Cognitive Psychology and the Small Screen

Bonnie Buckner

President, MicroFocus Media

Abstract:

Technology is increasingly smaller and mobile. Such confines present challenges in how the material transmitted on this technology is consumed by the end user.Cognitive psychology examines information processing and offers insight into how to overcome these challenges. In this paper I will explore principles of cognitive psychology that can be useful guides in considering the production of material for the small screen.

Bonnie Buckner has over fifteen years experience in the entertainment industry, featuring a combination of sales, marketing, management, technology related business solutions and entrepreneurial experience. Buckner began her career in syndicated television sales rising to the challenges of leadership responsibilities and managerial posts that led to the founding of two successful development companies. This wide spectrum of roles has enabled her to move easily from the front lines to the boardroom, where Buckner focuses on marketing and leadership, with a big-picture view of company formation and problem solving. In 2004 Bonnie co-founded Media Vote, Inc., provider of micro-targeting and competitive research data for marketing and image campaigns. Buckner’s various roles in film and television–producing a documentary, syndicated television sales, film development and freelance writing–her work with MicroFocus Media/Media Vote, and her involvement in projects that work closely with city programs and grassroots organizations for neighborhood improvement come together in her research focus. Bucker’s research explores the use of imagery at the corporate and personal level with the goal of bridging gaps of communication between the two. bonnie@microfocusmedia.com

Bonnie Buckner has over fifteen years experience in the entertainment industry, featuring a combination of sales, marketing, management, technology related business solutions and entrepreneurial experience. Buckner began her career in syndicated television sales rising to the challenges of leadership responsibilities and managerial posts that led to the founding of two successful development companies. This wide spectrum of roles has enabled her to move easily from the front lines to the boardroom, where Buckner focuses on marketing and leadership, with a big-picture view of company formation and problem solving. In 2004 Bonnie co-founded Media Vote, Inc., provider of micro-targeting and competitive research data for marketing and image campaigns. Buckner’s various roles in film and television–producing a documentary, syndicated television sales, film development and freelance writing–her work with MicroFocus Media/Media Vote, and her involvement in projects that work closely with city programs and grassroots organizations for neighborhood improvement come together in her research focus. Bucker’s research explores the use of imagery at the corporate and personal level with the goal of bridging gaps of communication between the two. bonnie@microfocusmedia.com

Relevant Concepts in Cognitive Psychology

Cognitive psychology is the area of psychology that explains the processes by which we make sense of our environment. Specific processes described by cognitive psychology include: “attention, perception, learning, memory, language, problem solving, reasoning and thinking (Eysenck, 2001, p. 1).” It is by these processes that human beings perceive, analyze and explain their experiences, solve problems and determine actions (Eysenck, 2001).

Approaching small screen production requires more than simply scaling down a visual display, whether web page, powerpoint, or movie. Because the size and amount of available visual information is reduced, and the often distracting and attention-demanding settings in which small screen productions are viewed – such as watching a DVD on a laptop in an airport – there are more challenges to our ability to perceive and comprehend information on a small screen. Thus, an understanding of some principles of how we process information provided by cognitive psychology can aid in creating successful small screen productions, whether they be informational or entertainment focused.

Beginning with a broad view, information processing from the perspective of the cognitive psychologist explains that information from the environment moves through a series of processing systems; such as, attention, memory and perception (Eysenck, 2001). These processing systems then digest the information, transforming it into useable material (Eysenck, 2001). This processing occurs in observable, systematic ways (Eysenck, 2001).

Earlier versions of information processing argued that it occurred in the following sequential chain: stimulus-attention-perception-thought processes-decision-response or action (Eysenck, 2001). This was referred to as bottom-up processing, which also stated that the processes occur one at a time, also known as serial processing (Eysenck, 2001). Now it is known that information also follows top-down processing which is “influenced by the individual’s expectations and knowledge rather than simply by the stimulus itself (Eysenck, 2001, p. 2). Usually information is processed via a mixture of the two sequences (Eysenck, 2001). Additionally it is known that processing is parallel, meaning that multiple processes act simultaneously (Eysenck, 2001).

Earlier versions of information processing argued that it occurred in the following sequential chain: stimulus-attention-perception-thought processes-decision-response or action (Eysenck, 2001). This was referred to as bottom-up processing, which also stated that the processes occur one at a time, also known as serial processing (Eysenck, 2001). Now it is known that information also follows top-down processing which is “influenced by the individual’s expectations and knowledge rather than simply by the stimulus itself (Eysenck, 2001, p. 2). Usually information is processed via a mixture of the two sequences (Eysenck, 2001). Additionally it is known that processing is parallel, meaning that multiple processes act simultaneously (Eysenck, 2001).

Taking a look at visual perception, we can say, then, that it is both stimulus-response (bottom up) and influenced by the individual’s expectations and knowledge rather than by the stimulus itself (top down). Constructivist theorists in cognitive psychology emphasize top-down processes in visual perception (Esyneck, 2001). Their school of thought makes the following assumptions (Esyneck, 2001, p. 27):

1. Perception is an active and constructive process.

2. Perception occurs as the end-product of the interactive influences of the presented stimulus and internal hypothesis, expectations, and knowledge, as well as motivational and emotional factors.

3. Perception is influenced by hypothesis and expectations that are prone to error.

Applying Visual, Audio, and Linguistic Cognitive Concepts to Small Screen Production

Visual perception as determined by constructivist memory.

Applying these concepts to small screen production, as an audience we draw from a learned body of knowledge of media to add to, or piece together, our experience of a production. We not only take in at face value the visuals presented to us, we anticipate, and are motivated to suspend disbelief and experience the events promised of the producer. An Indiana Jones film pledges adventure; a POV from the rider of a horse galloping at full speed provides us this vivid thrill. Today’s western film audience has grown with the medium. Together, medium and audience have refined this language such that audience members approach films understanding their sentences, their diagrams, the sequences they use to fabric story. We are cued by a title, a genre, setting, music and dialogue in addition to visuals to form our expectations of what we are viewing, and as such our experiences. Gregory describes perceptions as “constructions from floating fragmentary scraps of data signaled by the senses and drawn from the brain memory banks, themselves constructions from the snippits of the past (1972, as quoted by Esyneck, 2001, p. 27).” Two lovers catching sight of each other across the room tell us a meeting is imminent; armies mounting their horses signal a battle. We’ve seen these events, and the memory of them prompt us to visualize them again given familiar sequences.

Constructivist assumptions of visual perception are exemplified in the evolution of battle scenes from Gone with the Wind, produced in 1939 for the big screen, to Glory produced in 1989 for television, wherein wide static camera placement that recorded the entire battle from a distance became medium-shots much closer to the action.

Even further, the battle scenes in Henry V (1989) are composed primarily of extreme close-ups of disparate images – a wagon wheel churning in the mud, a grimy arm gripping a sword, blood dripping. And yet, when we watch Henry V we are watching a full battle scene. Our heart beats more quickly, our eyes widen and we are drawn into the action of battle. We have an expectation of the sequence of events. Our hypothesis are prone to error – we see a sword whipping across a soldier’s chest when in fact only an arm holding a bloody sword is shown and cut away from quickly. No longer is a fixed and whole depiction necessary; fragments are pieced together to create a holistic experience as intended by the filmmaker.

Audio perception and situated cognition.

Audio operates under much of the same perceptual processes as visual perception, subject to memory and expectation. As such, audio is an equally important piece in providing emotional influence and cues to guide our perceptions of a production. In addition, audio use can be informed by an understanding of affordances. Affordances describes our perception of an object as based upon the use it provides; for example, we understand a chair as something on which we sit, thus the materials used to build the chair and its design can alter without a loss of understanding that the resulting object is a chair (Gibson, 1979 as cited by Eysenck, 2001). In film as example, we are all familiar with the feeling elicited by the jarring discord in horror soundtracks, the increase in pace and rhythm that mirrors our own elevated heart rate. The music readies us to believe in the action, to accept that the rapid sequence of tombstones to the flitting of ragged wing to the pulsing of vein on alabaster neck is in fact a vampire attack. We piece these scenes together on the bridge of the music, carried by the affordance of the film genre, in this case a horror film.

As much as music acts as emotional influence, it is also context and cue: in the horror film example, the faster the rhythm and the higher in scale the notes, the closer we are in story to a climactic and horrific event. Context increases our ability to understand presented information. Palmer found that individuals identified objects correctly more often when presented in appropriate context than when presented in the wrong context or in no context at all (1975, as cited by Esyneck, 2001, p.27). The movie Amadeus (1984) provides an eloquent use of music as a contextual agent. Mozart skips a busy street with a carnival air whistling along to the bright composition we hear played as soundtrack by full orchestra. He bounds through a door, leaving it swaying open in his glee. A few more jaunty steps and he barrels through another door and stops short, mouth agape: the major keys turn to minor, the music ominous and dark. The camera reverses and we see Mozart’s POV, a dark, foreboding figure in black cape standing in a shadow at the top of the stairs. The next beat Mozart exclaims, “Papa” and races to the figure where he is engulfed in the black cape, the music hanging on minor note. The audience is cued emotionally to the awe inspired in Mozart by the father with the minor key. In addition, by presenting the father in this fashion Mozart’s bright “Papa” is out of context. This discord of information echoed by the music tells us that Papa is not exactly the man we have seen through Mozart’s eyes. Looking past the adored figure painted by Mozart we search for layers, and later are gratified when we experience the dark opera, Don Giovani, composed by Mozart after his father’s death. With one, elegant shift in note we learn information about two major characters and their relationship, we experience a change from one act to another, we are signaled portend, and we feel the over-arching theme for the film: that Mozart experiences people as notes – his music is a representation for his own life perception. One note tells us this wealth of information, without a single line of exposition.

Audio can also be used a tool to situate the audience in a particular environment or context. Situated cognition argues that knowledge is an integral part of the culture in which it is used – we understand an object and its use when learned in the environment in which it is used (Brown et al, 1989). National Public Radio employs this concept. Often their feature pieces are produced such that seconds of audio precede the journalist’s first words of the story. A rustle of leaves in a gentle breeze places us in neighborhood before a story about a building project. The sound conjures tree-lined sidewalks and front yards; we see an American suburb. When the journalist’s voice finally pierces the background as an audience we are there at the site. When her story unfolds about a subdivision built in Afghanistan the rustling leaves that continue beneath the words of the story keep us present to the information as we reconcile the unexpected. Because we have a knowledge of neighborhoods, this new introduction of a neighborhood development in a war-ravaged country is situated by the simple sound of trees swaying in the wind. The story provides context at three levels: place, theme and position. Images leap to our mind. Pylyshyn advocates that imagery are “top-down projections from higher cognitive systems (2003, p. 115).” The images that we see when we hear the rustling leaves are influenced by our own knowledge of neighborhoods, associated experience, beliefs and projections, which in turn help us to make sense of, and assimilate, the initially incongruous information in the story.

The NPR audio techniques that situate the listener via the images they evoke are augmented by another aspect of cognitive psychology which is the memory enhancement quality of pictures. Allport and his colleagues found that memory improves when the material is presented as visuals (1972, as cited by Eysenck, 2001, p. 131). NPR does not have the luxury of visual images; therefore it creates them in our mind. We see the trees lining the street and can imagine the creation of a neighborhood. Later when we hear the story takes place in Afghanistan we transport these images to the dusty terrain. Our attention to the story is increased, our memory of the information enhanced.

Memory is a sought-after resource. According to Miller the amount of characters that individuals can hold in their short-term memory is “seven, plus or minus two (1956, as quoted by Esenyck, 2001, p. 161). Miller found that this span does not necessarily refer to seven individual letters, but rather what he considered “chunks (1956, as quoted by Esenyck, 2001, p. 161). A logo consisting of numerous letters, such as Coke, is seen as only one chunk for those who know the logo, lending truth to the adage of a picture being worth a thousand words. Those very images increase our ability to process information. Pylyshyn tells us that we solve geometric problems by imagining the object which allows us a greater range of approach than if we were to “think in words (2008, online download p. 3).” Edward Tufte is a Harvard professor renowned for his work in visual displays of graphical information and statistics, quoting Philip Morrison to deem it “cognitive art (1990, introduction).” For Tufte, this art leaps off the page to sew informational pieces into an understood tapestry of information. He points us to Galileo’s published discovery of Saturn, wherein in the midst of the descriptive text Galileo free-hand drew the planet’s shape as he saw it through his spy-glass (Tufte, 1990). In Tufte’s words, “The stunning images, never seen before, were just another sentence element. Saturn, a drawing, a word, a noun (1990, p. 121).” Saturn, contextualized, attended to and remembered.

Linguistic concepts and the perception of visual image.

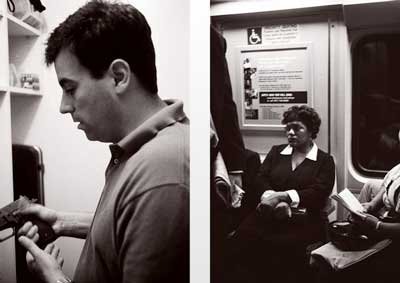

A related field within cognitive psychology is cognitive linguistics, which studies concepts as components of thought, and the cognitive processes surrounding these concepts (Lakoff, 2002). These concepts are often expressed through metaphors, which are used to frame our experiences (Lakoff, 2002). These metaphors present themselves as language and as images (Lakoff, 2002). Consider the image presented in a photograph by artist Juliette Hermant of the intimate profile of a Caucasian, clean-cut young man in his home holding a gun. This image will engender different metaphors in individuals depending on their backgrounds. A person raised in the Midwest on a farm will perhaps experience this image as informational – the man is pointing to the gun and perhaps explaining a particular aspect of it – another person sees a simple portrait. Now see the image in its full installation by the photographer, paired with the photo of an African American woman in a business suit on a crowded metro train. The metaphor shifts. Next we read the title of the installation: “Washington, DC.” Two images and one city name explode in us giving context and meaning to a comment on class, race and politics. The images are a metaphor for the artist about a particular aspect of American society; their juxtaposition brings forward our own metaphors for how we experience this aspect. And, perhaps more interestingly, these two images and one city name begin a dialogue, asking a question, leaving us to ponder the deeper meaning of their composition.

(Photo: “Washington, DC” by Juliette Hermant)

Production is not merely images and audio, it is text and dialogue. Language crafts metaphor. It cues us, provides context and provokes images, even teasing forth the memory of sounds and smells that we experience within. The following excerpt is from the beginning pages of Salmon Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children (1981):

Production is not merely images and audio, it is text and dialogue. Language crafts metaphor. It cues us, provides context and provokes images, even teasing forth the memory of sounds and smells that we experience within. The following excerpt is from the beginning pages of Salmon Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children (1981):

“The world was new again. After a winter’s gestation in its eggshell of ice, the valley had beaked its way out into the open, moist and yellow. The new grass bided its time underground; the mountains were retreating to their hill-stations for the warm season. (In the winter, when the valley shrank under the ice, the mountains closed in and snarled like angry jaws around the city on the lake.”

With Rushdie we emerge like baby chicks into his world of springtime, smelling the crisp remnants of winter, seeing the mountains surrounding the icy lake. We are placed, in just a few sentences, in Kashmir, at season’s turn, with all the anticipation of a story’s beginning before us. We are placed within the character himself, experiencing his world as he does.

Conclusion

Taken together the three production elements of visuals, audio and language, harmonize in a symphony of three-dimensional experience in an audience. In the movie Amadeus(1984)we are surrounding by the explosive colors of the courtesan life in which the movie takes place, our ears filled with the music of the composer and an eloquent language that tells a story rich with metaphor. In an anguished confession Salieri grieves his mediocrity and the conflicting pain of hating Mozart while simultaneously inspired by him. Salieri: “I was staring through the cage of those meticulous ink strokes at an absolute beauty.” Salieri speaks and across his face we see the musical score caging him in, creating a prison of jealousy and regret.

For the producer, small screen production calls for creativity in working with the elements of text, visuals and audio to expand beyond the confines of technology. Carefully considered, these elements enhance our ability to process information, increasing our perception, attention to and memory for the material. Working with these elements of production through the lens of cognitive psychology concepts helps to ensure that the pieces created have their intended effect, and that the audience’s experience is complete.

References

Brown, J.S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher: January-February, 32-42.

Brugge, P.J., & Fields, F. (Producers) & Zwick, E. (Director). (1989). Glory [Motion picture]. United States: Tri-Star Pictures.

Eysenck, M.W. (2001). Principles of Cognitive Psychology. Psychology Press, Ltd. Taylor and Francis Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

Hermant, J. (2006) Washington, D.C. DIY Gallery exhibit.

Lakoff, G. (2002). Moral Politics. University of Chicago Press. Chicago, Ill.

Pylyshyn, Z. (2008). Is the imagery debate over? If so, what was it about? [Electronic version]. Rutgers Center for Cognitive Science.

Pylyshyn, Z. (2003). Return of the mental image: Are there really pictures in the brain? [Electronic version]. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7(3), 113-118.

Rushdie, S.(1981). Midnight’s Children. London, Jonathan Cape.

Selznick, D.O. (Producer) & Fleming, V. (Director). (1939). Gone with the Wind [Motion Picture]. United States: MGM.

Sharman, B. (Producer) & Branagh, K. (Director). (1989). Henry V. [Motion Picture]. United Kingdom.

Tufte, E. (1990). Envisioning Information. Graphics Press, LLC. Cheshire, Connecticut.

Zaentz, S., Ohlsson, B., & Hausman, M.(Producers), & Forman, M. (Director). (1984). Amadeus [Motion picture]. United States: Orion Pictures.

—

Movie clips from YouTube:

Gone with the Wind http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gRnmWxBLtyM

Amadeus http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H3nqiKzB5fs

Henry V http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R98H2E9JWuY