Moral Choice in Video Games

Daniel M. Shafer, PhD

Baylor University

Abstract:

Abstract:

Recent research on the process of enjoyment of violent computer/video games suggests that Klimmt et al’s theoretical perspective of moral management, which incorporates Bandura’s concept of moral disengagement, may play a significant role. However, games involving moral choice have not yet been fully considered. In this study, 83 players were randomly assigned to one of three moral choice game scenarios. Results indicate a strong relationship between morally activated/disengaged reasoning and moral choice. However, those who made the good choice and those who made the evil choice enjoyed the game equally.

Daniel M. Shafer, Ph.D. is Assistant Professor of Film and Digital Media at Baylor University in Waco, Texas, USA. His research interests include media psychology, video game enjoyment, and morality in entertainment media, as well as effects of new communication technology. His articles have appeared in Mass Communication and Society and Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments. He received his doctorate from Florida State University.

Daniel M. Shafer, Ph.D. is Assistant Professor of Film and Digital Media at Baylor University in Waco, Texas, USA. His research interests include media psychology, video game enjoyment, and morality in entertainment media, as well as effects of new communication technology. His articles have appeared in Mass Communication and Society and Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments. He received his doctorate from Florida State University.

Video games with plotlines involving moral choices are increasing in number, according to voices in the gaming community (McCalmont, 2009; Floyd & Portnow, 2010). Games such as Mass Effect (Bioware, 2007) and Fallout 3 (Bethesda, 2008) require players to choose between actions that can impact their standing with non-player characters (NPCs) and affect the skills and abilities they can use (Schulzke, 2009). Recently, issues of morality in games have caught the attention of the public, the media, and a few scholars. Consider the controversy surrounding the 2009 release of Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 (Heining, 2009). In one mission, players carry out a terrorist attack on civilians in an airport, a disturbing moral scenario that some said went too far, despite the game’s warning and opt-out mechanisms (Heining, 2009).

However, what the discussion and controversy fail to address is the entertainment value of games with moral choices built in, and the implications of playing these types of games. Empirical, data-driven research on this issue are few, limited to two or three studies (e.g., Klimmt, Schmid, Nosper, Hartmann & Vorderer, 2006; Hartmann & Vorderer, 2010) However, relevant philosophical considerations have been offered that give insight into the nature of players as moral agents and how moral systems in games work (e.g., Schulzke, 2009; Sicart, 2009; Zagal, 2009). Klimmt et al. (2006; Klimmt, Schmid, Nosper, Hartmann, & Vorderer, 2008) argue from a theoretical framework they term ‘moral management’. Their perspective, which relies heavily on Bandura’s (1986; 1999) notion of moral disengagement, asserts that video game players use varying cognitive strategies to absolve themselves of guilt or justify certain morally questionable acts (such as killing) undertaken while playing games. Players do this, the authors argue, in order to perpetuate their enjoyment of said games (Klimmt et al., 2006; 2008). However, the moral management perspective does not consider games where a player is offered a choice between two or more courses of action. Games with such choices are becoming more popular, especially in the role-playing game genre (e.g., Mass Effect 3, Fallout: New Vegas, Skyrim, and Star Wars: The Old Republic). Therefore, this article addresses the following two questions. First, is activation or disengagement of one’s moral principles associated with the decision to make a good choice over an evil choice? And second, are there differences in enjoyment based on the moral choice one makes in a videogame? The possible implications of long-term play of moral choice games will also be discussed.

Morality and Video games

Moral considerations in video games have been under academic scrutiny for several years. Schulzke (2009) presented a philosophical discussion of how moral choice has recently become more popular and more expertly presented in video games such as the Fallout series (Schulzke, 2009). Fallout 3, for instance, allows for moral choices such as destroying a town to get an apartment and a sizable monetary reward; or saving the town in order to preserve innocent lives. The reward is then a shack in town and a lesser sum of cash. Other choices involve shaking down a drug addict for money or just killing her and robbing the corpse; or selling a number of rare soft drinks to a man in a town who hopes to trade them for sex, or just giving them to his target directly for less money. On a larger scale, many quests allow for a peaceful or violent resolution – however the peaceful solutions sometimes involve lying, computer hacking, theft, or breaking and entering (Bethesda, 2008). Schulzke (2009) posits that such games are engaging and realistic, and offer a deeper experience than games without a moral choice engine. He goes so far as to say that the moral dimension adds to enjoyment, but, due to the nature of his discourse, offers no empirical evidence to support this claim (Schulzke, 2009).

Sicart (2009) ponders the implications of games that incorporate moral components such as placing players in uncomfortable ethical dilemmas or use moral systems as in Deus Ex (Eidos, 2011). In Deus Ex: Human Revolution, there is no good or evil rating scale. In conversation, various options are offered such as “Confront”, “Defend”, “Absolve” that govern the tone of the avatar’s responses. In addition, there are often several options for completion of quests; a diplomatic or less violent option, or a cold-blooded killing option (Eidos, 2011). Sicart argues that when players enter a virtual world such as the one created in Deus Ex, they are still “morally aware and capable of reflecting upon the nature of… acts within the game world” (Sicart, 2009 p. 62). Sicart points out that playing a game does not change the nature of who we are as human beings, and that actions, even in a virtual world, still carry implications (Sicart, 2009). This point is important to the present discussion, because if players enter a game world having left all morality behind, then moral concerns make no difference and in-game actions are meaningless. But if players enter into a game as moral beings, as ethical agents (Sicart, 2009), then what they do in the game is meaningful.

Screenshot: Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 “No Russian Mission”

Zagal (2009) considers the ethical implications of playing games which present players with moral dilemmas. According to Zagal’s reasoning, games that have components with ethical implications built in encourage moral reflection. For instance, consider Ultima IV which forces players to favor certain virtues over others (such as valuing honesty over compassion or humility or honor; Origin, 1985), Zagal (2009) argues that Ultima IV “attempts to make the player feel personally invested or responsible for the decisions they make…” (p. 4). If players, in fact do feel responsible for what they do in games, what then are the psychological mechanisms by which those feelings are wrought? What happens in the mind when players either choose to or are required by the game system to violate their own “standards of morality?”

Klimmt and colleagues argued that players can and do disengage their usual sanctions against morally questionable behavior in order to enjoy acts of violence in video games (Klimmt et al., 2006; Klimmt, Schmid, Nosper, Hartmann, & Vorderer, 2008). The authors offer a theoretical perspective known as moral management; a process by which disengagement cues imbedded in the game narrative interact with players’ desires to win the game (Klimmt et al., 2006; 2008). The result is a cognitive abandonment of moral concerns, which allows players to enjoy games even when they are expected or required to perform morally reprehensible acts.

Hartmann and Vorderer (2010) found that moral disengagement cues in violent games both increased and decreased enjoyment. Acting as the “bad guy” in the game enhanced negative feelings, but did not impact enjoyment of the game. The authors argued that gamers may have felt effective, powerful, and excited, diminishing guilt and negative affect and allowing enjoyment to continue (Hartmann & Vorderer, 2010).

Furthermore, Hartmann, Toz, and Brandon (2010) reported players feeling guiltier in the unjustified violence gaming condition, or if they knew more about the enemy’s background. So far, research on morality and video games has concluded that moral judgments are an important part of game play, and that players take steps to absolve themselves of guilt for violent actions taken in virtual worlds.

Real-World Moral Choice

The moral choices we make in the real world depend, at least in part, on our personal moral code or sense (Hauser, 2006). The pertinent question in a study such as this, however, is how real-world moral judgment and choice translate to the fictional game world. There is evidence that gamers have real emotional responses to videogame characters, treating them as social beings (Scholl and Tremoulet, 2005). Because players of violent video games are required to kill other social beings, it is understandable that playing violent video games may cause very real emotional and moral problems for those gamers (Elton, 2000). However, gamers report greater enjoyment when playing violent games, and do not feel that committing game violence is wrong (Jansz, 2005). It stands to reason that gamers’ reactions to moral situations in video games would be tied to their own personal sense of morality, as well as other individual attitudes. An individual’s sense of morality can vary greatly (Bandura, 1986; Zillmann, 2000), but there are both normative and descriptive approaches to an individual’s moral standards.

Screenshot: Fallout 3 “Into the Pitt“

Descriptive morality refers to a specific group’s or society’s code of conduct, while normative morality refers to a code of conduct that would be intuitively understood by all rational individuals (Gert, 2002; Hauser, 2006). Those who hold to the normative morality perspective, that is, that a universal code of conduct exists that governs the actions of all rational individuals, agree that an average adult in any society has a basic sense of what this universal morality allows and prohibits (Gert, 2002). However, as Bandura (1986) points out, people vary greatly in their moral reasoning, and even the same individual varies in his or her reasoning from time A to time B (Bandura, 1986). As Zillmann (2000) points out, individuals vary greatly in their perspectives on basal morality. Children are taught a system of morality by their parents and other socializing agents. It is likely that the moral code communicated by parents and other authorities is descriptive in nature, growing from the philosophy of the specific group to which those authority figures belong (e.g., Christians, Muslims, or the Amish).

Since individuals have an intrinsic (normative) sense of morality in addition to learning a moral code from a group (descriptive), it is clear that human beings use a mixture of types of reasoning (Bandura, 1986) and emotional gut reactions (Hauser, 2006) in the effort to determine what is morally righteous in a given situation. An additional strategy that is used by people faced with moral choices is moral disengagement. Theory and empirical research demonstrate that moral disengagement is utilized in real, hypothetical, and virtual moral choices (e.g., Bandura, 1986; McAlister et al., 2006; Klimmt et al. 2006; 2008; Hartmann and Vorderer, 2010).

Social Cognitive Theory and Moral Disengagement

According to social cognitive theory, human beings vary in their tendency to morally disengage (Bandura, 1986).The stronger an individual’s self-sanctions against morally questionable behavior; the less likely that person would be to morally disengage. Instead, such an individual would tend to be morally activated>/em>(Bandura, 1999).

Moral activation. Bandura (1999) points out that, upon considering a past, present or future act, self-sanctions can either be activated or disengaged. Human beings do not use their self-regulatory ability unless it is activated (Bandura, 1999). As humans encounter situations of moral choice, then, self-regulation is essentially in a neutral position. Various factors, such as individual self-worth and tendency towards moral disengagement, as well as other individual difference factors, can impact whether self-sanctions against reprehensible conduct are activated or disengaged (Bandura, 1986; 1999). Given these facts, individuals may find their moral standards activated. On the other hand, some may find themselves using any of the eight following mechanisms in order to justify morally reprehensible conduct or alleviate guilt over such conduct (Bandura, 1999; 1986).

Moral disengagement mechanisms. Bandura (1999; 1986) describes eight mechanisms of moral disengagement. Moral justification is achieved when a behavior is reconfigured in the mind, which allows an individual to believe that the harmful behavior is serving morally acceptable purposes; a moral mandate (Bandura, 1999). The use of euphemistic language or labeling is done to avoid offending others with guilt-inducing terminology. In the context of moral disengagement, using euphemisms helps to make reprehensible action or behavior seem less despicable, allowing for more cruelty (Bandura, 1999). In advantageous comparison, the reprehensible behavior in question is compared to some more egregious act in order to make one’s own despicable action appear humane (Bandura, 1999). Displacement of responsibility places blame for the action and its consequences away from the agent and onto some authority (Bandura, 1999). Agency is passed from the individual on to the leaders, and guilt is reduced. Diffusion of responsibility shifts blame, spreading it across several group members who share responsibility (Bandura, 1999). Next, guilt can be absolved through distortion or disregard of consequences. Distance aids in this disengagement strategy. For instance, leaders who order destructive tactics in war are far removed from the consequences of their orders, and weapons technology allows the killing of enemies from a distance (Bandura, 1999). Attribution of blame is the reasoning that the victims deserve whatever has been done to them. Also, it can be claimed that the victims provoked the aggressor, and are now simply getting what they deserve (Bandura, 2004). Dehumanization strips humanity from the victims of deplorable acts, or assigns bestial qualities to them. Individuals seen as less than human are easier to kill or harm (Bandura, 1999).

Klimmt et al.’s (2008) moral management perspective adds a ninth mechanism; the idea that the player can be absolved of negative feelings by reminding themselves that what they are doing in the game is virtual: no actual killing takes place, and no real property is destroyed – “It’s just a game”.

The Current Research

In the present study, it is expected that players confronted with moral choices in video games will make those choices based either on their personal moral standards which have been activated, or based on moral disengagement mechanisms. It is expected that responses to free-response questions probing the reasons behind or justifications for the choice made in-game will be associated with morally activated or morally disengaged reasoning, as has been found in previous research (i.e., Klimmt et al., 2006).

Recent research has indicated that players of violent video games who fight for a just purpose feel less guilty and report less negative affect than those who are placed on the bad side or fight for an unjust purpose (Hartmann & Vorderer, 2010) However, Hartmann and Vorderer (2010) found no differences in enjoyment between conditions. Because of inconclusive evidence, no prediction can be made as to whether the good or evil choice will be more enjoyable to players. Therefore, the following research question is posed:

RQ1:Who will report the most enjoyment of the games involving moral choice – those who make a morally righteous choice, or those who make a morally reprehensible choice?

Research has shown that moral disengagement strategies are used by videogame players in order to make virtual killing more palatable (Klimmt et al., 2006). Moreover, some moral disengagement cues in the games seem to help players disengage from violent acts against videogame characters (Hartmann & Vorderer, 2010). Past research has shown that higher predisposition to moral disengagement results in a more favorable response to military action (McAlister, 2000; McAlister, Bandura & Owen, 2006) and state sanctioned executions (Osofsky, Bandura, & Zimbardo, 2005). Although this evidence points to the idea that moral disengagement takes place in serious and extreme situations, Bandura (2004) argues that individuals use moral disengagement mechanisms in everyday situations. Even decent people often have no qualms about making self-promoting choices that have injurious effects on other people (Bandura, 2004).

Taking these findings into account, the following prediction is made:

H1: moral activation will be significantly associated with making the good choice; and moral disengagement will be significantly associated with making the evil choice.

This study also proposes to investigate the possible mediating effect of moral choice between moral activation/disengagement and enjoyment. It would seem that morally disengaging would lead to more morally reprehensible choices in the game, as predicted in H1, but are these morally disengaged choices more or less enjoyable than the choices made when players are morally engaged? Therefore, the second research question is posed:

RQ2: Is there a mediating effect of moral choice on the relationship between moral disengagement/activation and enjoyment?

Methods

Participants. Data were collected from 110 students recruited from various courses at a mid-sized research university in the southern-central U.S. They were offered course or extra credit for their participation. Demographic data indicated the sample was 55% female and 84% White (non-Hispanic). Participants ranged in age from 18-27 with an average age of 20.4 years.

Stimulus Material. Players were randomly assigned to play one of three game scenarios which presented players with good or evil moral choices. Rather than engaging in the complex and no doubt perilous discussion of what is meant by the term “evil”, it seems prudent to offer operational definitions particular to this study. For the purposes of the present study, a “good” moral choice is one which allows the lives of innocents to be spared. This does not always mean that the good choice is nonviolent. In two of the following scenarios, a good choice may be made while still engaging in violence. An “evil” choice, then, is a choice that threatens or destroys the lives of innocents. Each moral choice scenario has an option which involves the killing or sacrificing of innocent lives to further a goal in the game. An evil choice, then, is more sinister than a violent choice, because it is done with a seemingly casual disregard of the sanctity of life. This disregard for the sanctity of life is regarded by many philosophers and most of the major religions of the world as fundamentally evil (e.g., Quran, n.d.; Schweitzer, 1946; The Bible, n.d.).

The following scenarios are part of three single-player video games played on the PC platform. In the “No Russian” mission from Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 (Infinity Ward, 2009), the player attacks civilians in an airport with a terrorist group. The choices of action are 1) shoot everyone except teammates (evil choice), 2) shoot only the guards who are trying to kill them (good choice), or 3) don’t shoot (good choice), which results in eventual death.

In “The Power of the Atom” from Fallout 3 (Bethesda, 2008), the player arrives at a town called Megaton; distinctive because of the live atom bomb at its centre. The sheriff of the town asks for help disarming the bomb and offers a small cash reward. Players then walk to the local saloon, where they meet Mr. Burke, who offers a larger sum to detonate the bomb. The player must then choose to 1) defuse the bomb (good choice), or 2) rig it to explode (evil choice).

In “Free Labor” from the Fallout 3 downloadable content (DLC) Into the Pitt (Bethesda, 2008), the player travels to Pittsburgh (“the Pitt”) where diseased and suffering slaves are under oppression by a man named Ashur. There is a cure for the disease, which resides in the blood of Ashur’s baby daughter. To retrieve the cure, the baby must be kidnapped and taken to Wernher, the rebellion leader, who will attempt to extract it. However, Ashur says the cure can be synthesized safely from the baby’s blood. The player then has the choice to either 1) Kidnap the baby (evil choice) or 2) Spare the baby (good choice).

Screenshot: Fallout 3

Experimental Procedure. Participants were seated in front of a multimedia station with a 32” television displaying the online questionnaire. Participants completed the pre-game demographics portion; then played the randomly assigned game for about 15 minutes. They then completed the enjoyment and choice measures, and the free response question about the reasons for their actions. Each session lasted 30-40 minutes.

Measures. Good or evil choice was determined by asking players what choice they made in the game. “No Russian” players were asked: “If you played Modern Warfare 2, did you shoot the civilians or not shoot the civilians?” and: “If you played Modern Warfare 2, did you try to shoot the terrorists you were supposed to be working with?” A single item assessed the choice in “Power of the Atom”: “Did you defuse the bomb, or blow up Megaton?” while “Free Labor” players were given the answer choices: “I kidnapped the baby” or “I did not kidnap the baby”.

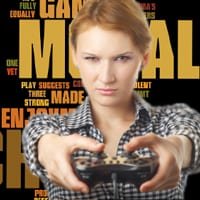

In order to assess whether a player was morally activated or morally disengaged, participants were asked to write two or three sentences about the choices they made in the game. Each response was categorized according to how it aligned with one of Bandura’s (1986) eight disengagement mechanisms or the ninth “it’s just a game” mechanism from Klimmt et al. (2008). Responses fell into six categories. Category One comprised morally activated players; they expressed that what they chose was the morally righteous thing to do. Category Two included players using displacement of responsibility; the idea of following directions or orders, supporting the group, and/or fulfill the mission. Category Three included players using diffusion of responsibility; expressing the idea of following and imitating the NPCs. Category Four included players who used the “it’s just a game” mechanism. Category Five indicated use of attribution of blame, with players stating that they needed to shoot at characters that were shooting at them in order to stay alive. Category Six included statements that indicated technical problems with the game; or that a player was apathetic about the research process. These cases were dropped from subsequent analysis (n = 27) leaving 83 cases for final analysis. Some of Bandura’s mechanisms (i.e., advantageous comparison, dehumanization, moral justification, and disregarding the consequences) had no corresponding statements. Therefore, Category One represented statements that indicated moral activation, while the remaining categories represented statements that indicated various mechanisms of moral disengagement.

The categories were then recoded to produce two groups. Group 1 included morally activated players. Group 2 included players who reported using moral disengagement. Categories and example statements are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Justification Response Categories for In-Game Choices

Enjoyment was measured using a 13-item measure adapted from previous studies (Raney, 2005; 2002). Two sample items are: “The game was exciting” and “I enjoyed the game.” Answers fall on a continuum from “not at all” (0) to “extremely” (10). Reliability was high, Cronbach’s α = .91.

Results

RQ1 asked whether there would be differences in enjoyment based on the choice made. A one-way ANOVA procedure indicated that there was no significant difference in enjoyment between those who made the good choice (M = 5.35, SD = 1.95) and those who made the evil choice (M = 5.62, SD = 1.93), F1, 81 = .41, p = .52.

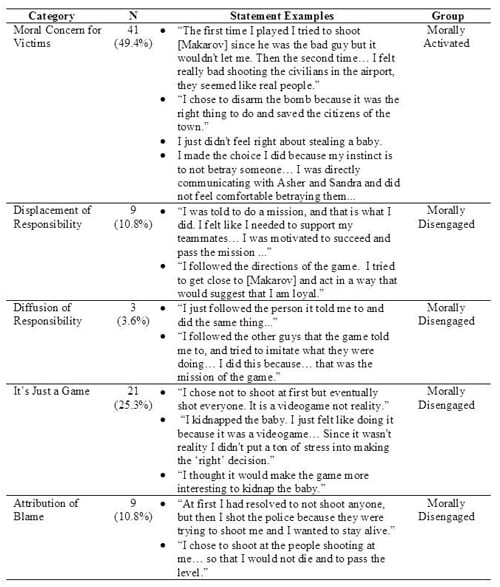

H1 predicted that players reporting being morally disengaged would tend to make the evil choice, while players reporting moral activation would tend to make the good choice. Results of a correlation procedure indicated that a strong, significant relationship exists between moral activation/disengagement and the choice made in the game, Pearson’s r = .480, p < .01. A crosstabs procedure with a Chi-square test indicated significant differences between the choices morally activated players made as compared to the choices of morally disengaged players, χ2 = 19.12, p < .001. The results showed that 82.9% (n = 34) of morally activated players made the good choice, while 17.1% (n = 7) made the evil choice. Conversely, 64.3% (n = 27) of morally disengaged players made the evil choice, while 35.7% (n = 15) made the good choice (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: N of Player Choices Made Based on Moral Activation or Disengagement

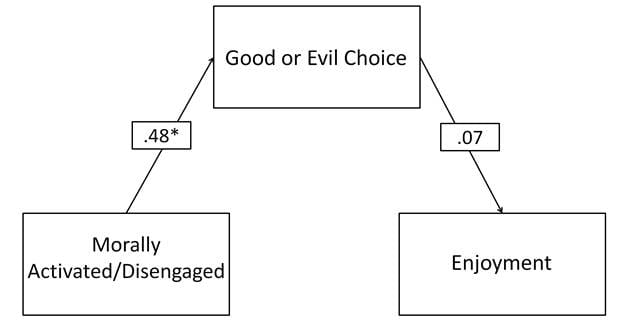

RQ2 inquired as to the possible mediating effect of moral choice on the relationship between moral activation/disengagement and enjoyment. In order to investigate this question, a path model was constructed. No variance in enjoyment was found based on choice or moral activation/disengagement (see Figure 2). Goodness-of-fit statistics indicated a good-fitting model, χ2N=83= 0.06, p = .81, df = 1, RMSEA = 0.00, AGFI = 1.00; NNFI = 1.17, CFI = 1.00; ECVI = .14.

Figure 2: Mediating Role of Choice between Moral Activation/Disengagement and Enjoyment

(* p < .01)

Discussion

Results of RQ1 show that players who made the evil choice did not enjoy the game significantly more or less than those who made the good choice. These findings are consistent with those of Hartmann and Vorderer (2010), who in several instances did not find variance in enjoyment despite differences in experimental condition (e.g., justified and unjustified motivations for violence). However, results of H1 suggest that moral activation/disengagement has a clear relationship with moral choices in video games. This finding can be explained by the fact that players bear the responsibility for the choices they make in the game. Those who make choices consistent with their own moral codes are likely to be satisfied with those choices. On the other hand, those who make morally disengaged choices have justified the choice to themselves. The most prevalent moral disengagement mechanism was the “it’s just a game” defense, with players reasoning that since the scenario was not real, their actions bore little consequence.

Players who used moral disengagement were significantly more likely to choose the evil options; while players who report being morally activated were significantly more likely to choose the good options. These results align somewhat with findings by Klimmt et al. (2006) who found that players of violent video games do use moral disengagement as they play. However, the Klimmt et al. (2006) evidence suggests that players use moral management in order to enjoy the game. The present evidence would suggest that using moral disengagement in moral choice games does not impact enjoyment, but rather impacts the route to enjoyment. Results of RQ2 support this conclusion in that there is no mediating effect of choice on the path from moral activation/disengagement to enjoyment.

It is important to point out that these results do not point to a causal path from moral disengagement to evil choices in video games. It is unclear when moral disengagement or engagement occurs in the process of playing and making moral choices. Morals may be disengaged before game play begins, just before each choice is made, after the choice, or all three.

This study adds to the nascent body of literature that focuses on moral disengagement in video games. The findings reported herein reinforce the findings of Klimmt et al. (2006) and Hartmann and Vorderer (2010), showing that moral disengagement plays a role in determining feelings experienced while playing video games. However, this study is also clear in its finding that many players, when faced with a moral choice, activated their moral sanctions against reprehensible behavior rather than disengaging them. So then, moral disengagement does play an important role in the cognitive and affective experience of violent video games. However, moral disengagement is not a necessary condition for enjoyment of moral choice games. Just as much enjoyment can be experienced by fulfilling the dictates of one’s personal moral code and following a morally activated path of action.

Limitations

This research is limited by the small number of games used. The games were broken into short, playable episodes as effectively as possible, but the few available resulted in a short list for inclusion in the present study. As such, the results reported herein may not be generalizable to all moral choice games.

Additionally, in this study it is impossible to determine when a player activated or disengaged moral standards. Players were asked to comment on their rationalization for the choice they made some time after they had been through the scenario, and may not have rationalized their choice before being asked.

Future Research

The findings herein have implications for real-world thought processes and behavior. In the short-term, effects are likely to be minimal, but concern might lie in the possible long-term effects of moral choice games, especially for those who tend toward moral disengagement. It is possible, for some players, that long-term exposure to moral choice games and frequent use of moral disengagement during these games could result in the construction of scripts for thought and behavior (Huesmann, 1986; Huesmann & Taylor, 2006) that are increasingly inclusive of moral disengagement. Moral disengagement could become habitual, translating into less moral activation in real-life decision making, leading to negative behavior. This effect could be attenuated by the conditioning effects of video games that incorporate powerful emotion-inducing elements (Huesmann & Taylor, 2006). For these reasons, more research on the possible impact of and the psychological processes behind moral choice in violent video games is warranted. Variables such as Presence and Flow surely play a role in moral decision making in games. Such an investigation falls outside the scope of the present study, but more research is needed. Future research should also engage players over several months, tracking their game play decisions and measuring individual differences to detect changes. Only then can scholars suggest what the long-term effects of playing such games may have on personal attitudes, morality, and behavior.

References

Bandura, A. (2004) The role of selective moral disengagement in terrorism and counter terrorism. In F. M. Moghaddam & A. J. Marsella (Eds.), Understanding terrorism: Psychosocial roots, consequences, and interventions. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association, p. 121–150.

Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3, 193-209.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought & action: A social cognitive theory. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bethesda. (2008). Fallout 3. [PC] USA: Bethesda Softworks.

BioWare (2007). Mass Effect.[PC] USA: Electronic Arts.

Eidos. (2011). Deus Ex: Human Revolution. [PC] USA: Square Enix.

Floyd, D., & Portnow, J. (2010) Video Games and Moral Choices [Video]. retrieved 19 September 2010 from: www.youtube.com/watch?v=6_KU3lUx3u0

Hartmann, T., Toz, E. & Brandon, M. (2010) Just a game? Unjustified virtual violence produces guilt in empathetic players. Media Psychology, 13 (4), p.339-363.

Hartmann, T., & Vorderer, P. (2010) It’s okay to shoot a character: Moral disengagement in violent video games. Journal of Communication, 60(1), p.94-119.

Hauser, M. D. (2006). Moral Minds. New York: HarperCollins.

McCalmont, J. (2009). The mechanics of morality: Why moral choices in video games are no longer fun” Retrieved 9/20/2010 from futurismic.com/2009/11/11/the-mechanics-of-morality-why-moral-choices-in-video-games-are-no-longer-fun/.

Heining, A. (2009). Modern Warfare 2 airport terror attack stirs controversy. The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 10/29/2011 from www.csmonitor.com/Innovation/Horizons/2009/1029/modern-warfare-2-airport-terror-attack-stirs-controversy.

Huesmann, L. R. & Taylor, L. D. (2006) The role of media violence in violent behavior. Annual Review of Public Health, 27, 393-415. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth. 26.021304.144640.

Huesmann, L.R. (1986). Psychological processes promoting the relation between exposure to media violence and aggressive behavior by the viewer. Journal of Social Issues, 42, 125-139.

Infinity Ward. (2009). Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2.[PC] USA: Activision.

Klimmt, C., Schmid, H., Nosper, A., Hartmann, T., & Vorderer, P. (2008) Moral management: Dealing with moral concerns to maintain enjoyment of violent video games. In A. Jahn-Sudmann, & R. Stockmann (Eds.), Computer Games as a Sociocultural Phenomenon. Hampshire, U.K.: Palgrave. p.108-118.

Klimmt, C., Schmid, H., Nosper, A., Hartmann, T., & Vorderer, P. (2006) How players manage moral concerns to make video game violence enjoyable. Communications—The European Journal of Communication Research, 31(3), p.309–328.

McAlister, A. L. (2000) Moral disengagement and opinions on war with Iraq. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 12(2), p.191-198.

McAlister, A. L., Bandura, A., & Owen, S. V. (2006) Mechanisms of moral disengagement in support of military force: The impact of Sept. 11. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 25(2), p.141-165.

Origin. (1985). Ultima IV [Atari] USA: Origin Systems.

Osofsky, M. J., Bandura, A., & Zimbardo, P. G. (2005) The role of moral disengagement in the execution process. Law and Human Behavior, 29(4), p.371-393.

Quran. (n.d.). Al-Mā’idah 5:32. Sahih International translation. Retrieved 30 May 2012 from http://quran.com/5

Raney, A. A. (2005) Punishing media criminals and moral judgment: The impact on enjoyment. Media Psychology, 7, p.145-163.

Raney, A. A. (2002) Moral judgment as a predictor of enjoyment of crime drama. Media Psychology, 4, p.307-324.

Schulzke, M. (2009). Moral decision making in Fallout. Game Studies, 9 (2). Retrieved 10 September 2011 from gamestudies.org/0902/articles/schulzke.

Schweitzer, A. (1946). Civilization and Ethics. London: Adam and Charles Black. Retrieved 30 May 2012 from http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=98827471

Sicart, M. (2009). The Ethics of Computer Games. Boston: MIT Press. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.baylor.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=259281&site=ehost-live&scope=site

The Bible. (n.d.). Exodus 5:32. King James version. Retrieved 30 May 2012 from http://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Exodus%2020:13&version=KJV

Zagal, J. P. (2009). Ethically notable video games: Moral dilemmas and gameplay. In Breaking New Ground: Innovation in Games, Play, Practice, and Theory, Proceedings of DiGRA 2009, available at http://www.digra.org/dl/db/09287.13336.pdf.

—

Screenshot sources:

Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 from GameDynamo.com

Fallout from g4tv.com