Study Of Consumer Attitudes Towards Psychopharmacological And Psychological Treatments For Mental Health Occurrences

Gage Stermensky II, M.A., & Peter Jaberg, Ph.D.

The School of Professional Psychology at Forest Institute

Abstract:

Abstract:

Objectives: The purpose of this study was to identify consumer knowledge and beliefs towards medical and mental health treatment providers and facilities, and how these attitudes and beliefs influence treatment decisions about pharmacological versus cognitive behavioral interventions for a fictitious disorder.

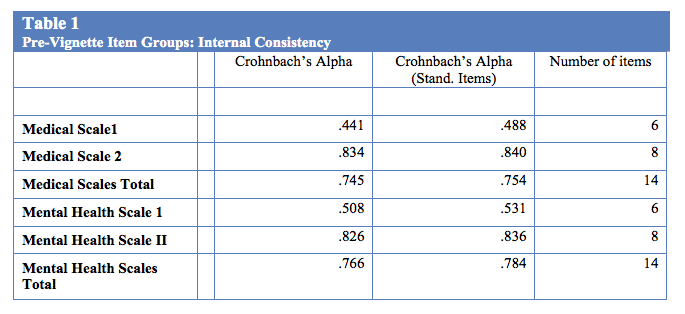

Methods: The researchers created a 67-item survey for the purposes of this study. The research questions, hypotheses, and current barriers identified in evaluating modern research on attitudes, stigmatization, and the like as related to treatment preferences among consumers guided survey construction. Following inclusion criteria validation, participants answered an attitudinal portion of the survey consisting of open and closed ended questions (coded for emergent themes by three independent coders) exploring opinions and experiences related to medical and mental health treatment (pre-vignette). Internal consistency was excellent for both the medical (α = 0.75) and mental health (α = 0.78) scales. Participants then viewed a randomly assigned vignette in an embedded video file with a post-vignette portion of the survey (Stermensky, 2011). Following observation of the randomly assigned vignette, participants completed the treatment preference survey based upon their understanding of Benson’s syndrome. The last section of the survey included demographic items.

Results: The researchers implemented paired t-tests to test statistical hypotheses regarding mean preference scores for section one (familiarity with facility resources and dimensions of care) and section two (ratings of personnel resources) medical and mental health scores (i.e., repeated measures). The mean medical prevignette preference score (M = 5.74, SD = 7.27) was significantly greater (t [123] = 1.87, p = < .001) than the mean mental health prevignette preference score (M = 3.87, SD = 7.27). These results suggest that participants overall had a more positive attitude towards medical treatment, staff, and facilities than for mental health resources (d = .26). Qualitative results supported the quantitative findings. Participants indicated an amplified level of trust and familiarity with medical treatment facilities. Participants also indicated side effects, effectiveness, and personal treatment views as deterrents for psychopharmacological mental health treatments.

Conclusions: Based upon these findings, it would seem the implementation of national advertising campaigns for evidenced based psychological practices would increase exposure and create a more informed consumer population. Whether health professionals, namely psychologists and physicians advertise jointly or separately, evidenced based information must be used to fully inform patients of their treatment choices, or else the adequacy of informed consent is being compromised at every level of care. The authors discuss implications for advertising, changes to direct to consumer advertising, and increasing public awareness of evidenced based practices in behavioral and psychological interventions.

Gage Stermensky II is currently a psychology fellow at the Gateway Foundation in Lake Villa, Illinois, doctorate student of clinical psychology at Forest Institute, and current faculty member at the University of Phoenix in Schaumburg, Illinois. He has over ten years of experience in behavioral healthcare working in various alcohol and drug, medical and mental health settings. He also has over four years of secondary education experience in medical, psychology, research, and human services course. Gage has successfully authored and chaired a community based healthcare grant for the American Heart Association, Blue Cross/Blue Shield, Southwest Minority Health Alliance, and the NAACP. Gage was also appointed to the NAACP health standing committee and Nebraska Region V social media task force.

Gage Stermensky II is currently a psychology fellow at the Gateway Foundation in Lake Villa, Illinois, doctorate student of clinical psychology at Forest Institute, and current faculty member at the University of Phoenix in Schaumburg, Illinois. He has over ten years of experience in behavioral healthcare working in various alcohol and drug, medical and mental health settings. He also has over four years of secondary education experience in medical, psychology, research, and human services course. Gage has successfully authored and chaired a community based healthcare grant for the American Heart Association, Blue Cross/Blue Shield, Southwest Minority Health Alliance, and the NAACP. Gage was also appointed to the NAACP health standing committee and Nebraska Region V social media task force.

Peter Jaberg is an associate professor at the School of Professional Psychology at Forest Institute and a part-time practitioner in Springfield, MO.

A Quasi-Experimental, Mixed Method Study Of Consumer Attitudes Towards Psychopharmacological And Psychological Treatments For Mental Health Occurrences

INTRODUCTION

Psychology and other mental health treatment services have negative connotations in American society, but going to one’s physician to receive treatment is more acceptable (Harkess & Bower, 2000; National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH], 2010; Spencer & Nashelsky, 2005). The reasons for this are comfort with one’s physician, media and cultural portrayals of mental illness, less stigma attached to “medicalized” issues, and awareness of benefits in seeking out medical professionals (APA, 2011; Conrad & Leiter, 2008; Payton & Thoits, 2011; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2010).

One social institution that appears to have had an effect on these views is direct to consumer advertising (DTCA; Lacasse, 2005; Timko & Chomky, 2008). Advertising of medications by pharmaceutical companies includes awareness of target and the US Food and Drug Administration approved symptoms that medications treat, federally mandated lists of side effects, and recommendations to contact their doctor (medical) to seek help for depression. This has led to an increase of a previously existing trend that mental health issues have been treated more frequently by physicians than mental health professionals (Harkness & Bower, 2000; Ledoux et al., 2009; Spencer & Nashelsky, 2005). Visits to physicians for depression resulted in an antidepressant prescription 87-89% of such visits in the U.S. (Stafford, MacDonald, & Finkelstein, 2001). Medicalization of society is highly influential in consumer treatment preference and treatment beliefs for a mental health occurrence by medical or psychological professionals, the efficacy of pharmacological or psychological interventions, and knowledge in treating mental health occurrences (Conrad & Leiter, 2008; Williams, Gabe, & Davis, 2008).

Ramifications of the increasing medicalization of mental health occurrences have led to increasing pharmacological sales, prescriptions written, and money spent on advertising (Clarke et al., 2003). Donohue, Cevasco, and Rosenthal (2007) identified an increase in advertising from 1996 ($985 million) to 2005 ($4 billion) of over $3 billion in advertising for pharmaceuticals, and overall spending increases from $11.4 to $29.9 billion for free samples, professional promotion, Pharmaceutical companies spent over $7 billion (nearly doubling DTCA costs [$4.2 billion] in 2005) marketing to physicians and other medication prescribers (Government Accountability Office, 2011; www.presciptionaccess.org, 2011). FDA allowance of DTCA has led to an increase in medications sales of almost 200% for adolescents, and between 1996 and 2001, 20% per year for adults (IMS, 2009; Schowalter, 2008; Timko & Chowansky, 2008). DTCA doesn’t have a safeguard for potential untoward influence of pharmaceutical company marketing on physicians and other prescribing clinicians. However, in light of no evidence to the contrary, it is assumed that prescriptions are made in an ethical and professionally competent manner. Therefore, how can marketing not have an effect on one’s views? Physicians (99%) and consumers (95%) both agree on one point: DTCA omits medication cost information (Frosch et al., 2010). In order to move towards a patient centered model of care, and not necessarily a pharmaceutical industry-driven model of distribution, integration of care represents the most comprehensive and ethical level of care for patients (Sammons, 2011; Smith, Giuliano, & Starkowski, 2011).

The increase in consumption of medications might reflect a variety of corporate and consumer preference trends. For example, the least amount of side effects has the strongest influence over consumer choice of treatment for mental health issues, and most consumers trust regulatory bodies, taking medications while uniformed of potential risks (Lacasse, 2005; Timko & Chomky, 2008). Furthermore, several researchers have argued that consumers lack the ability to effectively evaluate content found in varied DTCA (e.g., side effects, statistical claims, caveats and warnings) and consumers are more likely to spend more money on new, more expensive medications when generic or older medications with equal effectiveness are available (Donohue et al., 2007; Hollon, 2005; Lexchin & Mintzes, 2002, Lyles, 2002). Further, some authors claim that pharmaceutical companies have not fully communicated necessary information for consumers to make informed decisions that DTCA leads to increased pharmaceutical prices, and that impaired patient-physician relationships due to invention bias by patients (i.e., effects of medicalization of some behavioral health issues, leading to resistance to behavioral interventions) (Donohue, et al., 2007; Hollon, 2005; Lexchin & Mintzes, 2002, Lyles, 2002). Lastly, 23% of adults who have seen drug advertisements specifically asked their prescriber for the medications and 49% of physicians reported that they have felt “pressured” to prescribe a particular brand name drug (www.presciptionaccess.org, 2011).

Despite the popularity and ease of use of pharmaceutical interventions, behavioral interventions have the least amount of side effects, with many psychotropic medications having long lists of possible side effects (Antonuccio, Danton, & De Nelsky, 1995). How many psychologists have felt pressured to provide a particular treatment? Generally, it doesn’t occur. Patient pressure and requests for medications has a negative effect on physician and patient relationships, as well as effecting possible levels of trust between patients and physicians. Anxiety and depression account for the number one and number two (respectively) highest health care costs for employers, but percentage of benefits allocated to mental health coverage is less than 1% of employer health care plans in the U.S. (Clay, 2011). Clay (2011) further identifies the changes from fee-for-service programs to data-driven, outcomes focused care (which will require providers to prove their methods are effective).

Most literature for the treatment of depression indicates that psychological treatments can reduce the risk of long term symptom relapse more so than medications, and the most effective approach for the treatment of depression is a combination of psychological treatments and medications (Fava & Ruini, 2005; SIGN, 2010). Over-medicalization and disease stigma of mental health disorders likely impedes adoption of an integrated care model. However, physicians treating mental health occurrences most likely to make referrals to qualified mental health professionals only during initial assessment or crisis situations (Gerdes, Yuen, Wood, & Frey, 2001). Identifying ways to make the path to receiving mental health treatment easier to the general population through trust, awareness of evidence based practices, and information about cost-effectiveness will be essential in the future of affordable and realistic behavioral medicine (Thornicroft, 2008).

Current research does not address attitudes and beliefs of mental health consumers and related effects on the treatment preferences for behavioral or psychopharmacological interventions. By determining what role patient attitudes and beliefs play in the treatment patients seek, one may be able to better present the public with evidence-based practices in psychological treatments to treat patient mental health issues while providing care that results in fewer side effects. Implementation of patient centered medical home and health care reform will likely require careful consideration of patient perception and the development of integrated care models (Beacham, Kinman, Harris, & Masters, 2012; Miller & Kessler, 2011).

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effects of advertising content, treatment service provider, and the presentation of potential benefits and limitations of dual treatments on consumer preferences and perceptions. Participant attitudes and beliefs towards each treatment were recorded prior to vignette to obtain a baseline understanding of participant views. It was predicted that vignette viewership would determine participant treatment preference. The vignettes contained an actor portraying the providers, psychological treatment provider = psychological treatment preference, medical provider = medical treatment preference. Lastly, it was expected that participants would be more open to and supportive of pharmacological interventions (the likely result of previous exposure to DTCA) prior to viewing the vignettes.

METHODS

The researchers created a 67-item survey for the purposes of this study. The research questions, hypotheses, and current barriers identified in evaluating modern research on attitudes, stigmatization, and the like as related to treatment preferences among consumers guided survey construction. Following inclusion criteria validation, participants answered an attitudinal portion of the survey consisting of opinions and experiences related to medical and mental health treatment (pre-vignette). Internal consistency of the pre and post vignette scales is found in Table 1.

The pre-vignette items solicited general attitudes regarding mental health and medical treatments in the participant’s geographical area, factors that affect decisions in choosing health care providers and treatment, and information obtained from others regarding physical and mental health care treatment. Participants then viewed the vignette portraying a fictitious disorder, Benson’s Syndrome (see Stermensky & Jaberg, 2012 for more details) in an embedded video file. Following observation of the randomly assigned vignette, participants completed the treatment preference survey based upon their understanding of Benson’s syndrome. The last section of the survey included demographic items. Consent forms were distributed by Qualtrics technology to participants before accessing the research protocol.

PARTICIPANTS

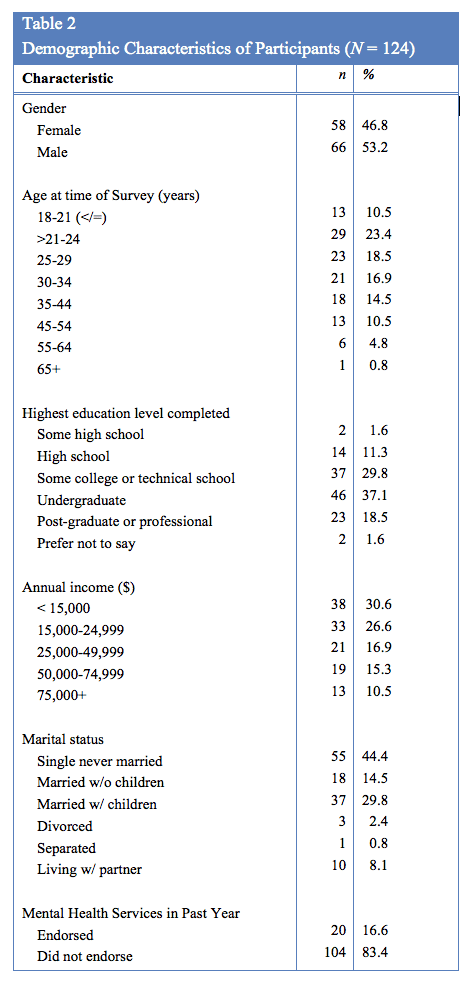

Of the 144 sets of responses initiated by respondents, 124 were used for data analysis and interpretation. The researchers eliminated responses from the data set from analysis because of: incomplete responses, missing responses, or because of a request to withdraw participation. The responses for those participants that completed their responses too quickly (e.g. less than the required minimum time needed to view the vignette, 1-2 minutes) were also removed from the data set. Table 2 summarizes participant demographic data.

RESULTS

The results include preliminary analysis of prevignette data (including cross-tabular analysis of prevignette variables by key demographic variables), post-vignette data results, and qualitative data results.

Medical and Mental Health Treatments for Mental Health Occurrences Prevignette Measures.

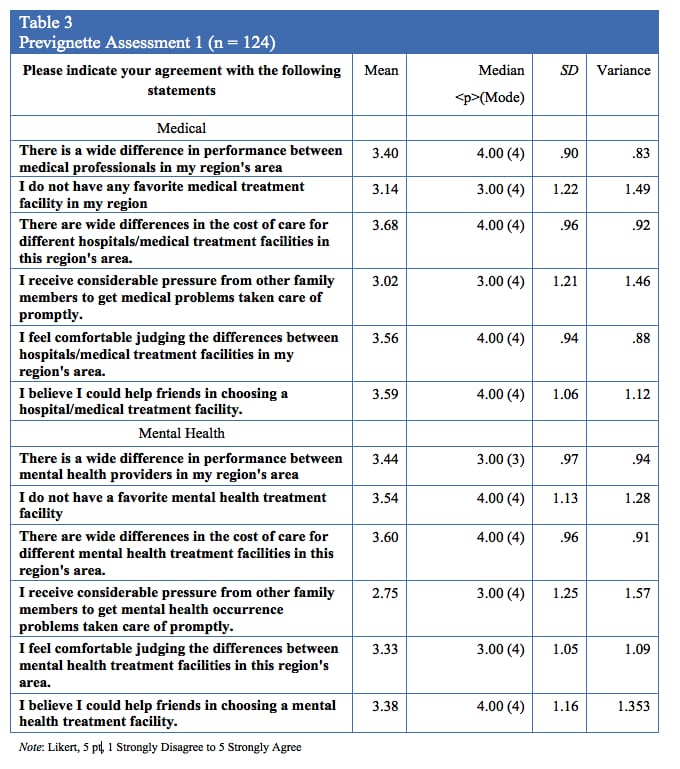

The researchers created frequency tables for both groups of prevignette items by totaling their scores for each category. Combining scores from section one and section two, and then dividing the total score by the number of questions in each section generated the scores (i.e., 14). Table 3 displays the results.

Preliminary analysis of prevignette data.

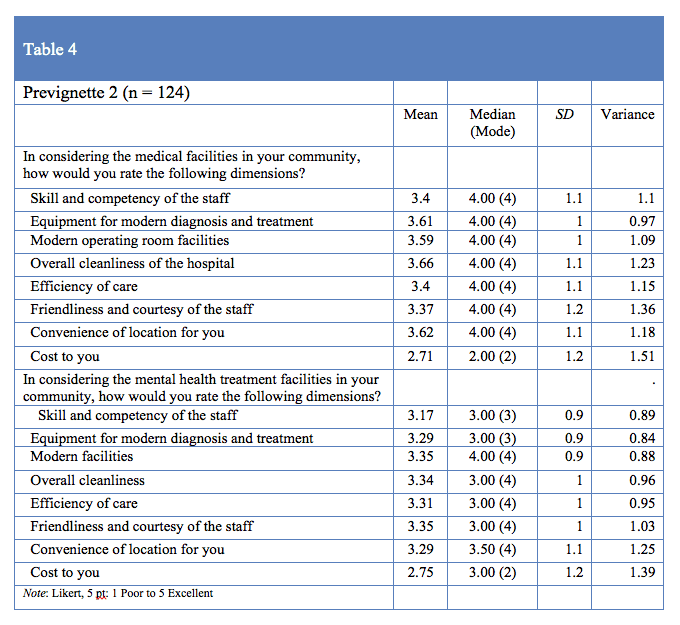

The prevignette portion of the study assessed the influence of current insurance status, beliefs about mental health treatment, familiarity with physicians, and possible stereotypes related to mental health and mental health treatment (e.g., indicating the medicalization of mental health occurrences). Observations for each participant were consistent with identified reports in the literature stating the general population has a limited understanding of mental health treatment facilities. This appeared to influence the development of ordinal-based rankings of medical and mental health facilities. The attitudinal portion of the survey observed participant’s overall attitudes towards mental health and medical treatment providers and facilities in participants’ local area both before and after viewing the randomly assigned vignette. The first portion of the survey queried overall knowledge and experience with both medical and mental health facilities in the participant’s area (Table 3). The second portion of the prevignette survey section focuses upon rating different aspects of each provider (Table 4).

The preference, attitude, and belief items included in both the prevignette and the post-vignette portion of the instrument included cost to you, overall skill and competency of staff, receiving family pressure to obtain services, and overall confidence in ability to choose a site based upon familiarity with each discipline (medical or mental health) in one’s geographical area. Overall, based upon observation of central tendency for individual prevignette items and combined categories, participants: a) had more knowledge and confidence in selecting medical treatment facilities (than mental health facilities); b) received family pressure to obtain medical services over mental health services; and c) were more likely to have a favorite medical treatment facility than a favorite mental health facility.

The authors implemented paired t-tests to test statistical hypotheses regarding mean preference scores for the section one (familiarity with facility resources and dimensions of care) and section two (ratings of personnel resources). The mean medical prevignette preference score (M = 5.74, SD = 7.27) was significantly greater (t [123] = 1.87, p = < .001) than the mean mental health prevignette preference score (M = 3.87, SD = 7.27). These results suggest that participants overall had a more positive attitude towards medical treatment, staff, and facilities than for mental health resources (d = .26). There was not a significant difference (p = .116) between mental health (M = 2.02, SD = 3.51) and medical (M = 2.39, SD = 3.25) prevignette ratings of familiarity with dimensions of care. The mean prevignette medical preference score for section two (M = 3.35, SD = 5.96) was significantly greater (t [123] = 1.51, p = <.001) than the mean mental health prevignette preference score for section two (M = 1.85, SD = 5.43; d = .26). Because there was a different pattern of results for section one and two, evaluating the mean scores for the overall combined preference did not significantly add to the interpretable data based upon the medical and mental health two (i.e., post-vignette) and total sections displaying identical effect sizes.

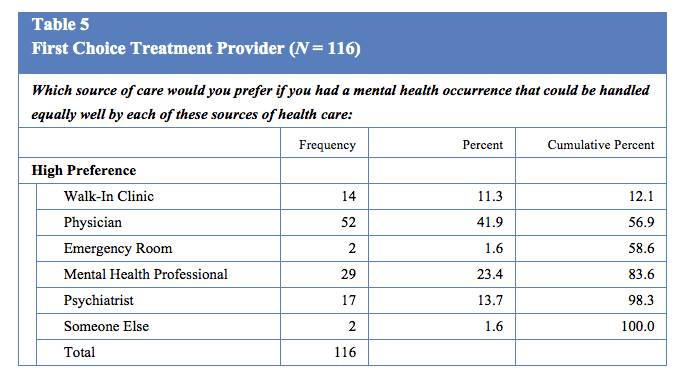

A final rank order question queried preferred treatment provider, if all providers could equally well treat mental health occurrences for the participant. The scale was based upon 1 = high treatment preference, 2 = second highest treatment preference, and so on, with 6 being the lowest rated individual or location. Table 5 lists the frequencies for the highest treatment preference.

Each participant’s current insurance/government assisted health care status, status as primary health care decision maker, and number of times a family member had received mental health treatment in the past three years were recorded to assess factors contributing to treatment decision making (psychological versus medical preference) of financial assistance to receive care. The frequencies for these variables indicate a majority of participants make healthcare decisions alone (n = 71, 57%) or jointly with a significant other (n = 42, 34%). Participants were equally represented by insurance status with 67 (54%) having some type of insurance or coverage and 57 (46%) reporting no current coverage. A majority of participants indicated receiving some type of medical services in the past three years (n = 104, 87%).

Qualitative Results

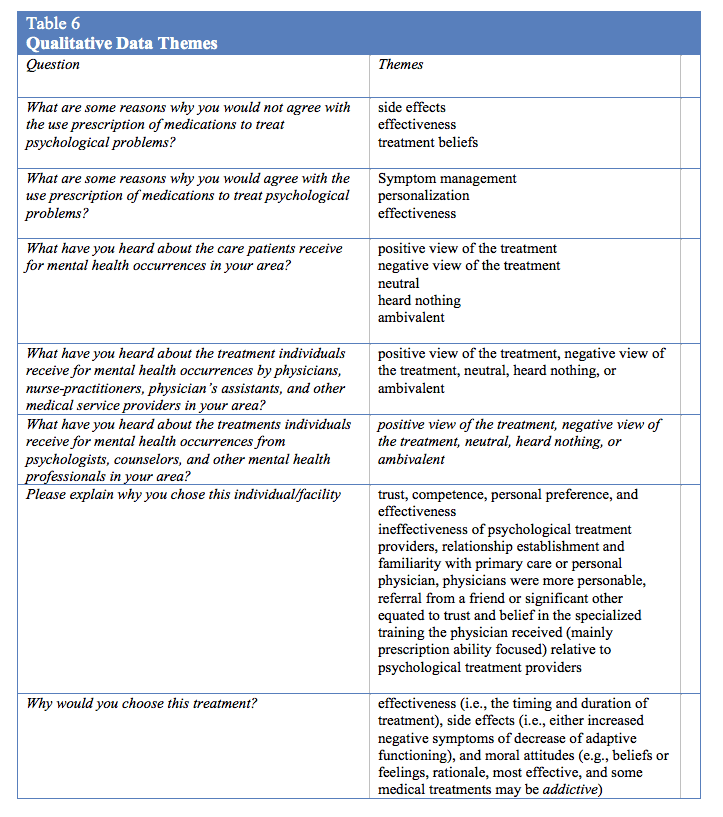

The researchers implemented open-ended questions throughout the survey to obtain subjective participant responses regarding their rationale for choosing different treatments, to explain their views towards both medical and psychological interventions to treat mental health occurrences, and to explain their preference for providers. That is, what factors influence a participant to demonstrate preferences towards medical or psychological treatments for mental health occurrences? Three independent coders viewed and coded each set of variables. Themes identified by the coders are listed in table 6.

Why would you choose this treatment? Although side effects, effectiveness, and moral attitudes emerged as the overarching themes of this question, various reservations about medical treatments, from either preconceived biases or video-vignette presented side effects, were apparent through the responses. The attribution of the medical treatment bias to decision making was more apparent in those participants who viewed the psychological vignette as opposed to those who viewed the medical vignette. The coders explored the influence of time and finances upon possible decision making of the participants. The coders reached a consensus of the overall focus of participants on side effects being a primary concern, but had discrepancies over the report of influence of time and financial aspects of the results. The coders reached a consensus that concern for costs and timing was present for many participants; however, these concerns were secondary to effectiveness and side effects. Participant perceptions indicated a severely flawed understanding of the role of psychological treatment providers and medical treatment providers, and may have influenced treatment preference for Benson’s Syndrome.

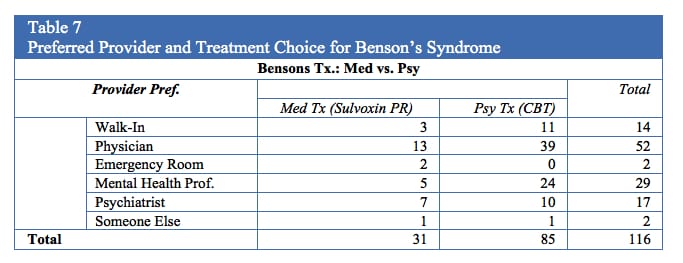

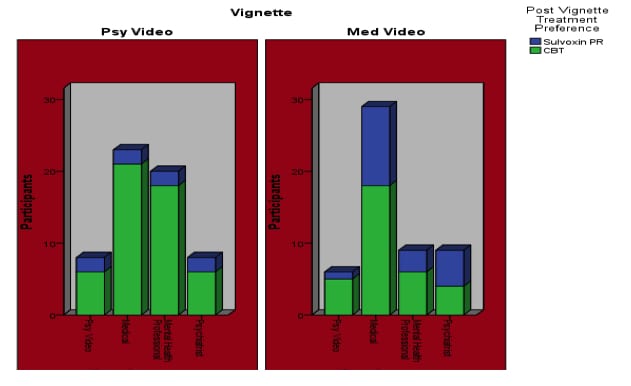

Regardless of participant perspective of effective treatment providers before viewing the vignette, the vignette influenced the reported qualitative information (i.e., in favor of psychological treatment). This leads to an interesting post hoc analysis of provider preference and ultimate selection of treatment. Although 52 participants indicated that they would prefer to seek services from their physician (prior to vignette), 39 of these individuals indicated their preference for CBT treatment with a psychologist (post-vignette) (Table 7) for Benson’s Syndrome. Figure 1 shows the dispersion of post vignette treatment preference based upon prevignette provider preference, Benson’s Syndrome treatment preference, and video the participant viewed. Comprehensive qualitative results are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Figure 1

Physicians were identified as the most preferred provider by participants (41.9%) followed by mental health professionals (23.4%) and psychiatrists (13.7%) for mental health occurrence treatment. When combining walk-in clinics (11.3%), emergency rooms (1.6%) with physicians, the total (61%) participants displayed a preference for medical facilities for the treatment of mental health occurrences. Participant’s qualitative responses most frequently cited trust, competence, personal preference, and effectiveness for all categories, but for participants that choose their physicians, trust was the most common theme. Interestingly, of 66 participants who indicated a physician or walk-in clinic as their mental health occurrence treatment preference, following exposure to the vignettes, 16 participants indicated a preference for medical treatment of Benson’s Syndrome, while 50 participants indicated a preference for the psychological treatment (i.e., desiring CBT treatment from their medical physician). Despite the positive influences of trust and familiarity for medical treatment, once presented with the side effects and outcomes of effectiveness for both treatments (psychological treatment vs. use of prescription medication), individuals indicated that CBT had fewer side effects and was more effective, and were willing to devote any amount of time necessary to the illness’s treatment. However, the influence of the infomercial and media appeared to create a change in treatment and provider preference among participants, despite initial trust and preference for physician treatment. Lastly, the two individuals who chose emergency rooms as their preferred treatment of mental health disorders endorsed Sulvoxin PR as their preferred treatment of Benson’s Syndrome.

Based upon qualitative data interpretation of reasoning for treatment choice, effectiveness (54%) and side effects (17%) were the most commonly endorsed reason for choosing the psychological treatment over the medical treatment, regardless of the preferred provider, video clip viewed, or any other variable, according to participants. However, the side effects were fabricated based upon common occurrences for SNRIs and CBT for depression and the side effects presented were identical in both vignettes. As such, it appears that trust in the provider and the provider’s ability to effectively treat their illness (based upon the information disseminated) is the main reason why participants were more or less likely to choose a certain treatment. Other reasons stated were distrust for medications as a whole, and that medications should be reserved for extreme circumstances (e.g., psychosis, impaired reality testing, mania).

The side effects for the CBT may be more significant than in realty, and if this is a determining factor to patients, it may be safe to assume that when presented with the actual side effects of psychological interventions versus pharmacological interventions, and the evidence supporting psychological interventions, the author believes the results would be even more strongly in favor of CBT.

Based upon these findings, it would seem the implementation of national advertising campaigns for evidenced based psychological practices would increase exposure and create a more informed consumer population. Whether mental health professionals, namely psychologists and physicians advertise jointly or separately, evidenced based information must be used to fully inform patients of their treatment choices, or else the adequacy of informed consent is being compromised. Furthermore, insurance companies are not honoring the spirit of regulations and laws pertaining to providing the best possible care, reimbursing more for medical treatments and interventions, even when comparable psychological treatments are supported by the same evidence, and providing coverage for an inadequate number of sessions. This further supports the need for brief therapies, concentrated psychological interventions carried out by highly trained and effective professionals, and the need for consumers to be better informed regarding the treatments they are receiving. Lastly, the ability to demonstrate treatment effectiveness should not only be a provider agency or third-party payer responsibility, but needs to become a systemic federal requirement (Clay, 2011).

Although in this study insurance status did not appear to be a major theme, access to appropriate and sufficient health care is a relevant current issue in the US. The disparity for mental health coverage has been apparent for some time, and regardless of the amount of literature and research in support of the effectiveness of mental health interventions, insurance companies do not provide appropriate resources for patient centers treatment featured integrated care opportunities. A more constructive solution may be to develop insurance guidelines that describe evidenced based practice guidelines across disciplines, and allow patients to make informed decisions about their treatment. A barrier to such cross-disciplinary standardization is likely opposing, and sometimes adversarial advocacy and lobbying that results in the fragmentation of mental and physical aspects of health and health care.

DTCA is also a system that needs many improvements. Given the apparent impact of advertising on perception and preference in this study, it is reasonable to speculate that pharmaceutical advertising, which is distributed more frequently and intensely than other evidenced based practices (i.e., dual therapy, exercise, and prevention programs), likely bias consumers to choose pharmaceutical interventions over other intervention options. To more fairly inform consumers regarding treatment options, implementation of financial limits to pharmaceutical-only advertising appears to be necessary. As suggested by Frosch et al. (2010), guidelines requiring longer commercials outlining side effects and appropriate usage, lack of distractions (i.e., music, reading side effects more rapidly than other information, ), and providing information on non-patented contemporary medications are necessary. Furthermore, the authors suggest DTCA for pharmacological interventions should be required to additionally provide information regarding research and evidence on psychological and combined psychological and pharmacological interventions in order to inform a vulnerable population about such a serious topic. This is not the equivalent of an infomercial explaining a hanging tomato planter, but serious medications that can cause lifelong alterations to one’s neurological and physical functioning. Furthermore, education of dual therapies and the current evidence based interventions that can be performed by psychologists, nurses, physicians, and nurse practitioners should be taught to children at an early age. Children do consume services, but they rarely get to make decisions. This will assist in current decision making ability, as well as an informed population of future health decision makers.

Limitations of the study included: internet based sample, complex stimuli (i.e., video stimuli with a male actor, which could have been represented in many different fashions), lack of ethnicity question in demographics, age disparity in participants, highly educated sample, lack of a previously established and studied outcome measure, participants self-reported their preferences in response to highly face-valid questions, and limited third party coding for qualitative data. In construction of the apparatus, in an attempt to gain a comprehensive picture of participants, their attitudes, and possible influencing factors, it appears that too many questions that were not relevant to the construct were included, and a more concise apparatus would have strengthened the precision and sensitivity of the study protocol. The rank order survey function was confusing to some participants, and lead to incomplete surveys or including their responses on the Mechanical Turk feedback page. Strengths of the study include: diversity in insurance coverage status, having a somewhat representative US sample, use of random assignment of participants to experimental stimuli, consistency in vignette scripts, robust main effects, and the apparent effective use of mild deception in attempts to minimize bias towards specific disorders or medications.

The present findings highlight the profound influence of media presentations on consumer treatment decision making for mental health occurrences. Furthermore, side effects, treatment effectiveness, and heightened levels of trust with physicians were also supported based upon the study findings. Costs, time of treatment, and insurance coverage were not found to be significant predictors of participant decision making. The implications for policy including possible amplification of mental health treatment advocacy efforts, which highlight psychological treatment effectiveness, as well as the evidence that supports dual treatment for many disorders, should be implemented at state and federal levels. Both medical and mental health professionals must also strive to ensure patients in both settings are educated and presented with sufficient information of the evidence of both pharmacological and psychological interventions in order to allow consumers to make informed decisions. Media presentations have an undeniable effect on consumer decision making, so possible reformulations of the DTCA laws and regulations need further exploration.

References

American Psychological Association. (2011). Your mental health: A survey of Americans understanding of the Mental Health Parity Law. Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Antonuccio, D. O., Danton, W. G., & De Nelsky, G. Y. (1995). Psychotherapy versus medication for depression: Challenging the conventional wisdom with data. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 26 (6), 574-585.

Beacham, A. O., Kinman, C., Harris, J. G., & Masters, K. S. (2012). The patient-centered medical home: Unprecedented workforce growth potential for professional psychology. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 43(1), 17-23. doi:10.1037/a0025320

Clarke, A. E., Shim, J. K., Mamo, L., Fosket, J. R., & Fishman, J. R. (2003). Biomedicalization: Techno scientific transformations of health, illness, and U.S. biomedicine. American Sociological Review, 68 (4),161–194.

Clay, R. A. (2011). The future of behavioral health care. Monitor on Psychology, 42 (5), 52.

Conrad, P. & Leiter, V. (2008). From Lydia Pinkham to Queen Levitra: Direct-to-Consumer Advertising and medicalisation. Sociology of Health and Illness, 30 (6), 825–838. doi: 10. 1111/j.1467-9566.2008.01092.x

Donohue, J. M., Cevasco, M., & Rosenthal, M. B. (2007). A decade of Direct-to-Consumer Advertising of prescription drugs. New England Journal of Medicine, 357 (7), 673–81.

Fava, G., & Ruini, C. (2005). What is the optimal treatment of mood and anxiety disorders? Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 12(1), 92-96. doi:10.1093/clipsy/bpi011

Frosch, D. L., Grande, D., Tam, D. M., & Kravitz, R. L. (2010). A decade of controversy: Balancing policy with evidence in the regulation of prescription drug advertising. American Journal of Public Health. 100(1), 24-32. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.153767

Gerdes, J., Yuen, E., Wood, G., & Frey, C. (2001). Assessing collaboration with mental health providers: The primary care perspective. Families, Systems & Health: The Journal of Collaborative Family HealthCare, 19(4), 429.

Government Accountability Office. (2011). Prescription drugs: Trends in usual and customary prices for commonly used drugs. GAO-11-306R. Washington D.C.: GAO.

Harkness, E. F., & Bower P. J. (2009). On-site mental health workers delivering psychological therapy and psychosocial interventions to patients in primary care: effects on the professional practice of primary care providers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1, CD000532. doi: 10.1002/14651858

Hollon, M. F. (2005). Direct-to-Consumer Advertising: A haphazard approach to health promotion. Journal of the American Medical Association, 293 (16), 2030–2033.

IMS Health. (2009). IMS Health National Prescription Audit. Retrieved from http:// www.imshealth.com/portal/site/imshealth/menuitem.a46c6d4df3db4b3d88f611019418c22a/?vgnextoid=85f4a56216a10210VgnVCM100000ed152ca2RCRD&cpsextcurrchannel=1

Lacasse, J. (2005). Consumer advertising of psychiatric medications biases the public against nonpharmacological treatment. Ethical Human Psychology and Psychiatry. 7 (3), 175-179.

Ledoux, T., Barnett, M., Garcini, L., & Baker, J. (2009). Predictors of recent mental health service use in a medical population: Implications for integrated care. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 16(8), 304-310. doi: 10.1007/s10880-009-9171-x

Lexchin, J. & Mintzes, B. (2002). Transparency in drug regulation: Mirage or oasis? Canadian Medical Association Journal. 171(11):1363-1365. doi:10.1503/cmaj. 1041446

Lyles, A. (2002). Direct marketing of pharmaceuticals to consumers. Annual Review of Public Health. 23, 73–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.23.100901.140537

Miller, B. F., Kessler, R., Peek, C. J., & Kallenberg, G. A. (2011). A National Agenda for Research in Collaborative Care: Papers from the Collaborative Care Research Network Research Development Conference. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 2011.

National Institute of Mental Health. (2010). Statistics on Mental Health. Baltimore, MD: Department of Health and Human Services.

Payton, A. R. & Thoits, P. A. (2011). Medicalization, Direct-to-Consumer Advertising, and mental health stigma. Society of Mental Health. 1 (55), 56-70. doi: 10.1177/2156869310397959

Sammons, M. T. (2011). Can prescribing psychologists assist in providing more cost-effective, quality mental healthcare?. In N. A. Cummings, W. T. O’Donohue, N. A. Cummings, W. T. O’Donohue (Eds.), Understanding the behavioral healthcare crisis: The promise of integrated care and diagnostic reform (pp. 129-148). New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor, & Francis Group.

Showalter, J. E. (2008). How to manage conflicts of interest with industry? International Review of Psychiatry. 20 (2), 127-133. doi: 10.1080/09540260801887728

SIGN (2010). Non-pharmaceutical management of depression in adults: A national clinical guideline. Edinburg: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Retrieved from MEDLINE with Full Text database.

Smith, M., Giuliano, M. R., & Starkowski, M. P. (2011). In Connecticut: Improving patient medication management in primary care. Health Affairs, 30(4), 645-654. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.201l.0002

Spencer, D. C., & Nashelsky, J. (2005). FPIN’s Clinical inquiries: Counseling or antidepressants for treating depression? American Family Physician 72 (11), 2309-2310.

Stermensky, G. (2011). A comparative study of attitudes towards psychopharmacological and psychological treatments: Effects of provider recommendation. PsyD/ M.A. Thesis. The School of Professional Psychology at Forest Institute: Springfield, MO.

Stermensky, G., & Jaberg, P. (2012). Psychopharmacology vs. Psychological treatment for behavioral issues: Consumer preference based upon provider recommendation. Society of Behavioral Medicine Rapid Communications: Engaging New Partner & Perspectives (33), 11.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2010). Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Mental health findings. Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH. Series H-39, HHS Publication No. SMA 10-4609. Rockville, MD.

Thornicroft, G. (2008). Stigma and discrimination limit access to mental health care. Epidemiologia E Psichiatria Sociale, 17(1), 14-19.

Timko, C. A., & Chowansky, A. (2008). Direct to Consumer Advertising of psychotropic medication and prescription authority for psychologists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, Vol. 39 (5), 512-518. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.39.5.512

Williams, S. J., Gabe, J., & Davis, P. (2008). The sociology of pharmaceuticals: progress and prospects. Sociology of Health and Illness, 30 (6), 813–824. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2008.01123.x

www.presciptionaccess.org. (2011). Prescription access litigation project. Retrieved from www.prescptionaccess.org.