Cyber-kindness: Spreading kindness in cyberspace

Lee Rowland

University of Oxford and kindness.org

Dana Klisanin, Ph.D.

Evolutionary Guidance Media R&D, Inc.

Abstract:

Abstract:

In contrast to the widely reported negative aspects of human behavior online, a growing body of research is exploring the use of the Internet for spreading and facilitating prosocial behavior. Here we report on a survey (n=1013) that investigated the prevalence of altruistic and kindness-based online behavior, termed cyber-kindness. Motivations for cyber-kindness and the relationship between online and offline kind behavior were also explored. Results show that cyber-kindness is widespread within this sample, and is predominantly driven by other-oriented motivations as well as by a transpersonal sense of identity. Non-correlational self-report data provides evidence for a positive relationship between online and offline kindness. Limitations of the current study are discussed and we conclude that the phenomenon of cyber-kindness merits further empirical investigation.

Keywords: cyber-kindness; digital altruism; kindness; altruism; prosocial behavior

Dr. Lee Rowland is a research associate in anthropology at the University of Oxford and a research psychologist working with kindness.org, a New York-based non-profit organisation. He trained as an experimental psychologist at UCL and has worked as a consultant psychologist/social scientist for a range of organisations across the world, on projects primarily focused on behaviour change, social cohesion, and communication. Lee’s current main research interests are in prosocial behaviour, altruism, and kindness, and he recently oversaw the first meta-analysis of the beneficial effects of kindness in collaboration with Oxford’s Dr Oliver Scott-Curry. That study was published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology and they also jointly published a kindness experiment in the Journal of Social Psychology. His work in academia has also led to teaching posts at Oxford, UCL, the Open University UK, Southampton University and Bournemouth University, where he led a course on cyberpsychology. Lee’s writing has appeared in, amongst others, Philosophy Now, Spiked!, The Guardian, and The Psychologist, as well as a book chapter in the seminal Behavioural Conflict: Why understanding people and their motivations will prove decisive in future conflict.

Dr. Lee Rowland is a research associate in anthropology at the University of Oxford and a research psychologist working with kindness.org, a New York-based non-profit organisation. He trained as an experimental psychologist at UCL and has worked as a consultant psychologist/social scientist for a range of organisations across the world, on projects primarily focused on behaviour change, social cohesion, and communication. Lee’s current main research interests are in prosocial behaviour, altruism, and kindness, and he recently oversaw the first meta-analysis of the beneficial effects of kindness in collaboration with Oxford’s Dr Oliver Scott-Curry. That study was published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology and they also jointly published a kindness experiment in the Journal of Social Psychology. His work in academia has also led to teaching posts at Oxford, UCL, the Open University UK, Southampton University and Bournemouth University, where he led a course on cyberpsychology. Lee’s writing has appeared in, amongst others, Philosophy Now, Spiked!, The Guardian, and The Psychologist, as well as a book chapter in the seminal Behavioural Conflict: Why understanding people and their motivations will prove decisive in future conflict.

Dr. Dana Klisanin is an award-winning psychologist and futurist exploring the impact of media and digital technologies on the mythic and moral dimensions of humanity. Founder and CEO at Evolutionary Guidance Media R&D, Inc., Dana’s research, at the intersection of pro-social behavior and technology, has changed the way we think about altruism, heroism, and what we value. She serves on the boards of Kindness.org, World Futures Studies Federation, Lifeboat Foundation, and c3: Center for Conscious Creativity. Dana speaks Internationally and has been quoted and interviewed by radio and news outlets including, BBC, TIME, Fast Company, Psychology Today, Huffington Post, USA Today. Her published articles include theoretical investigations on the future of media, conscious media design, foresight communication, mindfulness, altruism, and heroism in the digital age. She has contributed chapters to numerous books including the seminal, Handbook of Heroism and Heroic Leadership. Her blog is Digital Altruism at Psychology Today. Dana’s interest in transformative technology led her to design Cyberhero League, an edtech gaming brand that empowers youth with the ability to use technology to tackle global challenges. Together with a growing network of “evolutionaries” and integral visionaries, she is helping to define a culture of thought that uses media as an instrument of spiritual awakening and world transformation. Dana can be reached through her website, www.danaklisanin.com or at dana@evolutionaryguidancemedia.com.

Dr. Dana Klisanin is an award-winning psychologist and futurist exploring the impact of media and digital technologies on the mythic and moral dimensions of humanity. Founder and CEO at Evolutionary Guidance Media R&D, Inc., Dana’s research, at the intersection of pro-social behavior and technology, has changed the way we think about altruism, heroism, and what we value. She serves on the boards of Kindness.org, World Futures Studies Federation, Lifeboat Foundation, and c3: Center for Conscious Creativity. Dana speaks Internationally and has been quoted and interviewed by radio and news outlets including, BBC, TIME, Fast Company, Psychology Today, Huffington Post, USA Today. Her published articles include theoretical investigations on the future of media, conscious media design, foresight communication, mindfulness, altruism, and heroism in the digital age. She has contributed chapters to numerous books including the seminal, Handbook of Heroism and Heroic Leadership. Her blog is Digital Altruism at Psychology Today. Dana’s interest in transformative technology led her to design Cyberhero League, an edtech gaming brand that empowers youth with the ability to use technology to tackle global challenges. Together with a growing network of “evolutionaries” and integral visionaries, she is helping to define a culture of thought that uses media as an instrument of spiritual awakening and world transformation. Dana can be reached through her website, www.danaklisanin.com or at dana@evolutionaryguidancemedia.com.

This work on this article was supported by kindness.org. Thanks to Melissa Burmester, Alexandria Henke, and Steve Rowland for research assistance.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Lee Rowland, School of Anthropology and Museum Ethnography, University of Oxford, 51/53 Banbury Road, Oxford, OX2 6PE.

E-mail: lee.rowland@anthro.ox.ac.uk

Background

Although it has become common to perceive the Internet in negative terms – in large part fueled by the substantial media coverage of cyber-bullying, trolling, hate speech, fake news, and cyber-crime – a small but growing body of research suggests that the Internet supports the expression of positive human behaviors, including generosity, kindness, altruism, and new forms of heroism (Cassidy, Brown, & Jackson, 2012, 2013; Fatkin, 2015; Klisanin, 2011, 2012, 2017; Sproull, Conley, & Moon, 2005, 2013). However, because the study of these cyber behaviors is nascent, the current literature is exceptionally insubstantial and our knowledge very limited.

In an effort to learn more about positive human interactions online, the present research sought to explore in more detail the propensity for and characteristics of online prosocial, altruistic and benevolent behavior, termed here cyber-kindness.

The biological and social sciences have provided an abundance of evidence showing that human nature is widely prosocial and altruistic (e.g. de Waal, 2009; Ricard, 2015; Rowland, 2018). It is curious therefore that human behavior in cyberspace is often portrayed so negatively (e.g. Kowalski, Limber, & Agatston, 2008; for overviews see Bartlett, 2014; Suler, 2015). In support of a more positive view of online human behavior, a 2011 study estimated that the number of people engaging in digital altruism or prosocial digital activism exceeded 100 million individuals (Klisanin, 2011). Although the number of Internet users has nearly doubled since that time (Internet World Stats, 2017), there continues to be remarkably little research conducted on the prosocial and altruistic potential of the Internet. Thus currently, very little is known about the what, who, and why of digital altruism and cyber-kindness.

Previous research by Klisanin (2011) into the prevalence of digital altruism explored altruism as a spectrum of activity ranging from the conservative to the creative (Gruber, 1997). Using Gruber’s spectrum approach, Klisanin (2011) found evidence of three forms of online altruism: everyday digital altruism, creative digital altruism, and co-creative digital altruism. Where everyday digital altruism referred to online acts of altruism that involve ease, limited moral engagement, and an element of conformity, creative and co-creative digital altruism involved creativity, heightened moral engagement, and varying levels of cooperation.

Klisanin’s (2011) study also identified a strong ‘other-oriented’ motivational basis for digital altruism. A follow-up study exploring the motives of individuals who engage in acts of online activism or digital altruism found that persons engaging in frequent (daily or weekly) prosocial cyber behaviors embodied a transpersonal sense of identity and were motivated to act on behalf of other people (Klisanin, 2012). Our use of the term transpersonal identity refers to experiences in which the sense of self extends beyond – or, transcends – the individual or personal to encompass wider aspects of humankind (Walsh & Vaughan, 1993). This is deemed to be important in the study of cyber-behavior as the Internet has often been characterized as a tool that can help humans transcend their base biological origins and imperfections (Suler, 2015). Individuals whose behaviors online are consistent with this psychological disposition were considered to represent the emergence of a new archetype: the Cyberhero. Recognizing and naming this archetype was considered an important means of bringing balance to a cyberspace lexicon that is largely skewed toward negativity. Klisanin’s initial study only partially described the characteristics of the cyberhero, leaving much still to discover. One purpose of the present study was to further explore this demographic who use the Internet to spread good, the activities that they engage in to do so, and what motivates their behavior. Klisanin’s study was on a small sample (n=298) and was over two-thirds U.S. respondents, and thus in the present study, we broaden and increase the sample size.

One criticism of many types of online prosocial behavior – for example, click-to-donate – has been that it amounts to ‘slacktivism’. That is, it is an easily achieved approach for people to feel like they are doing some good in the world, yet which results in very little real-world change. Although researchers at Georgetown University’s Center for Social Impact Communication and Ogilvy Public Relations Worldwide (2011) have shown that so-called ‘slacktivists’ are more likely to engage in cause-related initiatives than non-social media activists, the myth of online activism as a form of lazy activism persists. We sought to explore the relationship between cyber-kindness, the effort involved in performing it, and the propensity of individuals to also enact kindness offline. A study in the Balkans of the contiguity of online and offline prosocial behavior (Bosancianu, Powell, and Bratović, 2013) revealed that a positive relationship exists between “non-institutionalized online pro-social behavior and generalized offline pro-social behavior.” Additionally, Sproull et al. (2013) suggest a positive relationship between online and offline altruism. Despite these studies, the relationship between online and offline prosocial behavior is markedly under-researched.

In following Klisanin’s (2011) categorization of digital altruism, we here conjectured that cyber-kindness could be expressed by small, mostly effortless acts, right up to larger, more committed – and resource-heavy – acts. Our research, therefore, sought to investigate the frequency of engagement in a wide spectrum of cyber-kindness activities. To help us explore the kindness aspect of online prosocial behavior we used Canter et al.’s (2017) three-component model of kindness. This model – notably, the first of its kind – delineates three separable components of kindness: benign tolerance; empathetic responsivity; and, principled proaction, described below:

- Benign Tolerance: a live and let live, permissive humanity revealed in an everyday courteousness, acceptance and love of one’s fellow man.

- Empathetic Responsivity: is more personalized and emotional. It is reactive, a consideration of the specific feelings of other particular individuals.

- Principled Proaction: is driven more by cognition than emotion. It is about behaving honorably towards others and typically proactive rather than reactive. Much of this behavior is altruistic. (Canter et al., 2017, pp 203-4).

We reasoned that, if kindness were to be widely observed in cyber-space then it would likely take on forms consistent with the different manifestations of kindness in face-to-face situations. Canter et al.’s model has recently explored the different dimensions of kindness in real world settings, and thus by adopting this as a framework for kindness, it ensured our study explored activities consistent with the latest research in the field. Therefore, the cyber-kindness activities we identified and included were each relevant to at least one of the three components of kindness.

Based on the limited research available, the present study sought to further explore five premises of cyber-kindness:

- That respondents will engage in a variety of acts of cyber-kindness – categorized in accordance with Canter et al.’s (2017) three components of kindness

- That people will expend effort to perform cyber-kindness

- That a transpersonal sense of identity is an underlying factor in cyber-kindness

- That motivations for performing cyber-kindness will be primarily prosocial and other-oriented

- That there will be contiguity between online and offline kindness

Method

We conducted a literature search using Web of Science and PsycINFO for articles relating to digital kindness, digital activism, cyber-kindness, and online kindness. We also searched Google for articles and websites that aim to promote social good via the Internet (e.g. Freerice.com). Subsequently, we derived a list of cyber-kindness activities and categorized them. From this foundation we compiled a sixty-item questionnaire, as detailed below:

Demographics. Included were questions regarding respondents’ age, sex, country of residence, religious and political orientations, socio-economic status, whether they were members of the kindness.org community, and how often they use the Internet.

Cyber-kindness Activities. From our search, we identified, listed and categorized fourteen different types of cyber-kindness. Each of these items was relevant to one or more of Canter et al.’s (2017) kindness components, so we were investigating across the range of kind behaviors that could be performed online. Table 1 displays the items. We also included two negatively worded items: “I act online as though the needs of other people are NOT as important as my own needs” and “I add inflammatory comments to social media if I feel insulted”. Respondents answered how frequently they performed these behaviors on a 5-point scale from ‘Never’ to ‘Very Regularly’. Several items bear similarity to items in Klisanin’s earlier (2012) research, e.g. “When online I enjoy acting on behalf of people in need, regardless of their age, race, ethnicity, religion, or gender”, which were included to explore the prevalence of transpersonal identities in cyber-kindness.

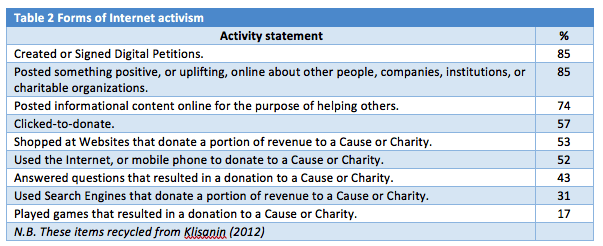

Internet Activism. Also included were the nine items pertaining to Internet Activism previously studied by Klisanin (2012), see Table 2. Although some of these partially overlap with the Cyber-kindness Activities, we included them because they ask about specific behaviors (e.g. ‘Posted informational content online for the purpose of helping others’) rather than more general kindness activities (e.g. ‘I go out of my way to do things for other people online’). Also, responses to these questions were a simple yes or no, whereas the Cyber-kindness questions asked about frequency of online behavior. We also included these questions to have contiguity with Klisanin’s earlier research into digital activism by collecting data from a broader, larger and more recent sample.

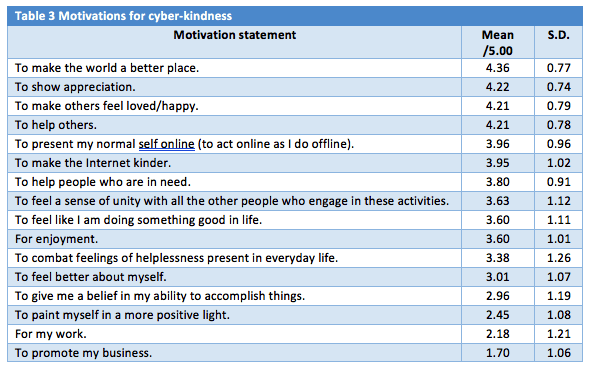

Motivations for Cyber-Kindness. Fourteen items explored the motivations for performing cyber-kindness behaviors, see Table 3. Motivational items were ‘other-oriented’, e.g. ‘To make others feel loved/happy’, and ‘self-oriented’, e.g. ‘To promote my business’. Klisanin’s (2012) previous research had supported the premise that some individuals engaging in digital activism were motivated to act on behalf of other people, animals, and the environment in the peaceful service of achieving humanity’s highest ideals and aspirations. Several items (e.g. ‘To feel a sense of unity with all the people who engage in these activities’, ‘To make the world a better place’) were included to continue exploring these ‘higher’ and ‘other-oriented’ motivations. Respondents answered whether they agreed with a statement on a 5-point Likert scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

Effort. We were interested in identifying the degree of effort people expend to perform cyber-kindness. Five items were included that attempted to probe this factor, e.g. “I actively try and spread kindness online”, “I expend a lot of effort to be kind online”. Two items were selected from Klisanin’s (2012) study: “I am being proactive when I use the Internet to support the needs of other people, animals or the environment”, and “I use the Internet to act on behalf of more than one cause or charity”. Whilst in Klisanin’s earlier study these items were employed to identify a motivation to act on behalf of humanity and a transpersonal identity, respectively, here they are included to additionally gauge the effort involved in performing cyber-kindness, with the assumption that ‘being proactive’ and acting on ‘behalf of more than one cause or charity’ requires significant prosocial effort.

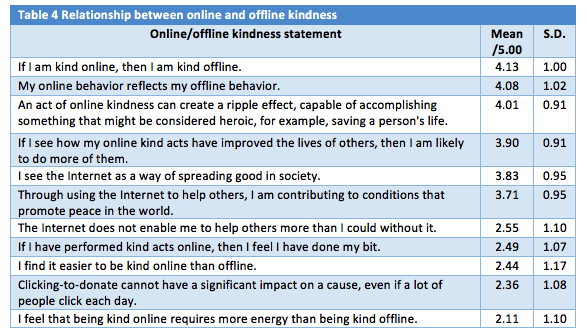

Relationship Between Online and Offline Kindness. Eleven items were included to explore the relationship between online and offline kindness, see Table 4. We also included several items previously presented in Klisanin’s (2012) research, e.g. “Clicking-to-donate cannot have a significant impact on a cause, even if a lot of people click each day” (this question is worded negatively, but is reverse coded and reported positively), as well as one item that was drawn from the digital activism literature, “An act of online kindness can create a ripple effect, capable of accomplishing something that might be considered heroic, for example, saving a person’s life”. As per our introduction, we also were interested in exploring the notion of ‘slacktivism’, so we included several relevant items, e.g. “If I have performed kind acts online, then I feel I have done my bit”, as well as a negatively worded item that is reverse coded, “I feel that being kind online requires more energy than being kind offline”.

Survey Distribution. Once the survey was created we emailed a link of the survey to several thousand kindness.org online community members who had expressed prior interest in taking part in research into kindness. Eight hundred and thirty-three completed questionnaires were obtained that way. An additional one hundred and eighty respondents were obtained using social media (kindness.org’s Facebook page) and through one author (DK) publishing an article with a link to the survey on Psychology Today. This method of obtaining respondents is subject to bias, which we discuss later on. It is, however, consistent with other work in this area to date, and extends those findings in interesting ways (Klisanin, 2011). The sample can also be regarded as a strength for the type of research undertaken here. Convenience samples or self-selecting samples can be highly informative for understanding a phenomenon, especially one largely unexplored or nascent. This is the case with cyber-kindness. Consider if we were conducting a study into cyber-bullying and wanted to get a sense of what bullying activities and tactics are common and popular, what motivates them, and whether they are consistently represented both online and offline. Studying a sample of cyber-bullies would be most informative. By studying self-selecting kindness advocates – importantly, not cyber-kindness advocates – we are able to provide some initial data into this emerging phenomenon that will serve as a useful foundation and baseline for future research.

Potential bias In order to reduce social desirability bias, all participants completed the survey anonymously online. A wide range of socially impressive activities was presented in the survey, some more status-enhancing than others – thus, if social desirability bias was prevalent, we would expect this to be reflected in the scores for the more highly impressive items. To reduce the potential for response bias regarding our rationale, we provided no information about the premises we were investigating.

Results

Demographic Data

The data are collected from 1013 respondents (14% male) who completed the questionnaire online. Respondents were from 60 countries, with 23% from the United Kingdom and a further 38% from English speaking countries (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa and USA). Respondents were from a range of political (48.7% left), religious (47% spiritual but not religious) and socio-economic (80.8% middle-income) categories. The modal age range category was 30 – 45 years (35% of sample) with respondents ranging from a 13-17 years category to a 60+ years category. 76% had previously engaged with the kindness.org community with 32% actively posting kind acts online as part of a kindness initiative. 89% reported they used the Internet every day, and 11% often.

Cyber-Kindness Activities

Respondents indicated that they performed many different types of cyber-kindness: for all the cyber-kindness questions shown in Table 1, the mean was 2.50/5.00 or greater, with “I give to others in need online, such as people needing to raise money for medical or legal assistance” being the lowest (M=2.50) and “I try to be accepting of people’s differences online, even if I disagree” being the highest (M=4.13). See Table 1 for the range of cyber-kindness activities.

Two items worded negatively were also reverse coded: “I act online as though the needs of other people are NOT as important as my own needs” (reverse coded M=2.94 SD=1.03), and “I add inflammatory comments to social media if I feel insulted” (reverse coded M=3.56 SD=0.74).

For the fourteen activities displayed in Table 1, 19.2% of the sample responded that they perform all fourteen activities, with scores of 3, 4, or 5 (very regularly). For half of the activities or more, 92.7% of the sample responded 3, 4, or 5. No respondents scored 1 (never) to all fourteen activities. These results show that cyber-kindness is widespread across our sample, with 939 individuals performing at least seven cyber-kindness activities at least occasionally.

Whilst there were sex differences in the frequency with which respondents carried out the activities in Table 1, they were typically very small. Females consistently scored slightly higher than males on mean frequencies of activities (except for the two reverse coded items mentioned above, where the males scored slightly higher). The items with the largest sex difference on means scores were: “When others express sadness online I try and comfort them” (male score – female score difference = -0.41), and, “I like to compliment others online” (male score difference – female score difference = -0.43). Both differences were statistically significant, t(142) = 1.93, p<.05, and t(142) = 2.41, p<.01, respectively.

The cyber-kindness activities in Table 1 can be grouped according to Canter’s (2017) three components of kindness: benign tolerance; empathetic responsivity; and, principled proaction (see Method above). There are 14 acts in Table 1, with 4/7 in the top half being benign tolerance and only 1 being principled proaction, and 4/7 in the bottom half being principled proaction and only 1 being benign tolerance. Empathic responsivity is distributed almost equally between top and bottom. These results show that acts of cyber-kindness displaying benign tolerance are much more regularly performed than are acts of cyber-kindness displaying principled proaction. Presumably, this is because acts of benign tolerance are more easily achieved and more readily opportune than acts of principled proaction.

Transpersonal Identity

64% of respondents answer that they ‘regularly’ or ‘very regularly’ “When online I enjoy acting on behalf of people in need, regardless of their age, race, ethnicity, religion, or gender”, and 72% answer that they ‘never’ or ‘almost never’ “I act online as though the needs of other people are NOT as important as my own needs.” These results lend support to premise three that a transpersonal sense of identity may be a factor of cyber-kindness.

Digital Activism

Table 2 displays the results for the percentage of respondents who engaged in the forms of Internet activism previously surveyed in Klisanin’s (2012) earlier study of digital altruists and cyber-heroes.

The results reveal that individuals are highly engaged in creating or signing digital petitions, posting positive content online, and posting informational content online for the purpose of helping others and provide evidence for premise two that people engaging in cyber-kindness will expend effort. These findings replicate those of Klisanin (2012) with a different demographic and a larger sample.

Motivations for Cyber-Kindness

Table 3 ranks the motivations for performing acts of cyber-kindness. The results show that cyber-kindness is primarily motivated by other-oriented motivations, as the top four motivations are all directed at improving other people’s lives. The bottom three motivations, with low mean scores all below the mid-point on the scale, are all self-oriented motivations. The findings thus provide evidence for premise four that motivations for performing cyber-kindness will be prosocial and other-oriented.

Effort

Respondents were clearly disposed to putting some effort into their online kindness activities, with all five questions relating to expending effort in cyber-kindness scoring well above the mid-point of the scale (range of means = 3.14 to 3.83).

Relationship Between Online and Offline Kindness

Table 4 suggests that there is a relationship between online and offline kindness, such that there is contiguity between them. The highest scoring answers all suggest that kindness online extends to kindness in the real-world, and that online kindness can also have real-world effects, by helping improve lives offline and spreading good in society. By contrast, all the lowest scoring answers are those that posit a weak relationship between online and offline kindness.

Considered together, the results of this study provide strong evidence that cyber-kindness is widespread and frequently performed. Many different varieties of cyber-kindness activities are carried out, with acts of benign tolerance and empathic responsivity being the most frequent and widespread, and acts of prosocial proaction being the least so. A range of motivations seem to underpin cyber-kindness activities, yet they are overwhelmingly emotionally positive and other-oriented in nature. Further evidence was provided that a transpersonal sense of identity is a core feature of cyber-kindness practitioners. In addition, the relationship between online and offline kindness seems to be robust, with contiguity between the two arenas of kind activity, and little evidence of a substantial ‘slacktivism’ component to cyber-kindness.

Discussion and Conclusion

The present study has shown that cyber-kindness is a legitimate and widespread phenomenon. Whilst there has been societal concern over the prevalence of cyber-bullying (Kowalski, Limber, & Agatston, 2008), our results suggest that there are grounds for optimism too regarding human behavior in cyber-space and the future of the Internet. In many ways, this should not be a surprise, given that the Internet is the product of human endeavor and that it is a reflection of our shared human nature (Suler, 2016). Human kindness is highly prevalent in human affairs (Ricard, 2015) and therefore should be found in abundance online. Our research presents the first direct and substantial evidence of the pervasiveness of the phenomenon of cyber-kindness.

Whilst there has been a lack of empirical research into the structure and the different components of human kindness, a recent factor analysis by Canter et al. (2017) distinguished between three main aspects of kindness: benign tolerance, empathic responsivity, and prosocial proaction (described in the introduction above). The present study finds support for the prevalence of each of these components of kindness in cyber-space. Yet whilst all components were enacted, the results show that acts of cyber-kindness displaying benign tolerance are much more regularly performed than are acts of cyber-kindness displaying principled proaction. Presumably this is because benign tolerance is easier and more opportune than acts of principled proaction. Nevertheless, inspection of Tables 1 and 2 reveals that acts of principled proaction are nevertheless widely represented amongst cyber-kindness activities and forms of digital activism, which lends further support to the notion that ‘slacktivism’ is not the primary mode of online kindness. It is not currently known whether the frequency skew between benign tolerance and principled proaction of cyber-kindness reflects that of kindness in everyday human affairs, thus future research could explicitly explore this question.

Cyber-kindness performers appear to be motivated to carry out their actions for ‘other-oriented’ purposes. Personal gain or benefit seemed to play very little, if any, part in performing cyber-kindness, and the phenomenon looks as if it is driven by empathic, compassionate, benevolent, and altruistic dispositions. Respondents also answered that they are motivated to act to achieve higher aspirations of humanity, such as ‘promoting peace in the world.’ Collectively, this pattern of results supports Klisanin’s (2012) earlier finding that a transpersonal sense of identity facilitates digital activism, and empirically extends that conclusion to encompass proponents and performers of cyber-kindness too.

We also explored the relationship between online and offline kindness. To date, no empirical research has investigated the relationship between the full spectrum of online kindness and altruism and offline altruism and kindness. Bosancianu et al. (2013) report a positive correlation between online and offline prosocial behavior, with altruistic activities in their study that overlap with altruistic activities in the present study. However, their study does not explore the spectrum of acts included in our cyber-kindness activities and our acts of digital altruism. Moreover, our research does not correlate frequency of online and offline acts of kindness, but instead asks respondents to self-report on their subjective assessments of their behavior, and this does not serve as a direct test of the hypothesis. Nevertheless, although preliminary, the present research supports the notion that online and offline kindness are contiguous. Further work will need to investigate this relationship in more detail.

Three further limitations merit consideration. First, our sample is heavily and positively skewed towards females. Although gender differences in responses were typically very small, two were reported above as statistically significant. Both these items were related to empathy and compassion (to ‘compliment others’ and ‘comfort’ others who express sadness). Gender differences related to altruism and social Internet use were previously noted by Price, Leong, and Ryan (2005), however, the question of gender differences in altruism is a complex one (Andreoni & Vesterlund, 2001), and was beyond the scope of the present research. It may be the case that female cyber-kindness is more ably expressed in compassionate forms compared with males—this is an area ripe for future research.

The second concern for our study is that the sample was predominantly drawn from a population who had previously voluntarily signed up as a member of a kindness website (kindness.org). The membership is free, anonymous, and requires nothing of participants. It is not perhaps surprising that we found strong evidence of a range of cyber-kindness activities within this convenience sample. It is important to note that we are not suggesting that these findings can be generalized beyond our sample, although of course, we expect that cyber-kindness activities would be enacted by people drawn from more representative samples. Nevertheless, although our sample comprises kindness advocates, the primary purpose of our study was to explore whether people who show an interest in kindness also carry out acts of kindness in cyber-space, and to further identify what those acts are, which are the most prevalent, frequent and popular, and what motivates them. Our study has contributed useful knowledge in this regard. It will also serve as an important baseline study for subsequent statistical research. Future work on cyber-kindness could usefully include representative samples of the general population.

Third, there is the potential for social desirability bias to distort the results in the present study. Whilst the pattern of the data does not reflect the presence of a strong desirability bias (the most socially desirable cyber-kindness activities were not the most frequent, for instance), and though participants completed the questionnaire anonymously, there is still scope to reduce the possibility of bias and future work in this area should aim to do so.

Another important next step is to research the wider impact(s) of cyber-kindness (both online and offline). Bosancianu et al.’s (2013) study found that there is a relationship between online pro-social behavior and online social capital, but also that there may be some link between online prosocial behavior and offline social capital. It is too soon to draw any firm conclusions regarding the positive and/or negative effects of cyber-kindness, yet this is an area ripe for exploration. Given that the spread of prosocial behaviors is known to occur in social networks (Fowler & Christakis, 2010), we think it would be particularly interesting to empirically investigate the potential for cyber-kindness to spread throughout online social networks, and to permeate connected offline social networks. These ripple effects of prosocial activity may have significant positive effects on human wellbeing, as it is well-established that acts of kindness boost happiness and positive affect (Curry, Rowland, Zlotowitz, McAlaney, & Whitehouse, 2018).

This research supports previous research in digital altruism, as well as research indicating that Internet activism is not a form of slacktivism. On the contrary, it adds support to existing research suggesting that Internet activism can be so effective that it results in an heroic act. The findings lend further support to the cyberhero archetype and new forms of heroism that involve the use of digital technologies, e.g., collaborative heroism (Klisanin, 2017).

This study brings kindness more prominently into an important domain and broadens the ways we think about and consider positive online behavior. Cyber-kindness has been suggested by Cassidy et. al., (2012, 2013), as an antidote to cyberbullying, however as the Internet of Things (IoT) and artificial intelligence (AI) become ever more ubiquitous aspects of our lives, explorations of positive cyber activity are necessary, not only to combat negativity, but also to support human flourishing. Through continuing to research cyber-kindness, we may also enhance our capacity to design technologies that support a kinder society.

References

Andreoni, J., & Vesterlund, L. (2001). Which is the fair sex? Gender differences in altruism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(1), 293-312.

Bartlett, 2014. The Dark Net: Inside the digital underworld. London: Heinemann

Bosancianu, C. M., Powell, S., & Bratović, E. (2013). Social capital and pro-social behavior online and offline. International Journal of Internet Science, 8(1), 49-68.

Canter, D., Youngs, D., & Yaneva, M. (2017). Towards a measure of kindness: An exploration of a neglected interpersonal trait. Personality and Individual Differences, 106, 15-20.

Cassidy, W., Brown, K., & Jackson, M. (2012). “Making kind cool”: Parents’ suggestions for preventing cyber bullying and fostering cyber kindness. Journal of Educational Computing Research. 46(4), 415-436.

Cassidy, W., Brown, K., & Jackson, M. (2013). Moving from cyber-bullying to cyber-kindness: What do students, educators and parents say?. In Examining the Concepts, Issues, and Implications of Internet Trolling (pp. 62-83). IGI Global.

Curry, O. S., Rowland, L., Van Lissa, C., Zlotowitz, S., McAlaney, J., & Whitehouse, H. (2018, in press). Happy to Help? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of performing acts of kindness on the well-being of the actor. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology

De Waal, F. (2010). The age of empathy: Nature’s lessons for a kinder society. New York: Broadway Books.

Fatkin, J. M., & Lansdown, T. C. (2015). Prosocial media in action. Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 581-586.

Fowler, J. H., & Christakis, N. A. (2010). Cooperative behavior cascades in human social networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(12), 5334-5338.

Georgetown University’s Center for Social Impact Communication and Ogilvy Public Relations Worldwide. (November, 2011). Dynamics of cause engagement. Retrieved November 2017, from: http://www.slideshare.net/georgetowncsic/dynamics-of-cause-engagement-final-report

Gruber, H. (1997). Creative altruism, cooperation, and world peace. In M. Runco & R. Richards (Eds.), Eminent Creativity, Everyday Creativity, and Health (pp. 463-79). Greenwich, CT: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Internet World Stats. (2017). History and growth of the Internet from 1995 till today. Retrieved December 2017, from http://www.internetworldstats.com/emarketing.htm

Klisanin, D. (2011). Is the Internet giving rise to new forms of altruism? Media Psychology Review, 3(1), 1-11.

Klisanin, D. (2012). The hero and the Internet: Exploring the emergence of the cyberhero archetype. Media Psychology Review, 4(1).

Klisanin, D. (2017). Heroism in the networked society. Handbook of heroism and heroic leadership, 283-299.

Kowalski, R. M., Limber, S. P. and Agatston, P. W. (2008). Cyber Bullying: The New Moral Frontier, Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Oxford, UK. doi: 10.1002/9780470694176

Price, L., Leong, E., & Ryan, M. (2005). Motivations for social Internet use. ANZMAC Conference: Consumer Behavior. Edith Cowan University, Retrieved December 2017, from http://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworks/2507/

Ricard, M. (2015). Altruism: The power of compassion to change yourself and the world. London: Atlantic Books Ltd.

Rowland, L. (2018). Kindness – society’s golden chain? The Psychologist, 31, 30-34.

Sproull, L., Conley, C., & Moon, J. Y. (2005). Prosocial behavior on the net. The social net: Understanding human behavior in cyberspace, 139-161.

Sproull, L., Conley, C. A., & Moon, J. Y. (2013). The kindness of strangers: prosocial behavior on the Internet. The social net: Understanding our online behavior, 143.

Suler, J. R. (2015). Psychology of the digital age: Humans become electric. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Walsh, R. & Vaughan, F. (1993). “On transpersonal definitions”. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 25 (2) 125-182.