, their attitude and how they approach the situation can make a significant difference in the enjoyableness of the experience.

References

Anderson, C. A., & Bushman, B. J. (2001). Effects of violent video games on aggressive behavior, aggressive cognition, aggressive affect, physiological arousal, and prosocial behavior: A meta-analytic review of the scientific literature. Psychological Science, 12(5), 353–359. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00366

Asch, S. E. (1946). Forming impressions of personality. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 41 (3). 258 – 290.

Atari (2009). Lumines Live!

. in Qubed, Q Entertainment.

Basil, M. D. (1996). The use of student samples in communication research. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 40, 431-440.

Caspi, A., Roberts, B. W., & Shiner, R. L. (2005). Personality development: Stability and change. Annual Review of Psychology 56, 453-484.

Chan, W., & Mendelsohn, G. A. (2010). Disentangling stereotype and person effects: Do social stereotypes bias observer judgment of personality? Journal of Research in Personality, 44(2), 251-257.

Charlesworth, W. R. (1996). Co-operation and competition: Contributions to an evolutionary and developmental model. International Journal of Behavioural Development, 19, 25-39.

ESA (2011). 2011 sales, demographic and usage data: Essential facts about the computer and video game industry. Retrieved 6-13-2011 from http://www.theesa.com/facts/pdfs/ ESA_EF_2011.pdf

Electronic Arts (2010). Tiger Woods PGA Tour 11

. EA Sports.

Exline, R. V. (1963). Explorations in the process of person perception: visual interaction in relation to competition, sex, and need for affiliation. Journal of Personality, 31(1), 1-20.

Fleming, M. J., & Rickwood, D. J. (2001). Effects of violent versus nonviolent video games on children’s arousal, aggressive mood, and positive mood. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 1(10), 2047–2071. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2001.tb00163.x

Foster, W. K. (1984). Cooperation in the game and sport structure of children: One dimension of psychosocial development. Education, 105(2), 201–205.

Funder, D. C., & Colvin, C. R. (1988). Friends and strangers: Acquaintanceship, agreement, and the accuracy of personality judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55(1), 149-158.

Graziano, W.G., & Eisenberg, N. (1997). Agreeableness: A dimension of personality. In R.

Hogan, J. Johnson, & S. Briggs (Eds.), Handbook of Personality Psychology, (pp. 795–824). San Diego, CA: Academic

Hays, W. L. (1958). An approach to the study of trait implication and trait similarity. In R. Tagiuri & L. Petrullo (Eds.), Person Perception and Interpersonal Behavior (pp. 289-299). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Ivory, J. D., & Kalyanaraman, S. (2007). The effects of technological advancement and violent content in video games on players feelings of presence, involvement, physiological arousal, and aggression. Journal of Communication, 57(3), 532–555. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2007.00356.x

Jensen-Campbell, L.A., & Graziano, W.G. (2001). Agreeableness as a moderator of interpersonal

conflict. Journal of Personality, 69, 323–361.

Jones, K. (2001). Sport and friendship. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 35(1), 131-140.

Kaplan, S.J. (1983).The image of amusement arcades and differences in male and female video game playing. Journal of Popular Culture, 16, 93-98.

Lenhart, A., Kahne, J., Middaugh, E. Macgill, A. R., Evans, C. & Vitak, J. (2008). Teens, video games, and civics. Retrieved February 2, 2010 from Pew Internet and American Life Project: http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2008/Teens-Video-Games-and-Civics.aspx.

Microsoft (2010). HALO Reach [Video Game]. Bungie.

Saucier, G. (1994). Mini-markers: A brief version of Goldberg’s unipolar big-five markers. Journal of Personality Assessment, 63(3), 506-517.

Schneider, B. H., Woodburn, S., Toro, M. d. P. S. d., & Udvari, S. J. (2005). Cultural and gender differences in the implications of competition for early adolescent friendship. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 51(2), 163-191.

Shafer, D. M. (2012). Causes of State Hostility and Enjoyment in Player vs. Player and Player vs. Environment Video Games. Journal of Communication, 62, 719 – 737. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01654.x

Shafer, D. M., Carbonara, C. P., & Popova, L. (2011). Spatial presence and perceived reality as predictors of motion-based video game enjoyment. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 20(6), 591-619.

Sherry, J. L., Greenberg, B., Lucas, K. & Lachlan, K. (2006). Video game uses and gratifications as predictors of use and game preference. In P. Vorderer & J. Bryant (Eds.), Playing video games: Motives, responses, and consequences (pp. 213 – 224). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Simo, J., Inger, E., Kivikangas, M., & Ravaja, N. (2012). Digital games as experiment stimulus. Proceedings of DiGRA Nordic 2012 Conference: Local and Global – Games in Culture and Society. Presented at the DiGRA Nordic 2012, University of Tampere: DiGRA.

Skalski, P., & Whitbred, R. (2010). Image versus sound: A comparison of formal feature effects on presence and video game enjoyment. PsychNology Journal, 8 (1), 67 – 84. Retrieved January 15, 2011, from www.psychnology.org.

Smith, S. L. (2006). Perps, pimps, and provocative clothing: Examining negative content patterns in video games. In P. Vorderer & J. Bryant (Eds.), Playing video games: Motives, responses, and consequences (pp. 57 – 75). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Taft, R. (1966). Accuracy of empathic judgments of acquaintances and strangers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3(5), 600-604. doi: 10.1037/h0023288

Tecmo (2005). Dead or Alive 4 [Video Game]. Team Ninja.

Tesser, A. (2001). Self-Esteem. In A. Tesser & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of social psychology: Intraindividual processes (pp. 479-498). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Tesser, A. (1988). Toward a self-evaluation maintenance model of social behavior. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology Vol. 21 (pp. 181–222). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Tesser, A., Millar, M., & Moore, J. (1988). Some affective consequences of social comparison and reflection processes: The pain and pleasure of being close. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(1), 49–61. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.1.49

Vorderer, P., Bryant, J., Piper, K., & Weber, R. (2006). Playing video games as entertainment. In P. Vorderer & J. Bryant (Eds.). Playing video games: Motives, responses, and consequences (pp. 1-9). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Williams, D. (2006). A brief social history of game play. In P. Vorderer & J. Bryant (Eds.). Playing video games: Motives, responses, and consequences (pp. 197-212). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Williams, R. B., & Clippinger, C. A. (2002). Aggression, competition and computer games: computer and human opponents. Computers in Human Behavior, 18(5), 495–506. doi:10.1016/S0747-5632(02)00009-2

Wright, J. C., Huston, A. C., Vadewater, E. A., Bickham, D. S., Scantlin, R. M., Kotler, J. A., et al. (2001). American children’s use of electronic media in 1997: A national survey. Applied Developmental Psychology, 22, 31-47.