“Love me!” Examining the effect of music censorship on sexual priming and sexual cognitions

Chrysalis L. Wright, PhD

University of Central Florida

Maria Toro Arenas

University of Central Florida

Priscilla Martinez

University of Central Florida

Kathryn McMullen

University of Central Florida

Rhea Philip

University of Central Florida

The current study was a quasi-experimental design examining the relationship between exposure to sexual content in music, sexual priming, and sexual cognitions among 165 male and female emerging adult college students. Participants were randomly assigned to four experimental conditions where they viewed either music videos containing explicit sexual lyrics, censored music videos, music videos with no explicit content, or no videos. Participants then completed a measure of sexual priming and items related to their sexual cognitions. Results indicated that exposure to censored or uncensored music videos containing sexual content was associated with increased sexual priming, indicating that music censorship is ineffective. However, this was a short-term effect as sexual priming was not related to participants’ sexual cognitions. The effectiveness of music censorship and implications for reducing priming are discussed.

Keywords: censorship, priming, sexual cognitions, music

Chrysalis L. Wright, Ph.D. is the Director of the Media & Migration Lab and faculty member in the psychology department at the University of Central Florida. Her research centers around media (broadly defined) and technological influences on developmental processes and behavior. She can be reached at Chrysalis.Wright@ucf.edu.

Maria Toro Arenas recently completed her B.S. degree in psychology from the University of Central Florida. Maria was a research assistant in the Media & Migration Lab for three semesters and plans to attend graduate school for clinical psychology. She can be reached at mjta96@knights.ucf.edu.

Priscilla Martinez recently completed her B.S. degree in psychology from the University of Central Florida. Priscilla was a research assistant in the Media & Migration Lab for four semesters and plans to pursue a doctorate degree in clinical psychology. She can be reached at Pmartinez22@knights.ucf.edu.

Priscilla Martinez recently completed her B.S. degree in psychology from the University of Central Florida. Priscilla was a research assistant in the Media & Migration Lab for four semesters and plans to pursue a doctorate degree in clinical psychology. She can be reached at Pmartinez22@knights.ucf.edu.

Kathryn McMullen is a senior at the University of Central Florida majoring in psychology. Kathryn was a research assistant in the Media & Migration lab for one semester and aims to become a physician’s assistant. She can be reached at Kathryn.mcmullen@knights.ucf.edu.

Rhea Philip recently completed her B.S. degree in psychology at the University of Central Florida. Rhea was a research assistant in the Media & Migration lab for five semesters and plans to attend graduate school for school psychology. She can be reached at rheaphilip@knights.ucf.edu.

Author Note:

Chrysalis L. Wright, Department of Psychology, University of Central Florida.

The data presented, the statements made, and the views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Chrysalis L. Wright, Department of Psychology, University of Central Florida, 4000 Central Florida Blvd, Orlando, FL 32816. E-mail: Chrysalis.Wright@ucf.edu.

Introduction

Concern over explicit content in music picked up speed during the 1980’s, shortly after the launch of Music Television (MTV), Video Hits One (VH1), and gangsta rap, as well as the soaring popularity of heavy metal music (Adaso, 2016; Christe, 2003; Peake, 2017). It was during this time that the Parents’ Music Resource Center (PMRC) formed, which presumed that exposure to explicit content in music would be associated with outcomes such as unplanned pregnancies, STIs, drug use, and so on (Chastagner, 1999). However, at the time, there was little scientific evidence to support their claim. Nonetheless, due to their efforts, after Senate meetings in 1985, the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) agreed to ask its members, comprised of 85% of American record companies, to affix a warning label on music albums, termed the parental advisory label (PAL), or print the lyrics of songs on the sleeve (Chastagner, 1999).

The RIAA (2016) agrees that certain music releases contain explicit lyrics, including graphic depictions of violence, sex, and substance abuse. They also agree that this content should be identified so parents and consumers are aware of the content of their purchase. The RIAA continues to administer the PAL program and updates the program as advances in technology change how consumers listen to music. The RIAA also recommends that artists create edited versions of songs that originally contain explicit content.

Additionally, the Federal Communications Commission regulates interstate and international communications by radio, television, wire, satellite, and cable in the United States (Federal Communications Commission [FCC], 2016) under the guise of protecting children from potentially harmful programming (Conrad, 2010; FCC, 2016). However, some have proposed that there is a lack of concrete evidence that exposure to such content could harm children (Rivera-Sanchez, 1995). Furthermore, the United States Congress has specified that indecent and profane material can only be broadcast during times of day when it is less likely that children would be in the audience, specifically between 6:00 a.m. and 10:00 p.m. Those who violate these regulations can be stringently fined, imprisoned, or both (Conrad, 2010; Rivera-Sanchez, 1995). The FCC may also revoke the license of a radio station, withhold or place conditions on the renewal of a broadcast license, or issue a warning for the broadcast of obscene or indecent content (Conrad, 2010).

Many in the recording industry have participated in self-censorship to avoid penalties of the FCC. The recording industry may play radio edits of songs or bleep out words and material that could be considered obscene or indecent (Conrad, 2010; Kelly, Goldman, Briggs, & Chambers, 2009). The intent of this self-censorship appears to be to prohibit awareness of explicit material. However, it is unclear if censorship is effective in this regard.

Exposure to Explicit Content in Music

While the PMRC did not base their assumption regarding the potential negative impact of explicit music content on consumers on scientific evidence (Chastagner, 1999), a plethora of research has been conducted since the 1980’s, with most research showing that there is a relationship. This line of research has mostly focused on substance use (Lim, Hellard, Hocking, 2008; Lim, Hellard, Hocking, & Spelman, 2010; Mulder et al., 2009; 2010; Wright & DeKemper, 2015), violence (Anderson, Carnagey, & Eubanks, 2003; Coyne & Padilla-Walker, 2015; Fischer & Greitemeyer, 2006; Mast & McAndrew, 2011; Pieschl & Fegers, 2016), and sexual attitudes or activity (Arnett, 1991; Aubrey, Hopper, & Mbure, 2011; Burgess & Burpo, 2012; Coyne & Padilla Walker, 2015; Johnson-Baker, Markhan, Baumler, Swain, & Emery, 2015; Kaestle, Halpern, & Brown, 2007; Martino et al., 2006; Peterson & Pfost, 1989; Peterson, Wingood, DiClemente, Harrington, & Davies, 2007; Primack, Douglas, Fine, & Dalton, 2009; Wingood et al., 2003; Wright, 2014; Wright & Qureshi, 2015; Wright & Rubin, 2017; Zhang, Miller, & Harrison, 2008). While most research has reported a relationship between music content and these outcomes, a few studies have reported a minimal effect or no effect (Ferguson, Nielsen, & Markey, 2016; Sprankle, End, & Bretz, 2012).

Since it is not probable to include all three main outcomes in this study, the current study focused on sexual attitudes. Renard and Byers (1999) first introduced the theoretical framework regarding sexual cognitions. This term was used to summarize a range of thoughts, fantasies, and images related to sexual activity, one’s own sexual behaviors, as well as implications associated with those behaviors. Sexual cognitions can be either negative or positive based on the level of acceptance and pleasure associated with the cognition (Renard & Byers, 1999). More recent research has associated positive sexual cognitions with intimate themes and negative sexual cognitions with themes of dominance for men and submission for women (Moyano & Sierra, 2014). Practicing safer sex, perceived peer norms related to sexual activity, and the idea of positive or negative outcomes related to sexual practices are all examples of what Renard and Byers (1999) called sexual cognitions (Ward, Epstein, Caruthers, & Merriwether, 2011).

Sexual references in music and other forms of media may influence the sexual qualities that are desired for both men and women (Carpentier, 2014). In fact, numerous studies have found a relationship between viewing music videos or exposure to sexual content in music and holding negative sexual cognitions (Hansen & Hansen, 1988; Kalof, 1999; Kistler & Lee, 2009; Strouse, Buerkel-Rothfuss, & Long, 1995; Ward, 2002; Ward, Handbrough, & Walker, 2005; Ward et al., 2011; Wright & Rubin, 2017; Zhang et al., 2008).

Furthermore, the majority of research in this area explains the relationship between exposure to music content and various outcomes based on priming (Anderson et al., 2003; Aubrey et al., 2011; Carpentier, 2014; Carpentier, Knobloch-Westerwick, & Blumhoff, 2007; Fischer & Greitemeyer, 2006; Timmerman et al., 2008). Priming generally involves a form of stimulation (in this study, music content) of people’s mental representations of events or situations (in this study, sex), occurring outside of mental awareness, that then influences attitudes or actions (Eitam & Higgins, 2010; Higgins & Eitam, 2014; Loersch & Payne, 2011; 2014). Some research has indicated that if people are aware of the primed influence on their attitudes or actions, the priming effect dissolves (Higgins, 1996; Loersch & Payne, 2014). Other research has indicated that the priming effect is generally one that is short-term (e.g., seconds) rather than long-term (e.g., minutes, days, etc.) (Wentura & Rothermund, 2014).

Music Censorship Effectiveness

If the goal of music censorship is to prohibit cognizance of explicit material, then one must assume that music containing censored content would not prime consumers in the same manner as unedited explicit content. However, research examining the effectiveness of music censorship is rather sparse. Research that has been conducted in this area suggests that censorship is ineffective in that listeners can generate some of the censored words on their own using the context of the song as a guide (i.e., generation effect) (Gabriel et al. 2016; Kelly et al., 2009) even though consumers have reported that they feel less influenced by music content when exposed to censored music (McLeod et al., 1997). Other research has found no difference in participants’ sexual attitudes after exposure to censored and uncensored sexually explicit music (Sprankle & End, 2009). Additionally, using the PAL and/or censoring music content may increase attractiveness to age-inappropriate media for young consumers (Jockel, Blake, & Schlutz, 2013). Censoring music content may even project ideas of inappropriateness onto censored songs or artists (North & Hargreaves, 2005) and may promote negative views on specific music genres (e.g., rap music) (Schneider, 2011). Even with a lack of research backing, music censorship has much support among the general public and policymakers (Lynxwiler & Gay, 2000).

Current Study

The current study was a quasi-experimental design that examined music censorship on the priming of participants and their reported sexual cognitions. This study focused on sexual content in music and sexual priming. Participants were randomly assigned to four experimental conditions containing male and female participants aged 18-25 and were shown a series of music videos containing explicit sexual lyrical content, the same music videos with censored sexual lyrical content, popular music videos with no sexually explicit content, or no music videos. Participants then completed a timed word completion task to determine the level of sexual priming as well as a series of questions related to their sexual cognitions. This study had two hypotheses. Note that we also examined the possible influence of participant gender, race, ethnicity, and social class on these hypothesized relationships.

H1: There would be no difference in sexual priming among participants based on the experimental condition.

H2: Those who were more sexually primed would hold more negative sexual cognitions than those who were not sexually primed.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Participants included a total of 165 male and female emerging adult (aged 18-25 years) college students from a large southeastern public research university who were recruited through their undergraduate psychology courses and received class credit for participation. Participants included 78 females (47.3%) and 87 males (52.7%). Participants identified themselves as white, non-Hispanic (n = 74, 44.8%), Hispanic (n = 39, 23.6%), African American (n = 27, 16.4%), Asian (n = 15, 9.1%), and other (n = 7, 4.2%).

Participants were randomly assigned to four experimental conditions. Participants in condition one (n = 43; 21 males and 22 females) were exposed to two consecutive music videos of popular songs that contained uncensored explicit sexual content. The first song was “Love Me” by Lil’ Wayne (04:25 minutes) and the second song was “High School” by Nicki Minaj (04:07 minutes). Participants in condition two (n = 48; 26 males; 22 females) were exposed to the same music videos as those in condition one. However, the versions they were exposed to contained censored sexually explicit lyrics. The visual content in the music videos was identical. Participants in condition three (n = 26; 13 males and 13 females) were exposed to two consecutive music videos of popular songs that did not contain explicit lyrics. The first song was “Rise” by Katy Perry (03:17 minutes) and the second song was “Sucker for Pain” by Lil Wayne, Wiz Khalifa, Imagine Dragons with Logic, Ty Dolla $ign, and X Ambassadors (04:58 minutes). Participants in condition four (n = 48; 27 males and 21 females) were not exposed to any music videos.

Upon arrival to the study, participants were first provided an informed consent form. After agreeing to participate, researchers welcomed participants to the study and informed them of the intent of the study and procedures. Questionnaires were then handed to participants face down. Participants were asked not to begin the questionnaire until told to do so. Participants were then exposed to the music videos in their condition, with the exception of condition four which did not view any music videos. Once the videos were finished, participants were asked to turn over their questionnaire and complete the timed word-completion task. Participants had a total of 30-seconds to complete a list of 20 words. Participants then completed the remaining sections of the questionnaire, which included questions related to sexual cognitions as well as general demographic questions. It took participants approximately 30-minutes to complete the study.

Measures

Sexual priming. To assess sexual priming, participants completed a 30-second timed work-completion task, developed for the purposes of this study, immediately after viewing the music videos in their condition. Condition four, however, viewed no music videos and completed the word-completion task as soon as the study began. The word-completion task included a total of 20 words that were missing one letter. Each word could have been completed as either a sexual reference or a non-sexual reference. Examples include “_orn,” which could have been completed as corn, horn, torn, or worn as non-sexual references and porn as a sexual reference and “d_ck,” which could have been completed as duck, dock, or deck as non-sexual references and dick as a sexual reference. The total number of words completed in a sexual reference was used to indicate the level of sexual priming among participants in all four conditions.

Sexual cognitions. Participants answered a total of 79 questions to assess their sexual cognitions, which examined views related to both positive and negative sexual cognitions. These questions were used to assess nine themes of sexual cognitions found in previous research (i.e., dating is a game, men are sex driven, women are sex objects, men are tough, feminine and masculine ideals, sexual stereotypes, adversarial sexual beliefs, sexual conservatism) (Burt, 1980; ter Bogt, Engles, Bogers, & Kloosterman, 2010; Ward 2002; Ward et al., 2005; 2011). Alpha reliabilities ranged from .64 to .82. Participants responded using a 6-point Likert type scale with 1 (strongly disagree) and 6 (strongly agree). Items for each sexual cognition were summed to derive at a total score.

As with previous research (Wright & Rubin, 2017), all sexual cognitions (i.e., dating is a game, men are sex driven, women are sex objects, men are tough, feminine and masculine ideals, sexual stereotypes, adversarial sexual beliefs, sexual conservatism) were correlated. Consequently, following previous research in this area (Wright & Rubin, 2017), the factor structure of the nine sexual cognition themes was examined. Examination of scree plots indicated that a single factor was evident in that all of the sexual cognitions loaded at > .50 on this factor (see Costello & Osborne, 2005). Considering that the sexual cognitions can be classified as negative, based on Renaud and Byers (1999), a negative sexual cognition aggregate measure was developed and used in analyses (Chronbach alpha = .86). On the aggregate measure, the minimum score was 144 and the maximum score was 419.

Demographic questionnaire. Participants answered three questions to assess participants age, race, ethnicity, and gender.

Social class. Social class was assessed using measures of parental education, income and occupation as well as measures of self-identified social class identity (Rubin, 2012; Rubin & Wright, 2015; Rubin et al., 2014). Items were transformed to z scores and averaged to derive at a total social class measure that was used in analyses. Alpha reliability in the current study was .72. Final scores ranged from 2.56 to 6.67, with higher scores indicating a higher social class.

Results

Preliminary analyses were conducted to assess the reliability, distributional characteristics, and intercorrelations of measures and the extent of missing data. Missing data were minimal for most variables (< 2%) and were found to be missing completely at random (MCAR). Therefore, a simple mean substitution imputation method was used (Kline, 2005). Analyses for each hypothesis were as follows: (1) an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was conducted to determine the difference in sexual priming among the four different experimental conditions, while controlling for participants’ gender, race, ethnicity, and reported social class (H1) and (2) a regression analysis was conducted to determine if the level of sexual priming was related to participants’ sexual cognitions (H2).

Intercorrelation of Study Variables

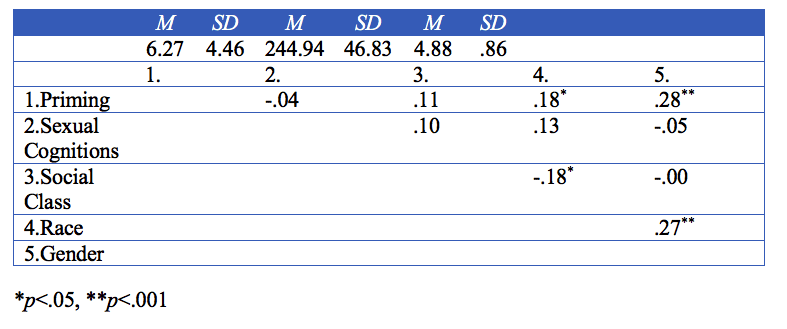

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations of study variables can be found in Table 1. On average, participants responded to 6.27 out of 20 items (31.35%) on the timed word-completion task as a sexual reference, indicating sexual priming. Additionally, participants average sexual cognition score was almost the median of the range of scores (144 – 419). In terms of social class, the average for the current study appears to be middle class.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Intercorrelations of Variables

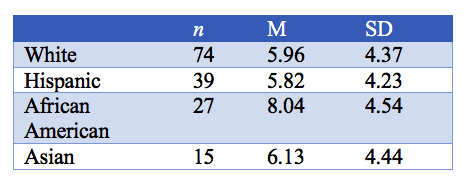

There were also positive correlations among participant race and ethnicity (coded as 1 = white and 0 = non-white for statistical purposes) and participant gender and the level of sexual priming. An analysis of variance (ANOVA), however, did not find any significant differences in level of sexual priming based on participant race, F (5, 156) = 1.91, p = .09 (see Table 2). This may have been due to limitations in sample size among some of the race and ethnicity variables. Results of an ANOVA, however, indicated a significant difference in the level of sexual priming based on participant gender, F (1, 162) = 13.68, p = .00, with female participants having higher levels of sexual priming (M = 7.57, SD = 4.60) than male participants (M = 5.08, SD = 4.02). Results of intercorrelations also indicated a negative relationship between participant race and ethnicity and social class as well as participant race and ethnicity and gender.

Table 2. Sexual Priming and Participant Race

Sexual Priming

An ANCOVA was conducted to test the hypotheses that: (1) there would be no difference in sexual priming among those exposed to music videos containing sexually explicit lyrical content and those viewing the same music videos with censored explicit lyrical content and (2) there would be a difference in sexual priming among participants who viewed no videos or those who viewed popular music videos containing no sexually explicit lyrics with those who viewed music videos containing sexually explicit lyrical content, whether censored or uncensored.

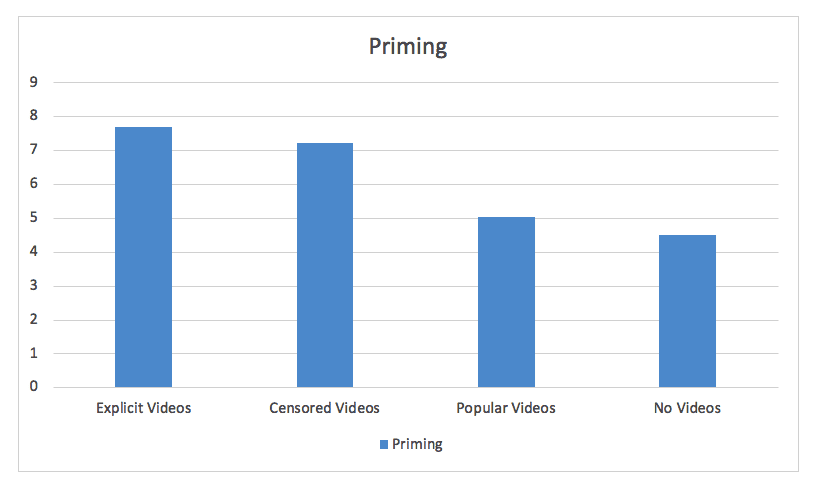

Results indicated significant differences in the level of sexual priming participants experienced based on experimental condition, after controlling for participant gender, race, ethnicity, and social class, F (3, 165) = 5.77, p = .001, η2 = .10. Participants who were exposed to the music videos containing uncensored explicit sexual lyrical content had the highest level of sexual priming (M = 7.70, SD = .63) followed by those who were exposed to the music videos containing censored explicit sexual lyrical content (M = 7.23, SD = .59). Participants who viewed popular music videos not containing explicit lyrical content had the third level of sexual priming (M = 5.05, SD = .81) and those who viewed no music videos had the lowest level of sexual priming (M = 4.68, SD = .59) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Sexual Priming and Experimental Condition

Significant differences in the level of sexual priming were also found based on participant gender, F (1, 165) = 13.68, p = .00, η2 = .08. Significant differences were not found for participant race and ethnicity, F (1, 165) = 1.34, p = .25, η2 = .01, nor social class, F (1, 165) = .07, p = .07, η2 = .02.

A follow up ANOVA was conducted with experimental condition and participant gender as the predictor variables and level of sexual priming as the dependent variable in order to test if an interaction effect existed. Results found significant main effects for both experimental condition, F (3, 156) = 5.82, p = .001, η2 = .10, and participant gender, F (1, 156) = 12.64, p = .00, η2 = .08. However, no significant interaction effect was found, F (3, 156) = .88, p = .45.

Sexual Cognitions

A regression analysis was conducted to test the hypothesis that those who were more sexually primed would hold more negative sexual cognitions than those who were not sexually primed. Using the aggregate measure of negative sexual cognitions, priming was not found to be a significant influence, F (1, 164) = .24, p = .63. Follow up regression analyses using each of the nine sexual cognition themes (i.e., dating is a game, men are sex driven, women are sex objects, men are tough, feminine and masculine ideals, sexual stereotypes, adversarial sexual beliefs, sexual conservatism) were then conducted. For each analysis, the level of sexual priming was not found to influence participants’ sexual cognitions. As an additional follow-up analysis, an ANOVA was conducted to determine if there were differences in participants’ negative sexual cognitions based on experimental condition. Results were also not significant, F (3, 161) = 1.99, p = .12.

Discussion

The current study examined music censorship on the sexual priming of participants and their subsequent reported sexual cognitions using a quasi-experimental design. Participants included male and female emerging adult college students who were randomly assigned to four experimental conditions: (1) viewed music videos containing sexually explicit lyrics, (2) viewed music videos containing censored sexually explicit lyrics, (3) viewed popular music videos containing no explicit lyrics, and (4) viewed no music videos. Participants in each condition completed a timed word-completion task to assess sexual priming and completed a series of questions related to their sexual cognitions.

Results of the study partially supported our initial hypotheses. Our first hypothesis was supported by the current findings: there would be no difference in sexual priming among participants based on the experimental condition. Our second hypothesis, that those who were more sexually primed would hold more negative sexual cognitions than those who were not sexually primed, was not supported by the findings of the current study.

Music Censorship, Priming Effects, and Sexual Cognitions

In general, there is much support among the general population (Lynxwiler & Gay, 2000), policymakers (Conrad, 2010; FCC, 2016), and the recording industry (RIAA, 2016) for the censorship of explicit content in music. However, there has been doubt that this support is supported by scientific findings (Rivera-Sanchez, 1995). Findings of the current study indicate that this support may be unfounded.

The current study focused on negative sexual cognitions and aimed to determine if exposure to explicit sexual content in music would sexually prime participants, which would then influence their sexual cognitions. In terms of sexual priming, the current study found a significant difference in those who viewed either popular music videos containing no sexually explicit lyrics or no music videos and those who viewed music videos containing sexually explicit lyrics, whether censored or uncensored. However, there was no significant difference in the level of sexual priming among those who viewed censored or uncensored music videos containing sexually explicit lyrics. Additionally, it should be noted that there was a medium-sized effect for exposure to sexual content in music and sexual priming among participants (Field, 2009).

These results indicate that generally, music censorship is ineffective. While the goal of censorship is to proscribe awareness of explicit content, leading to a reduction in negative consequences related to exposure to such content, if those exposed to both censored and uncensored music have similar levels of priming, the censorship is not effective in this regard. While research in this area is rather limited, the ineffectiveness of music censorship may be related to the generation effect (Gabriel et al., 2016; Kelly et al., 2009). Additional research is needed to determine why music censorship does not reduce or eliminate sexual priming. Furthermore, considering that censorship does not reduce the priming effect, it may be more effective to educate consumers on the nature of the content and possible consequences of exposure. Some studies have found that if people are aware of the priming effect on attitudes or actions, the priming effect disappears (Higgins, 1996; Loersch & Payne, 2014).

Furthermore, while the level of sexual priming was similar for those exposed to censored and uncensored sexual lyrical content in music videos, priming did not have an effect on participants reported sexual cognitions. Additionally, results did not find a significant relationship between exposure to sexual content in music and negative sexual cognitions. This disagrees with numerous studies that have reported a relationship (Hansen & Hansen, 1988; Kalof, 1999; Kistler & Lee, 2009; Strouse et al., 1995; Ward, 2002; Ward et al., 2005; 2011; Wright & Brandt, 2015; Wright & Rubin, 2017; Zhang et al., 2008), often explaining their results based on a priming effect (Anderson et al., 2003; Aubrey et al., 2011; Carpentier, 2014; Carpentier et al., 2007; Fischer & Greitemeyer, 2006; Timmerman et al., 2008).

In the current study, it appears as though exposure to sexual content in music (censored or uncensored) was associated with a short-term priming effect in that participants completed the timed word-completion task within seconds of viewing the music videos. However, it does not appear that priming resulted in a long-term effect in that participants answered a series of questions related to their sexual cognitions several minutes after being exposed to sexual content in music (censored or uncensored) (Wentura & Rothermund, 2014). Further research is needed to determine if priming can best explain the relationship between sexual content in music and the permissive sexual attitudes and stereotypical sex roles often found in research (Hansen & Hansen, 1998; Kalof, 1999; Kistler & Lee, 2009; Strouse et al., 1995; Ward, 2002; Ward et al., 2005; 2011; Wright & Brandt, 2015; Wright & Rubin, 2017; Zhang et al., 2008).

Limitations

There are some limitations of the current study that merit discussion, including the sample used, length of exposure to sexual content in music videos, and possible social desirable answers to items related to sexual cognitions. While policymakers claim that their intent in censorship is to reduce possible harm to children (Conrad, 2010; FCC, 2016), the sample utilized in the current study consisted solely of emerging adult (aged 18-25) college students. However, numerous previous studies examining the impact of sexual content in music on participant’s sexual attitudes and stereotypical sex roles have been conducted with a college student sample, with many finding a relationship between the two (Hansen & Hansen, 1998; Kalof, 1999; Kistler & Lee, 2009; Strouse et al., 1995; Ward, 2002; Ward et al., 2005; 2011; Wright & Brandt, 2015; Wright & Rubin, 2017; Zhang et al., 2008). An additional limitation related to the sample used is in regard to sample size. The current study included a total of 165 male and female participants, which may have resulted in reduced power. Generally, 180 participants are desired with a minimum of 45 participants in each experimental condition, which was not met for two of our experimental conditions. However, Keppel (1991) states that there is not a specified rule regarding unequal sample sizes and heterogeneity of variance when conducting one-way ANOVAs, which were conducted in this study.

Additionally, exposing participants to an average of 8 minutes and 13 seconds of music videos is probably not representative of the frequency that they are exposed to music videos in their daily life. The RIAA (2016) has reported that Americans listen to music an average of four hours each day. Repetitive exposure to content in music may be associated with increased views of what is portrayed in media is normal behavior, based on the cultivation theory (Cohen & Weimann, 2000; Gerber, Gross, Morgan, & Signorielli, 1994). This may partially explain why brief exposure to sexual content in music did not influence participants reported sexual cognitions.

Furthermore, participants may have responded in a socially desirable manner when answering items related to their sexual cognitions due to the sensitive nature of some of the items. However, the items used in the current study to assess negative sexual cognitions have been used in several previous studies that did find a significant relationship between exposure to sexual content in music and negative sexual cognitions (Burt, 1980; ter Bogt et al., 2010; Ward, 2002; Ward et al., 2005; 2011; Wright & Rubin, 2017).

References

Adaso, H. (2016). Gangsta rap. ThoughtCo. Retrieved from https://www.thoughtco.com/what-is-gangsta-rap-2857307

Anderson, C. A., Carnagey, N. L., & Eubanks, J. (2003). Exposure to violent media: The effects of songs with violent lyrics on aggressive thoughts and feelings. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(5), 960-971. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.960

Arnett, J. (1991). Heavy metal music and reckless behavior among adolescents. Journal of youth and adolescence, 20(6), 573-592. doi: 10.1007/BF01537363

Aubrey, J. S., Hopper, K. M., & Mbure, W. G. (2011). Check that body! The effects of sexually objectifying music videos on college men’s sexual beliefs. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 55, 360-379. doi: 10.1080/08838151.2011.597469

Burgess, M. C. R., & Burpo, S. (2012). The effect of music videos on college student’s perceptions of rape. College Student Journal, 46, 748-763.

Burt, M. R. (1980). Cultural myths and support for rape. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38, 217-230.

Carpentier, F. R. D. (2014). When sex is on the air: Impression formation after exposure to sexual music. Sexuality & Culture, 18, 818-832. doi:10.1007/s12119-014-9223-8

Carpentier, F. R. D., Knobloch-Westerwick, S., & Blumhoff, A. (2007). Naughty versus nice: Suggestive pop music influences on perceptions of potential romantic partners. Media Psychology, 9, 1-17. doi:10.1080/15213260709336800

Chastagner, C. (1999). The parent’s music resource center: From information to censorship. Popular Music, 18 (2), 179-192.

Christe, I. (2003). Sound of the Beast: The Complete Headbanging History of Heavy Metal. HarperCollins.

Cohen, J. & Weimann, G. (2000). Cultivation revisited: Some genres have some effects on some viewers. Communication Reports, 13, 99.

Conrad, M. (2010). The new paradigm for American broadcasting – changing the content regulation regimen in the age of new media. International Review of Law, Computer, & Technology, 24 (3), 241-249.

Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. W. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment Research & Evaluation, 10(7).

Coyne, S. M., & Padilla-Walker, L. M. (2015). Sex, violence, & rock n’ roll: Longitudinal effects of music on aggression, sex, and prosocial behavior during adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 4196-104. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.03.002

Eitam, B., & Higgins, E. T. (2010). Motivation in mental accessibility: Relevance of a representation (ROAR) as a new framework. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4, 951-967.

Federal Communications Commission. (2016). Information retrieved form https://www.fcc.gov/media/radio/public-and-broadcasting#FCC

Ferguson, C. J., Nielsen, R. L., & Markey, P. M. (2016). Does sexy media promote teen sex? A meta-analytic and methodological review. Psychiatric Quarterly, doi:10.1007/s11126-016-9442-2+

Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS 3rd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Fischer, P., & Greitemeyer, T. (2006). Music and aggression: The impact of sexual-aggressive song lyrics on aggression-related thoughts, emotions, and behavior toward the same and the opposite sex. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32, 1165-1176. DOI: 10.1177/0146167206288670

Gabriel, D., Wong, T. C., Nicolier, M., Giustiniani, J., Mignot, C., Noiret, N., & … Vandel, P. (2016). Don’t forget the lyrics! Spatiotemporal dynamics of neural mechanisms spontaneously evoked by gaps of silence in familiar and newly learned songs. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 132, 18-28. doi:10.1016/j.nlm.2016.04.011

Gerbner, G. Gross, L., Morgan, M., & Signorielli, N. (1994). Growing up with television: The cultivation perspective. In J. Bryand & D. Zillman (Eds.) Media effects: Advances in theory and research (pp.17-41). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Hansen, C. H., & Hansen, R. D. (1988). How rock music videos can change what is seen when boy meets girl: Priming stereotypic appraisal of social interactions. Sex Roles, 19(5-6), 287-316. doi:10.1007/BF00289839

Higgins, E. T. (1996). Knowledge activation: Accessibility, applicability, and salience. In E. T. Higgins and A. W. Kruglanski (Eds.), Social Psychology: Handbook of basic principles (pp. 133-168). New York: Guilford.

Higgins, E. T., & Eitam, B. (2014). Priming…Shmiming: It’s about knowing when and why stimulated memory representations become active. Social Cognition, 32, 225- 242.

Jöckel, S., Blake, C., & Schlütz, D. (2013). Influence of age-rating label salience on perception and evaluation of media: An eye-tracking study. Journal of Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, And Applications, 25(2), 83-94. doi:10.1027/1864-1105/a000086

Johnson-Baker, K. A., Markhan, C., Baumler, E., Swain, H., & Emery, S. (2015). Rap music use, perceived peer behavior, and sexual initiation among ethnic minority youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58, 317-322.

Kalof, L. (1999). The effects of gender and music video imagery on sexual attitudes. The Journal of Social Psychology, 139(3), 378-385. doi: 10.1080/00224549909598393

Kaestle, C. E., Halpern, C. T., & Brown, J. D. (2007). Music videos, pro wrestling, and acceptance of date rape among middle school males and females: An exploratory analysis. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40, 185–187.

Kelly, M. R., Goldman, B. A., Briggs, J. E., & Chambers, J. W. (2009). Ironic effects of censorship: Generating censored lyrics enhances memory. In M. R. Kelley, M. R. Kelley (Eds.), Applied memory (pp. 1-19). Hauppauge, NY, US: Nova Science Publishers.

Keppel, G. (1991). Design and analysis: A researcher’s handbook. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall.

Kistler, M. E., & Lee, M. J. (2009). Does exposure to sexual hip-hop music videos influence the sexual attitudes of college students? Mass Communication and Society, 13, 67–86.

Kline, R. B. 2005. “Principles and practice of structural equation modeling.” NY: The Guildford Press.

Lim, M. S. C., Hellard, M. E., Hocking, J. S., & Aitken, C. K. (2008). A cross-sectional survey of young people attending a music festival: Associations between drug use and musical preference. Drug and Alcohol Review, 27, 439–441. doi:10.1080/09595230802089719

Lim, M. S. C., Hellard, M. E., Hocking, J. S., Spelman, T. D., & Aitken, C. K. (2010). Surveillance of drug use among young people attending a music festival in Australia, 2005–2008. Drug and Alcohol Review, 29, 150–156. doi:10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00090.x

Loersch, C., & Payne, B. K. (2011). The situated inference model an integrative account of the effects of primes on perception, behavior, and motivation. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(3), 234-252.

Loersch, C., & Payne, B. K. (2014). Situated inference and the what, who, and where of priming. Social Cognition, 32, 137-151.

Lynxwiler, J., & Gay, D. (2000). Moral boundaries and deviant music: public attitudes toward heavy metal and rap. Deviant Behavior, 21, 63-85. doi: 10.1080/016396200266388

Martino, S. C., Collins, R. L., Elliott, M. N., Strachman, A., Kanouse, D. E., & Berry, S. H. (2006). Exposure to degrading versus nondegrading music lyrics and sexual behavior among youth. Pediatrics, 118, e430–e441. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-0131

Mast, J. F., & McAndrew, F. T. (2011). Violent lyrics in heavy metal music can increase aggression in males. North American Journal of Psychology, 13, 63.

Moyano, N., & Sierra, J. C. (2014). Positive and negative sexual cognitions: Similarities and differences between men and women from southern Spain. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 29, 454–466.

McLeod, D. M., Eveland, W. P., & Nathanson, A. I. (1997). Support for censorship of violent and misogynic rap lyrics: An analysis of the third-person effect. Communication Research, 24, 153-174. doi: 10.1177/009365097024002003

Mulder, J., Ter Bogt, T. F. M., Raaijmakers, Q. A. W., Gabhaim, S. N., Monshouwer, K., & Vollebergh, W. A. M. (2009). The soundtrack of substance use: Music preference and 10826080802347537

Mulder, J., Ter Bogt, T. F. M., Raaijmakers, Q. A. W., Gabhaim, S. N., Monshouwer, K., & Vollebergh, W. A. M. (2010). Is it the music? Peer substance use as a mediator of the link between music preferences and adolescent substance use. Journal of Adolescence, 33, 387–394. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.09.001

North, A. C., & Hargreaves, D. J. (2005). Brief report: Labelling effects on the perceived deleterious consequences of pop music listening. Journal of Adolescence, 28(3), 433-440. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.09.003

Peake, S. (2017). Profile and history of ‘80s cable network and music tastemaker MTV. ToughtCo. Retrieved from https://www.thoughtco.com/history-80s-cable-network-mtv-9994

Peterson, D. L., & Pfost, K. S. (1989). Influence of rock videos on attitudes of violence against women. Psychological Reports, 64, 319–322.

Peterson, S. H., Wingood, G. M., DiClemente, R., Harrington, K., & Davies, S. (2007). Images of sexual stereotypes in rap videos and the health of African American female adolescents. Journal of Women’s Health, 16, 1157-1164. DOI: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0429

Pieschl, S., & Fegers, S. (2016). Violent lyrics = Aggressive listeners” Effects of song lyrics and tempo on cognition, affect, and self-reported arousal. Journal of Media Psychology, 28, 32-41. DOI: 10.1027/1864-1105/a000144

Primack, B. A., Douglas, E. L., Fine, M. J., & Dalton, M. A. (2009). Exposure to sexual lyrics and sexual experience among urban adolescents. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 36, 317- 323. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2008.11.011

Recording Industry Association of America (2016). Information obtained from www.riaa.com

Renaud, C., & Byers, S. (1999). Exploring the Frequency, diversity, and content of University students’ positive and negative sexual cognitions. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 8, 17–30.

Rivera-Sanchez, M. (1995). The origins of the ban on ‘obscene, indecent, or profane’ language of the Radio Act of 1927. Journalism & Mass Communication Monographs, (149), 1.

Rubin, M. (2012). Social class differences in social integration among students in higher education: A meta-analysis and recommendations for future research. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 5, 22–38. doi:10.1037/a0026162.

Rubin, M. N., S. Denson, K. E. Kilpatrick, T. Matthews, D. Stehlik, and Zyngier. (2014). ’I am working-class’: Subjective self-definition as a missing measure of social class and socioeconomic status in higher education research. Educational Researcher, 43, 196–200. doi:10.3102/0013189X14528373.

Schneider, C. J., (2011). Culture, rap music, “bitch,” and the development of the censorship frame. American Behavioral Scientist, 55, 36–56. doi: 10.1177/0002764210381728

Sprankle, E. L., & End, C. M. (2009). The effects of censored and uncensored sexually explicit music on sexual attitudes and perceptions of sexual activity. Journal of Media Psychology, 21(2), 60-68. doi:10.1027/1864-1105.21.2.60

Sprankle, E., End, C., & Bretz, M. (2012). Sexually degrading music videos and lyrics: Their effects on males’ aggression and endorsement of rape myths and sexual stereotypes. Journal of Media Psychology, 24, 31-39. DOI: 10.1027/1864-1105/a000060

Strouse, J. S., Buerkel-Rothfuss, N., & Long, E. C. (1995). Gender and family as moderators of the relationship between music video exposure and adolescent sexual permissiveness. Adolescence, 30(119), 505.

Ter Bogt, T. M., Engels, R. E., Bogers, S., & Kloosterman, M. (2010). “Shake it baby, shake it”: Media preferences, sexual attitudes and gender stereotypes among adolescents. Sex Roles, 63, 844-859. doi: 10.1007/s11199-010-9815-1

Timmerman, L. M., Allen, M., Jorgensen, J., Herrett-Skjellum, J., Kramer, M. R., & Ryan, D. J. (2008). A review and meta-analysis examining the relationship of music content with sex, race, priming, and attitudes. Communication Quarterly, 56, 303-324. doi: 10.1080/01463370802240932

Ward, L. M. (2002). Does television exposure affect emerging adults’ attitudes and assumptions about sexual relationships? Correlational and experimental confirmation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 31, 1-15.

Ward, L., Epstein, M., Caruthers, A., & Merriwether, A. (2011). Men’s media use, sexual cognitions, and sexual risk behavior: Testing a mediational model. Developmental Psychology, 47, 592-602. doi:10.1037/a0022669

Ward, M. L., Handbrough, E., & Walker, E. (2005). Contributons of music video exposure to black adolescents’ gender and sexual schemas. Journal of Adolescent Research, 20, 143-166.

Wentura, D., & Rothermund, K. (2014). Priming is not priming is not priming. Social Cognition, 32, 47-67.

Wingood, G. M., DiClemente, R. J., Bernhardt, J. M., Harrington, K., Davies, S. L., Robillard, A., & Hook, E. (2003). A prospective study of exposure to rap music videos and African American female adolescents’ health. American Journal of Public Health, 93, 437-439.

Wright, C. L., & Brandt, J. (2015). Music’s dual influences on dyadic behaviors. Marriage & Family Review, 51, 544-563. DOI: 10.1080/01494929.2015.1060285

Wright, C. L., & DeKemper, D. (2015). Music as a mediator between ethnicity and substance use among college students, Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 15, 189-209. DOI: 10.1080/15332640.2015.1022627

Wright, C. L., & Rubin, M. (2017). “Get lucky!” Sexual content in music lyrics, videos and social media and sexual cognitions and risk among emerging adults in the USA and Australia. Sex Education, 17, 41-56. DOI: 10.1080/14681811.2016.1242402

Zhang, Y., Miller, L. E., & Harrison, K. (2008). The relationship between exposure to sexual music videos and young adults’ sexual attitudes. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 52, 368–386. doi:10.1080/08838150802205462