What is Media Psychology? A Qualitative Analysis

Pamela Rutledge, PhD

Director, Media Psychology Research Center

ABSTRACT:

ABSTRACT:

Media psychology is a new academic and applied discipline emerging in response to the proliferation of communication technologies in the last fifty years. While there is much interest in the field, there is little agreement in defining media psychology. In response to this situation, a research team formed in July 2007 to investigate the perceptions of media psychology and establish a working definition. As a starting point, the researchers began by surveying APA Division 46 for Media Psychology, whose members were pioneers in the field, and could help identify emerging trends in a historical perspective. This paper discusses the qualitative analysis of Division 46 member responses to the question: “What Comes to Mind When You Think of Media Psychology?” and examines the Division 46 website to see if the website reflects the members’ responses.

Using a grounded theory approach, analysis showed that member responses focused on the human factor over technology. The emerging themes revealed a dichotomy among members between two different views of media psychology: 1) psychologists who use media to disseminate psychology information, and 2) using psychology for the analysis of media use, development, and application. The differences in perceptions were correlated with the age of the respondents; older members were more likely to subscribe to the view of a psychologist or psychological material in the media and the younger demographic was more likely to see psychology as a tool for analysis and development. In comparing the Division 46 website analysis to the member responses, the content was more consistent with the view of older members. Media effects and impact was a frequent response, however the data left unanswered questions about the respondents’ perception of agency relative to media, i.e. whether individuals and society are perceived as victims of media’s influence or interactive participants. Both areas will be important for further study as they hold implications for areas such as education, healthcare, and public policy.

Introduction

The last half-century of changes in media and communications technologies are transforming individual lives, popular culture, and global economics relations. Public and academic recognition of the integration of media into daily life has reached a critical mass, and the demand across society for an understanding of how to think about the things they see, hear, and use every day is widely apparent. Media psychology is the result. Some view the official emergence of media psychology as a separate field with the creation of the Media Psychology Division 46 in the American Psychological Association (APA) in the 1980s (Fischoff, 2005). An exact definition of media psychology is a work in progress because media technologies change so rapidly and there has been so little agreement within the field as to breadth and depth of its scope (Giles, 2003). This is illustrated by periodic suggestions to rename Division 46 to reflect the changing field of media psychology (e.g., Spielberger, 2006). An APA Division 46 study by Luskin and Friedland (1998) took a preliminary step in defining the field by polling practitioners and experts. The Luskin and Friedland study had two main objectives: (a) to develop a current list of media psychology applications and (b) to determine the importance of a grounding in psychology to the execution of those applications. However, even in the short time since the Luskin and Friedland study, technological advances have materially changed the media environment.

While there is little agreement as to the exact definition of media psychology, there is widespread agreement that a better understanding of many aspects of the field is critical. The new complexities of media ethics (e.g., Diesch & Caldwell, 1993), media perpetuation of stereotypes (e.g., Chafetz, Holmes, Lande, Childress, & Glazer, 1998; Coltrane & Messineo, 2000; Prabu David, 2002; Stern & Mastro, 2004), the implementation of distance learning programs (e.g., Rudestam, 2004), the use of the internet for health education (e.g., Cline & Haynes, 2001), and interactive educational tools in the classroom (e.g., Amory, Naicker, Vincent, & Adams, 1999) are among many areas where psychologists contribute critical skills and expertise. Some argue that academics need to expand research to include a broader view of media as it impacts individuals and social constructs (e.g., Fischoff, 2005; Rutledge, 2007). There are new academic programs integrating media and psychology, new journals dedicated to media psychology scholarship, and new career opportunities to answer the increasing demand in research (Oliver, Shrum, & Vorderer, 2006) and practice (B. Luskin, 2002).

Media psychology applications cover a broad range; there is almost no facet of life untouched by communications technologies (Rideout, 2007). Yet in the journal Media Psychology, content analysis shows that the preponderance of research examines effects and interactions with a narrow field of media psychology: media violence, media effects on children and adolescents, and media stereotypes (Derwin, de Merode, & Shayne, 2006). The disparity between the extensive range of applications and the limited focus of research indicate a need for an expanded definition and awareness. To promote the field in and out of academia, a clear statement of the breadth and significance of media psychology’s applications is necessary.

To answer this need, the research team began an exploratory study to better understand current perceptions in the field and take the first steps toward creating a current definition of media psychology.

Participants and Procedure

Because of their roles as pioneers in the field, members of APA Division 46 were selected as the sample population. Researchers felt this population might highlight emerging trends and current practical challenges in the context of historical perspective. With permission from Division 46 officers, the researchers invited members to participate by email distributed on the Division 46 listserv. The email invitation contained an explanation and a link to a secure online survey.

Questionnaire

The full questionnaire had 11 primary and 7 optional questions, comprised of scaled, open-ended, and demographic questions. This paper focuses on the open-ended question that directly addresses the definition of media psychology: “What comes to mind when you think of media psychology?” and the related demographics of the participants.

Analysis

The open-ended questions were analyzed using content analysis facilitated by SPSS Text Analysis for survey, based on a grounded theory approach, consistent with Strauss and Corbin (1997). A preliminary sample was taken from a pilot study and analyzed for general themes and categories to use as the starting point in category development for the full data set, as suggested by Neuendorf (2002). The responses were then codes, reviewed and recoded by hand to capture the subtlety of concepts and contextual meanings. The data frequencies produced categories that were merged into broader content themes. After completing the qualitative coding, the data was converted into binary coding as follows: 1 = mentioned; 0 = not mentioned. Responses could be coded into multiple categories. The quantitative data was analyzed using SPSS statistical software.

Results:

Qualitative Analysis

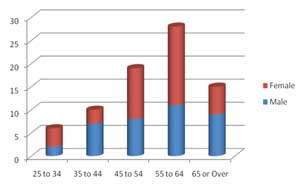

There were 92 records collected; 6 records had no response to this question, thus N = 86. Of the respondents, there were 47 females, 40 males. 54% of the respondents were between the ages of 45 and 64, as shown in Figure 1. Categories were created and emerging themes identified. The following list is the top six themes in order of frequency:

1. The human factor

2. Psychological content delivery

3. Media effects

4. Research

5. Integrated definition: interaction between media and psychology

6. Media types

Figure 1. Demographics

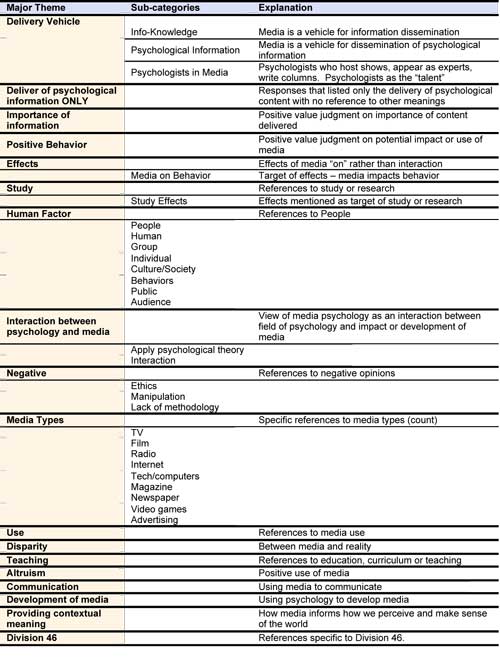

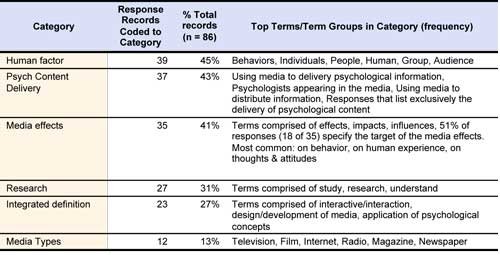

Table 1 shows the complete category coding list from which the themes were derived. Table 2 shows the major category themes and frequencies.

Table 1: Qualitative Coding Categories

Table 2: Major Category Themes and Frequencies

The perceptions of media psychology from the data can be summarized as:

- Functional

- How media is used to delivery psychological information to people

- How people use media.

- Theoretical

- How media effects people and their behavior

- How psychology contributes to media development

The Human Factor Theme

45% of the respondents identified the human component in their conception of media psychology. These responses—including culture, society, people, self, human, behavior, experience, audiences, groups and individuals—appeared across all categories.

The Passive vs. Interactive Theme

Responses indicated both narrow and broad perceptions of media psychology with different emphases on the functions of media. Using the passive and interactive conceptualization traditional versus new media by Negroponte (1995), the responses were coded into similar constructs. Passive was defined as media serving as a distribution device or as a separate entity separated from the individual or group; interactive is where psychological theory frames the intersection of media and the individual or group.

43% viewed media passively. This included responses such as ‘psychologists who appear in the media as experts’ as well as the delivery of psychological information and material using the media. In this conceptualization, psychology and media are separate domains, with media serving a distribution function for psychology. Examples:

“Psychologists hosting a show. Experts on TV shows as guests. Newspaper columns.”

“The ways in which psychologist can be present in various media.”

“Media that present psych messages or psychologists in media.”

“Talking to the media about psychological issues relevant to a particular audience. Using the media to disseminate important psychological topics and ideas.”

27% reported a view of media and psychology as interactive domains with the application of psychology as framework for evaluating and developing media, and understanding impact and use. Examples:

“Theory, research and practice of psychology related to all the media previously noted. Psychologists in the media, psychologists influencing media style and substance, psychologists studying media impacts on audiences and behavior…”

“The application of psychological concepts in the furthering of the betterment of our media as well as understanding the impact of media on the individual as well as our global society.”

“The psychology of media, the psychological impact of media as well as how media is used to manipulate the psyche.”

In 15% of the cases, both approaches were mentioned within the same response. Example:

“‘Expert’ opinion on psychological issues, development and analysis of new media.”

In some cases, respondents referred to their perceptions of a dichotomy within the field. Example.

“Two disparate groups: Psychologists who study the effects of media and psychologists who want to use the media to get messages out.”

Media Impact, Effects and Research Theme

Media Effects appeared in 41% of the responses with over 70% of these referring to the study or research aspect. Respondents more often described media effect as a passive event (e.g. “impact of media on the public”) rather than interactive. Media effects also included references to influence and control, such as “how the various forms of media…influence society.”

“Studying effects of media on people’s behavior.”

“The study of how media impacts upon human behavior.”

“The impact of media on the public .”

“Research on the effects of media…”

“Understanding how media affects people…”

Media Types Theme

Respondents employed the word “media” to describe media psychology in 65% of the responses. It appears much more frequently than specific media types. Of the media types identified, ‘traditional media’—television, film, movies, radio, magazines, journals, and newspapers—were 3 times more prevalent than those of ‘new media’—internet, computers, video games.

The lack of specific articulation for the term ‘media’ raises two questions. Does this imply uncertainty on the part of the respondent as to the definition of media psychology or is the word ‘media’ shorthand for the range of technology and applications it encompasses? The lack of specificity confounds our ability to judge the breadth of a respondents’ perception. Media could equate with ‘television’ or a broad spectrum of different media.

Positive and Negative Remarks

14% of respondents referred to the contributions media psychology can make to society.

“How to help people learn effectively through media.”

“Share useful information with the public/informing the public.”

“Getting accurate information out to the public…educating the public.”

Negative comments reflected the primarily ethical issues, such as ethics in appearing in the media as an expert, a lack of rigor in the field, the self-promotional aspect of appearing in the media, and concerns about manipulating public thought through propaganda or spin.

“Manipulation. Business and politicians creating advertising and propaganda to put ‘spin’ in what they are saying so that they can manipulate our thinking… “

“…Not how to carry on an interview or how to promote your self help book.”

Influence of Demographic Variables

Using a Chi Square Tests, we analyzed the relationships between demographics Age, Gender, and Occupation each of the major themes that emerged in defining media psychology.

Of the independent variables, only age had a significant relationship with any of the themes that emerged. These themes, ‘Using Media to Distribute Psychological Information Only’ and ‘An Integration of Psychology and Media’, represent a dichotomy in the points of view. The relationship between Age and these contrasting perceptions of media psychology were both significant at p<. 05 level, indicating that the likelihood of viewing media psychology as ‘an integration of media and psychology’ decreases with age (-.0481); while the likelihood of having a perception of media psychology as ‘using media to deliver only psychological content, either as information, expert guest, or host,’ increases with age (+.0641). While the effect is not large, it may represent a shift in the outlook of newcomers to both the Division membership and profession.

Division 46 Website

As a final piece of this project, researchers examined the Division 46 website to see if the content is representative of the perceptions of the polled members. This is important because the Division 46 website home page stands as a primary source for the definition of media psychology on the web. A current Google search shows the APA Division 46 in the top three returned links for a search on ‘media psychology.’ Thus the Division 46 website carries the potential burden and privilege of providing an introduction to media psychology to a wide audience.

Content analysis shows that the website material subtly emphasizes the distribution aspect of media for psychology, relative to other applications. This begins in the first paragraph though the use of the word “roles”—a performance-related word choice—followed by a media list of performance driven mass media. The specific listing of traditional media (television, video, radio) emphasizes these types of media at the expense of the generically referenced (‘newer technologies’), thus making it more difficult to visualize newer media.

Division 46 – Media Psychology focuses on the roles psychologists play in various aspects of the media, including, but not limited to, radio, television, film, video, newsprint, magazines, and newer technologies.

The emphasis on media as a distribution path implies separate domains for media and psychology rather than an integration where media development and analysis is informed by psychology. This separation is reiterated in the following sentence:

“To facilitate interaction between psychology and media representatives”

In this example, the grammatical construction suggests that the interaction is between psychology and media representatives rather than media, implying a separation between media professionals and psychology professionals.

The site content is consistent with a majority of Division 46 respondents who reported a perception of media psychology as either using media to deliver psychological content or as studying the impact of media. It does not, however, do justice to the point of view the 31% of respondents, more frequently younger members, who conceptualize media psychology as a broad and integrated field of study.

Limitation of the Study

While every effort to engage all members of Division 46, our results do not include all perceptions and attitudes within the Division. Our sample represents slightly less than 10% of the total membership. Even were we to have had a much higher level of participation, there are many professionals working in what would qualify as media psychology who are not members of Division 46 and whose opinions were not tapped.

The term “media” was used repeatedly to define media psychology and media use and impact. The lack of specific articulation for the term ‘media’ raises two questions: is this uncertainty as to the definition or is it shorthand for the range of technology and applications it encompasses? The lack of specificity limits our ability to judge the range of a respondents’ perception.

There were multiple references to the impact and effect of media raises questions as to the meaning of these terms. ‘Media Effects’ could be referring to one of the original (Chafetz et al., 1998)media’s influence (Stevenson, 2002), a more recent permutation where individual differences and preferences came into play (Giles, 2003), or a more general sense that human experience is inseparably from media and, therefore, impacted by it. This uncertainty as to meaning also leaves us with little ability to understand the respondents’ perception of individual agency in the process of media interaction.

Conclusion

We view this study as an exploratory foray to start a dialogue in an emerging and important field. We hope to this study provides a framework and baseline for future research and educational efforts.

We think there is potential for understanding the perception of media effects and impact. Although a frequent response, the data left many questions unanswered about the respondents’ perception of agency relative to media, i.e. whether individuals and society are perceived as victims of media’s influence or interactive participants. Both areas will be important for further study as they hold implications for the effectiveness of media applications in areas such as education, healthcare and public policy.

A few remarks also raised questions about the ethical issues surrounding media technologies. This suggests a need for clarified and more functional ethical guidelines in the emerging field of media psychology and this is an area where psychologists can make a significant contribution.

As practitioners and researchers in an emerging field, it is up to us to define the field and set the standards for media psychology. To this end, we recommend:

Addressing the disparity in how media psychology is perceived by making more people aware of the current, potential, and positive uses in the field through increased research, publishing and applications. We would encourage Division 46 to play an increasingly central role by expanding content on the Division 46 website. The content, functions as the main source of information about media psychology for the APA, was more consistent with the view of older members. The challenge for Division 46 is to promote a meaningful definition that supports all of it membership so that newer members feel represented and use their energies to support the Division. To do this means the Division must promote the idea of media psychology as an inclusive, pioneering, integrative and multi-disciplinary field rooted in the rich history of psychological theory and practice.

References

Amory, A., Naicker, K., Vincent, J., & Adams, C. (1999). The use of computer games as an educational tool: Identification of appropriate game types and game elements. British Journal of Educational Technology, 30(4), 311-321.

Chafetz, P. K., Holmes, H., Lande, K., Childress, E., & Glazer, H. R. (1998). Older adults and the news media: Utilization, opinions, and preferred reference terms [Electronic Version]. The Gerontologist, 38, 481. Retrieved September 29, 2007, from, http://proquest.umi.com/pqdweb?did=33346497&Fmt=7&clientId=46781&RQT=309&VName=PQD.

Cline, R. J. W., & Haynes, K. M. (2001). Consumer health information seeking on the Internet: The state of the art [Electronic Version]. Health Education Research, 16, 671-692. Retrieved September 2, 2006, from, http://her.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/16/6/671.

Coltrane, S., & Messineo, M. (2000). The perpetuation of subtle prejudice: Race and gender imagery in 1990s television advertising [Electronic Version]. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 42. Retrieved October 12, 2007, from JStor.

Derwin, E. B., de Merode, J., & Shayne, J. (2006). Analysis of the media psychology journal content. Unpublished Presentation. Fielding Graduate University.

Diesch, C. L. F., & Caldwell, J. (1993). Where are the experts? Psychologists in the media. Paper presented at the 101st annual convention of the American Psychological Association. from http://www.apa.org/divisions/div46/articles.html

Fischoff, S. (2005). Media psychology: A personal essay in definition and purview [Electronic Version]. Journal of Media Psychology, 10. Retrieved April 18, 2006, from, http://www.calstatela.edu/faculty/sfischo/MEDIADEF-1.html.

Giles, D. C. (2003). Media psychology. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Luskin, B. (2002). Casting the net over global learning. Irvine, CA: Griffin Publishing Group.

Luskin, B. J., & Friedland, L. (1998). Task force report: Media psychology and new technologies. Washington D.C.: Media Psychology Division 46 of the American Psychological Association. Retrieved June 2, 2006, from http://www.apa.org/divisions/div46/articles/luskin.pdf

Negroponte, N. (1995). Being digital. New York: Vintage Books.

Neuendorf, K. A. (2002). The content analysis guidebook. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Oliver, M. B., Shrum, L. J., & Vorderer, P. (2006). Moving on [Electronic Version]. Media Psychology, 8, 61-63. Retrieved August 30, 2006, from, http://www.leaonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1207/s1532785xmep0802_1.

Prabu David, G. M., Melissa A. Johnson and Felecia Ross. (2002). Body image, race, and fashion models: Social distance and social identification in third-person effects [Electronic Version]. Communication Research, 29, 270-294. Retrieved September 22, 2007, from LEAonline database.

Rideout, V. J. (2007). Parents, children & media: Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrieved October 5, 2007, from http://www.kff.org/entmedia/upload/7638.pdf

Rudestam, K. E. (2004). Distributed education and the role of online learning in training professional psychologists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 35(4), 427-432.

Rutledge, P. (2007). A definition of media psychology [Electronic Version]. Retrieved April, 12, 2008, from, http://www.mprcenter.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1&Itemid=64.

Spielberger, C. (2006). President’s column: Clarifying our goals and moving forward [Electronic Version]. The Amplifier. Retrieved August 20, 2006, from, http://www.apa.org/divisions/div46/AmpSum06_bw.pdf.

Stern, S., & Mastro, D. E. (2004). Gender portrayals across the life span: A content analytic look at broadcast commercials. Mass Communication and Society, 7(2), 215-236.

Stevenson, N. (2002). Understanding media cultures (2nd ed.). London: Sage Publications.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1997). Grounded theory in practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Note:

Additional researchers and contributors included:

Erik Gregory, Media Psychology Research Center

Jonathan Cabiria, Baker College

Jerri Lynn Hogg, Bay Path College

Lynn Temenski, Fielding Graduate University

Timothy Wells, Rochester Institute of Technology