Descriptive captions and ideological beliefs as predictors of emotional response towards people in ambiguous photos

Anita A. Azeem, PhD*

John A. Hunter, DPhil

Ted Ruffman, PhD

Department of Psychology, University of Otago, New Zealand

Abstract

We conducted a randomized controlled experiment to investigate the role of descriptive captions (positive and negative valence) and ideological beliefs (Right Wing Authoritarianism – RWA and Social Dominance Orientation- SDO) on viewers’ emotional response towards ‘people of color’ in ambiguous photographs. We manipulated the caption conditions to suggest that the person’s actions were either ‘positive’ or ‘negative’ while keeping the visual stimuli consistent. Participants included 211 American and 201 Pakistani undergraduates who were randomly assigned to one of the four experimental conditions: (1) a positive caption, (2) a negative caption, (3) no caption, or (4) both positive and negative captions. For each experimental condition, the same images were presented and only the caption condition varied. Outcomes were recorded as emotional ratings towards the person in the photograph. We found a significant effect of caption manipulation even after a one-off exposure. Post hoc comparisons indicated that caption manipulation was caused primarily by the positive and negative caption groups. Positively worded captions predicted more favorable ratings whereas negatively worded ones accounted for less favorable ratings towards the pictured individual. We also found that the No Caption and Both Captions groups resulted in similar ratings.

Keywords: Positive captions, Negative captions, Picture captions, SDO, RWA

* Corresponding author: E-mail: anita.azeem@otago.ac.nz

Dr. Anita A. Azeem, MS/Mphil Clinical Psychology, PhD Psychology was born and raised as a religious minority in Pakistan. She was highly intrigued by the understanding of social identity and group processes and therefore studied these related phenomena for her PhD. She is also interested in childhood sociodevelopmetal issues. Anita.azeem@otago.ac.nz

Dr. Anita A. Azeem, MS/Mphil Clinical Psychology, PhD Psychology was born and raised as a religious minority in Pakistan. She was highly intrigued by the understanding of social identity and group processes and therefore studied these related phenomena for her PhD. She is also interested in childhood sociodevelopmetal issues. Anita.azeem@otago.ac.nz

Dr. John A. (Jackie) Hunter, BSc DPhil(Ulster) is an Associate Professor and has taught social psychology at the University of Otago since 1994. He continues to research issues relevant to social psychology. He has authored over 40 papers and supervised over 40 PhD, masters, and honors students. jackie.hunter@otago.ac.nz

Prof. Ted Ruffman, BA(York Can) MEd PhD(Tor) examines social understanding in infants, children, and in young and older adults. He has authored over 60 articles on these topics. He has 20 years of university lecturing experience, at both the graduate and undergraduate levels. ted.ruffman@otago.ac.nz

Introduction

When audience view a photograph of an unknown individual, what determines their emotional response towards the person? Are external cues like descriptive captions more significant or do pre-existing beliefs play a greater role? The present study aimed to answer these questions using participants from two diverse cultures: America and Pakistan.

Media Representations of Outgroup Members

Social psychologists have noted that often one’s identity is tied to how they associate with a social group. Social Identity Theory (Tajfel, 1982) explains that group membership offers individuals an awareness of their specific position in a social world and alongside provides an opportunity to understand and evaluate where others belong. Tajfel (1982) argued that the process of making the distinction between “us and them” changes the way people view each other, and because of this, intergroup interactions are frequently marked with mistrust and doubt.

Media representations of ethnic outgroups have been noted to sustain the ingroup vs. outgroup chasm. For instance, the media has recurrently labeled ethnic minority groups as ‘a burden on the nation’s economy’, ‘violators of tradition’, the ‘most important problem in the country’ as well as ‘a threat to us’ (Atwell Seate & Mastro, 2016; Dragojevic, et al., 2016). Prior research indicates that there are some specific trends attached to how the media represents different outgroups. For instance, African Americans have consistently been portrayed as ‘criminals’, ‘lazy’, ‘violent’, and ‘troublemakers’ (Staples, 2011) but Asian Americans are viewed as the perpetual foreigners who are ‘exotic’, ‘non-American’ and ‘unassimilable foreigners’ (Zhang, 2010). Post 9/11, terms like ‘Muslim extremists’, ‘Islamic terrorism’ and ‘Islamic fanaticism’ emerged as the most frequent descriptions of Muslims (Nurullah, 2010).

In summary, the media consistently makes specific distinctions between ingroup and outgroup members and highlighted ingroup supremacy.

News Framing and Its Implication

Framing Analysis (Goffman, 1974) proposes that journalists frame certain issues by highlighting specific aspects of the story while ignoring others. There are five main ways in which frames are created: metaphors, exemplars, catchphrases, depictions, and visual images (Gamson & Modigliani, 1989). As discussed above, specific outgroups are presented (framed) as the dangerous or unassimilable ‘other’. Such representations are not devoid of consequences as Entman (1991) noted, “By providing, repeating, and thereby reinforcing words and visual images that reference some ideas but not others, frames work to make some ideas more salient” (p. 7).

Recent studies have acknowledged that media frames can either a) increase prejudice towards minority groups by portraying them negatively or b) reduce prejudice by portraying them positively (see meta-analysis of 79 studies by Banas, et al., 2020). Unfortunately, the former is more prevalent, and higher media consumption has been linked to negative attitudes toward immigrants and homosexuals (Fuochi et al., 2019), African Americans (Dixon, 2008; Persson & Musher-Eizenman, 2005) and Muslims (Ahmed, 2017; Ogan, et al., 2013). Further, negatively framed descriptions have also been identified as predictors for higher anger and lower warmth toward minority groups (Shaver, at al., 2017)

Visual Framing of Outgroup Members

As mentioned, visual images may be used to create a framework for understanding people or phenomena. For instance, a frame could be introduced by the image that is chosen to be published; in how an image is edited (size, brightness) or the descriptive captions assigned to it (Sacchi, et al., 2007). For instance, Iyer, et al. (2014) found that exposure to a victim’s images aroused feelings of sympathy, whereas exposure to a terrorist’s images activated feelings of fear and anger amongst the participants. In this case, the frame was introduced in the selection of picture and eventually it impacted viewers’ support for policy changes. A few other studies have also found that visual representation influences a viewer’s cognition, emotions and behavioral responses. Parrott et al. (2019) identified two main themes in the visual representation of immigrants: human interest frame and political frame. The researchers reported that the former frame increased positive emotions and enhanced positive attitude amongst audience whereas the latter increased negative emotions and led to negative attitude. For instance, Bleiker, et al. (2013) noted a consistent visual presence of boats suggesting that a large numbers of people were entering the country and emphasizing how that was a problem for the country whereas there was a dearth of individual humanized stories (2% of the total representation) focusing on the stories of those individuals. Similarly, Farris and Silber Mohamed (2018) analyzed 338 images from three major US publications and found that illegality and criminality were the most frequent themes whereby immigrants were visually represented as illegally crossing border or in detention facilities.

Current research also suggests that photographs may help to establish a connection between the viewer and the depicted individual if the photograph captures human expressions, but also indicates that presenting an expressionless photograph may dehumanize the individual for the viewer (Fahmy 2004). In line with this idea, Batziou (2011) found by examining the visual representation of immigrants in newspapers from Spain and Greece, that immigrants were consistently dehumanized. Images of immigrants portrayed them as expressionless with no connection to the viewer and, in fact, most of the images were photographed from a safe distance implying that they could be dangerous and that it is important to keep a distance from them. Such representations are likely to elicit a cold response from viewers and possibly increase hatred and discrimination towards immigrants.

Similarly, a picture caption may be framed as positively or negatively. However, there is a general lack of research exploring the role of picture captions in news media and regarding outgroup perception. In particular, the interaction between picture and caption has been overlooked in prior studies and there is a focus on either one of them, but not both (Hamborg, et al. 2018). However, it is important to analyze the image and the text together as the addition or subtraction of text may change the picture’s meaning (Kerrick, 1959). Thus, the current study aims to answer: How would an image be perceived without any caption, with a positive caption only, a negative caption only, or with two alternate captions?

An issue regarding the biased choice of words accompanying images was recently raised against the US media after two similar images of people walking out of a grocery store with food were published following hurricane Katrina. Both images had similar content, but they were described very differently. An African American man was described as, “A young man walks through chest-deep flood water after looting a grocery store”, whereas a White couple were described as, “Two residents wade through chest‐deep water after finding bread and soda from a local grocery store” (Mikkleson, 2005). The difference in the frames of these captions is hard to miss. The big question it raises is, to what extent can these captions impact the audience’s perception? What would be the impact if these captions were swapped and the couple was described as ‘looting the store’, or if no captions were presented with the images? The current study aims to answer these questions and explore how viewers’ evaluations are impacted by caption manipulation.

Viewer’s Pre-Existing Beliefs

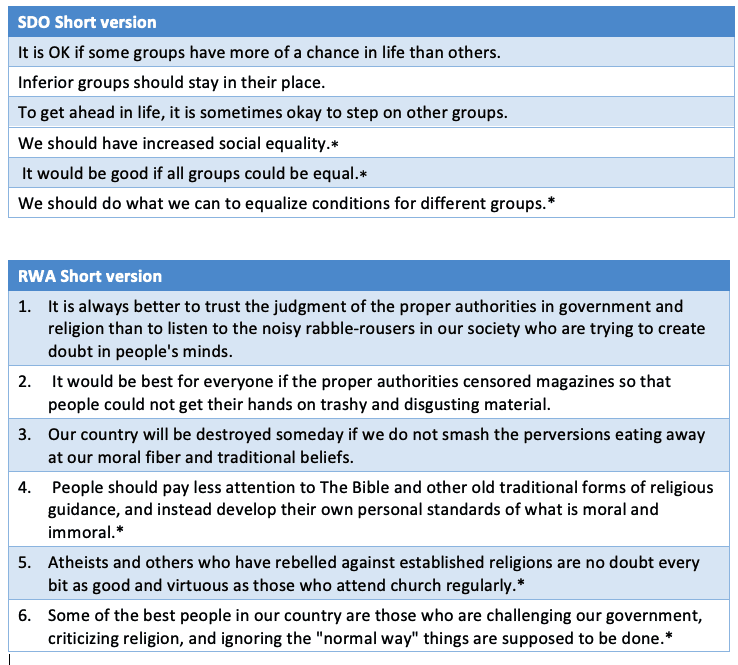

Indeed, media framing provides some insight into how the media creates a certain image for outgroup members. However, it is also important to note that the viewers will have pre-existing beliefs which may impact how they interpret incoming information. For instance, ideological beliefs such as Social Dominance Orientation (SDO) and Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA) are both strongly and independently correlated with prejudice (e.g., Altemeyer, 1998) and impact how incoming information is perceived (Crawford, et al., 2013; Esses & Hodson, 2006; Wright, etal.,2020).

Those high in SDO envision a ‘dog-eat-dog’ world and prefer the hierarchical organization of power, believing those at the top are worthier (Sidanius & Pratto, 2001). SDO is measured by the SDO scale (Ho et al., 2015), in which respondents endorse items such as, “Some groups of people must be kept in their place”, and, “We should not push for group equality”. RWA is characterized by a high degree of submissiveness to authorities perceived as established and legitimate, aggressiveness toward those who deviate from group norms, and adherence to normative social ideals (Altemeyer, 1998). It is assessed by items such as, “Obedience and respect for authority are the most important virtues children should learn”, and, “Women should have to promise to obey their husbands when they get married”. People who score high on SDO and RWA are more likely to endorse stereotypes when asked to report how they feel about people from another nationality (Strube & Rahimi, 2006).

Present Study

Thus, the purpose of the current study was to examine whether positive representation of outgroup members would impact how individuals feel towards them or would pre-existing beliefs be a more significant factor. The authors used three images of people of color with varying picture captions to examine participants’ responses from America and Pakistan

The hypotheses for this experiment were:

1) Participants who viewed positive captions would rate each pictured person more positively than those who viewed negative captions.

2) In the no caption and both captions conditions, ratings towards the pictured person will be higher than ratings in the negative caption group.

3) In America, participants higher in prejudiced attitudes (SDO and RWA) would rate the pictured individuals lower (more negative rating towards outgroup members), whereas in Pakistan, the trend would be reversed as presumably the participants would be able to relate more to the individuals in the pictures and would therefore perceive them as ingroup members

Method

Overview

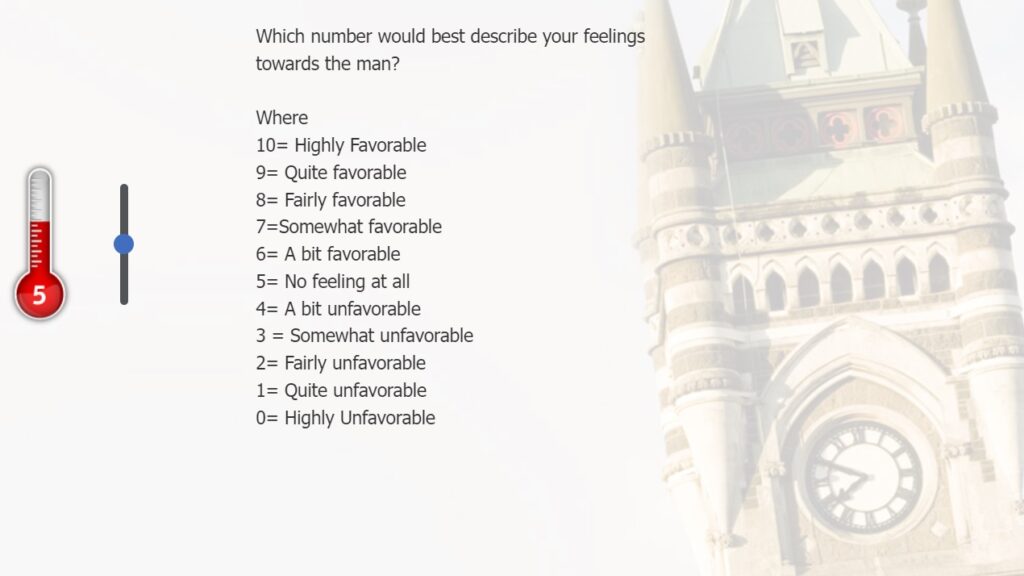

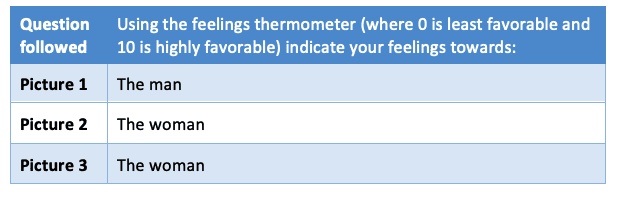

The participants were presented three experimental photographs which were inserted amongst three distractor photographs. Participants looked briefly at the photograph (and captions) and then answered some attention questions. This was followed by a question requesting participants to rate how they felt towards the person in the picture on a feelings thermometer from 0 (highly unfavorable) to 10 (highly favorable). These ratings were the dependent variable for this study. In addition, there were three independent variables, including Person Depicted (with three sets of people depicted in the pictures, but no clear prediction for different ratings for the three people), Experimental Group (positive caption, negative caption, both, neither), and Nationality (Pakistan or USA). SDO and RWA were subsequently examined as correlates of ratings.

Participants

American (n = 217) and Pakistani (n = 212) university students completed an online survey on Qualtrics. Of these, 213 American (M = 23.93 years, 112 females) and 201 Pakistani (M = 21.64 years, 117 females) participants had a near-perfect score on the attention questions (at least 5 out of 6 correct) and were retained for analysis. In the USA there were 64 participants who described themselves as religious (with 55 identifying as Christian) whereas in Pakistan there were 155 (with 146 identifying as Muslim).

Procedure

Participants were emailed a link to complete an online survey on Qualtrics. The research was introduced as measuring social attitudes. Participants from America were paid online via Prolific and participants from Pakistan received a burger discount voucher upon completion of the task. After providing informed consent and basic demographic information, participants completed the 6-item versions of the SDO and RWA scales (see Appendix A). The participants were then presented with three ambiguous photographs one-by-one (see Appendix B) and were asked to rate the person they had viewed (Appendix C).

Stimuli

The three experimental pictures included a Middle Eastern man pointing his finger at a woman wearing an abaya (a loose over-garment worn by Muslim women) in Figure 1. The second photograph showed a woman holding a small weeping child (Figure 2) and finally the third image showed a woman playing hockey ( Figure 3).

Figure 1: Image 1 titled ‘Man + Woman’.

Figure 2: Image 2 titled ‘Woman+ Child’.

Picture Courtesy: Raj Jalal

Figure 3: Image 3 titled ‘Sportswoman’

These pictures were chosen specifically so that they demonstrated people of color in different activities. We generated alternate captions for each of the pictures (one positive and one negative). Appendix B describes how these captions were presented to participants in the four experimental groups.

These pictures were pilot tested on a sample of undergraduate university students (N=30) to ensure that they were perceived as neutral pictures. Participants were asked to rate each picture from 0-10, where 0 was the least favorable and 10 was the most favorable. The results of the pilot study indicated that all the pictures were rated as somewhat neutral: Man + Woman, M=5.41, SD=2.87; Woman + Child, M=5.10, SD=3.18; Sportswoman, M=6.21; SD=2.77. Further, to ensure that positive and negative captions were perceived the way they were intended, the pilot study participants were asked to rate how positive (10) or negative (0) they felt the statement was. The results indicated that all the negative captions had lower ratings: Man + Woman, M=2.53, SD=2.24; Woman + Child, M=3.75, SD=2.87 and Sportswoman, M=6.15; SD=2.19, than positive captions Man + Woman, M=5.70, SD=2.63; Woman + Child, M=6.05, SD=2.23 and Sportswoman, M=7.62; SD=1.98. Therefore, we used these pictures and captions in the study.

Measures

Person Depicted

Ratings for Person Depicted were obtained for each picture (see Appendix C). For instance, for the first picture in which a man is pointing his finger towards a woman, the participants were required to answer, “How would you rate your feelings towards the man?” Possible responses were from 0 (highly unfavorable) to 10 (highly favorable), and we obtained a response for individuals depicted in each photograph: Man + Woman, Woman + Child and Sportswoman.

Social Dominance Orientation (SDO)

SDO was assessed using six items from the SDO scale (see Appendix A). Participants rated the extent to which they agreed with each item on a 7-point Likert scale, from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The reliability of the SDO scale was unacceptable in the participants from Pakistan, α = .548, and deletion of any item did not raise the alpha. In contrast, the alpha was acceptable in the sample from the USA, α = .779, although item 6 was negatively correlated with the rest of the scale. When dropped, the alpha improved to .835, so we used the shortened 5-item SDO scale for American participants and did not analyze SDO in the participants from Pakistan.

Right Wing Authoritarianism (RWA)

RWA was assessed with six items from the RWA scale (Altemeyer, 1998, see Appendix A). Again, the reliability of the RWA scale was unacceptable in the participants from Pakistan, α = .498, and as for SDO, deletion of any item did not raise the alpha to an acceptable level. In contrast, the alpha was acceptable in the sample from the USA, α = .701, and all items were positively correlated with the overall scale. Therefore, as for SDO, we examined RWA in the American but not the Pakistani participants. The Americans had a mean RWA of 1.10; SD = 0.77, and a mean SDO of 1.07; SD = 1.03. The RWA and SDO scales in the American participants were positively correlated, r = .406, p < .001.

Results

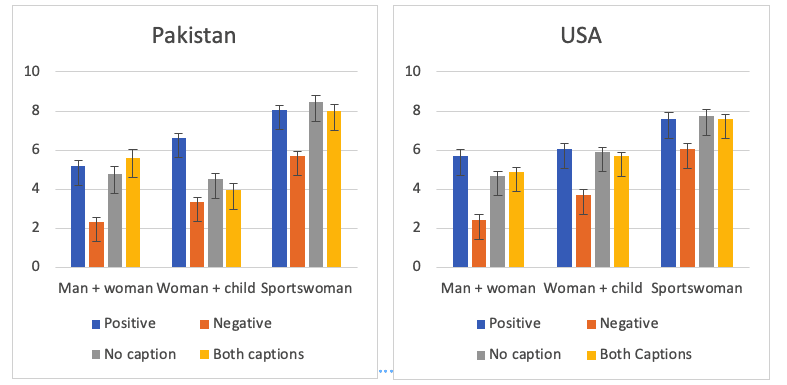

An exploratory analysis of the dependent variables (ratings for Man + Woman, Woman + Child, and Sportswoman) was conducted to identify any outliers in Pakistan and USA. The analysis indicated that there were four outlier data points for Sportswoman amongst the USA sample (i.e., 2 times the interquartile range from the lower quartile). These outliers were retained because a careful inspection of the 5% Trimmed Mean showed that these scores did not have a strong influence on the mean. Figure 4 shows the descriptive statistics for the main variables, that is, they show the Ratings for Person Depicted in each picture by Experimental Group for each country.

Figure 4: Person Rating for each Picture by Experimental Group in Pakistan and USA

*Higher ratings indicate a more positive response

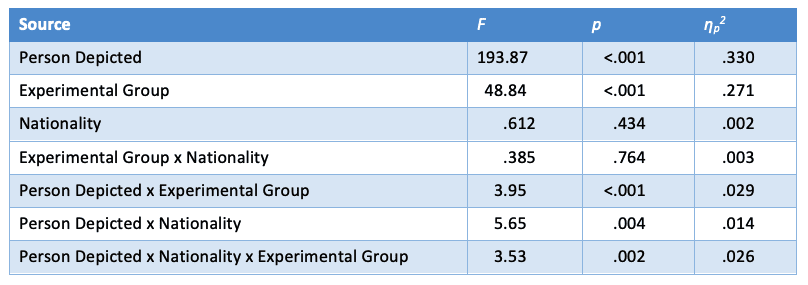

To examine this data, we used a 4 (Experimental Group: negative, positive, none, both) x 2 (Nationality: American, Pakistani) x 3 (Person Depicted) mixed analysis of variance ANOVA. Experimental Group and Nationality were between-subjects variables and the Person Depicted was within-subjects. The dependent variable was rating towards each pictured person (from 0 to 10). The results of this analysis are presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Summary of Effects from Mixed Measures ANOVA with Person Depicted Ratings as Dependent Variable

There were main effects for Person Depicted and Experimental Group. Three interactions were also significant, including the two-way interaction between Person Depicted and Experimental Groups, the two-way interaction between Person Depicted and Nationality, and the three-way interaction between Person Depicted, Nationality and Experimental Group.

To understand the three-way interaction, we first examined Figure 4. It suggested that the trends in ratings for a person in the Positive and Negative Captions conditions were similar across the three pictures in that positive caption groups had higher ratings than negative caption groups. This was a consistent finding across all three pictures in both countries. Regarding the control groups (no caption and both captions), those in the USA had ratings closer to the positive caption condition ratings for all three pictures, whereas in Pakistan, for the Woman + Child picture, the control group ratings were closer to the negative caption condition ratings. Therefore, in the next step, we used multivariate analysis using the ratings for Person Depicted to examine whether the Nationality x Group interaction was significant for each Person Depicted. For the Man + Woman picture, the interaction was not significant, F (3, 392) = .842, p = .471, η2p = .006. Similarly, for the Sportswoman picture, the interaction was not significant, F (3, 392) = 1.03, p = .380, η2p = .008. However, for the Woman + Child picture, the interaction was significant, F (2, 392) = 4.03, p = .008, η2p = .030. For the Woman + Child picture, the participants from Pakistan rated the Both and No Captions conditions similar to the Negative Caption condition, whereas the participants from the USA rated the Both and No Captions conditions similar to the Positive Caption condition. In other words, participants from Pakistan had generally lower ratings for the Woman + Child compared to those from the USA. Given that we were not particularly interested in effects for individual pictures, we did not pursue this effect further.

Instead, we had a major interest in the effect of a positive versus a negative caption. To this end, examination of Figure 4 indicated that the difference in ratings on the Positive versus Negative Captions conditions was similar across the three pictures. Therefore, we dropped the Both Captions and No Captions conditions and carried out a 2 (Experimental Group: negative, positive) x 2 (Nationality: American, Pakistani) x 3 (Person Depicted) mixed measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). In this case, the three-way interaction was not significant, F (2, 286) = 0.39, p = .676, p2 = .003, and neither were any of the other effects, all Fs < 2.38, all ps > .125, with the exception of the effect for Person Depicted, F (2, 286) = 44.50, p < .001, p2 = .237, and that for Experimental Group, F(1, 143) = 31.34, p < .001, η2p = .180. Therefore, we examined the effect for Person Depicted ratings using paired-samples t-tests. Ratings were higher for the Sportswoman picture (M = 7.38, p = 2.03) than the Woman + Child picture (M = 5.86, p = 2.37), t (146) = 7.37, p < .001, for the Sportswoman picture than the Man + Woman picture (M = 5.16, p = 2.52), t(146) = 9.07, p < .001, and for the Woman + Child picture than the Man + Woman picture, t(146) = 3.02, p = .003.

Finally, we examined the effect for the Experimental Group with an independent-samples t-test collapsing across Nationality. The results of this analysis indicated a significant difference between Positive and Negative conditions for all three pictures, Man + Woman, t (199) = 8.31, p<.001; Woman + Child, t (199) = 7.26, p<.001; Sportswoman, t (199) = 5.58, p<.001). Figures 4.1 and 4.2 indicated that the positive caption group resulted in higher ratings whereas the negative caption group resulted in lower ratings towards the pictured individual for each picture in both countries. We also re-checked these results using nonparametric testing which yielded the same results.

In Pakistan, A Mann-Whitney test indicated that outcome ratings for Man + Woman were higher for the positive caption group (Mdn =58.85) than for the negative caption group (Mdn =34.15), U=490.0, p <.001; similarly for Woman + Child, ratings were higher for positive caption group (Mdn =59.35) than for the negative caption group (Mdn =33.65), U=467.0, p <.001 and finally the same pattern was observed for Sportswoman, whereby ratings were higher for positive caption group (Mdn =56.48) than for the negative caption group (Mdn =36.52), U=599.0, p <.001

In the USA, the same results were found whereby, outcome ratings for Man + Woman were higher for the positive caption group (Mdn =72.45) than for the negative caption group (Mdn =36.57), U=507.0, p <.001. The same was true for Woman + Child, positive caption group (Mdn =67.41) was higher than negative caption group (Mdn =41.89), U=789.0, p <.001 and finally for Sportswoman, positive caption group (Mdn =66.32) was higher than negative caption group (Mdn =43.04), U=850.0, p <.001. The reason for using parametric testing was that it allowed for a more detailed understanding of the phenomenon. However, since some of the data did not meet the assumptions for normality, it was essential to check using non-parametric testing to ensure accuracy

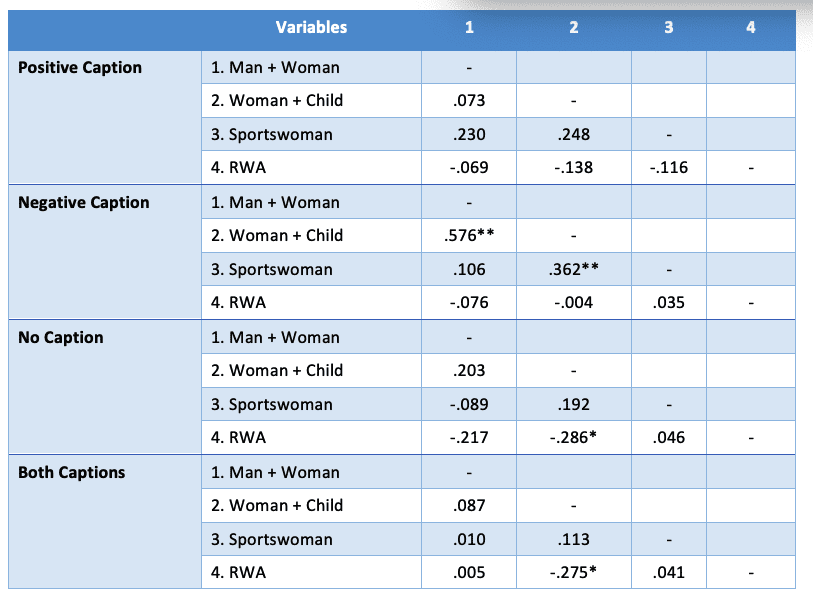

Next, we explored the correlation between SDO, RWA and American participants’ feelings toward the individuals depicted in the three pictures. (Recall that the alphas were unacceptable for both RWA and SDO in Pakistan.). To understand how each picture rating related to RWA and SDO, we used Spearman’s rho correlation analysis (since RWA and SDO were non-normally distributed). The results indicated that only Woman + Child picture ratings correlated negatively with RWA, r=-.136, p=.04). Less interestingly, there were also correlations between picture ratings, including Sportswomen and Woman + Child, r=.410, p<.001, Sportswoman and Man + Woman, r=.194, p=.004, and that between Woman + Child and Man + Woman, r=.351, p<.001.

The ANOVA presented above indicated that there was an effect of the experimental group on picture ratings. Therefore, we explored correlations between RWA and person rating separately in each experimental group (Table 2).

Table 2: Correlations Between Person Depicted, SDO and RWA in Each Experimental Group

Note. *p<.05, **p<.001.

There were no significant correlations with RWA for the Positive or Negative Caption groups, but for the No Caption and Both Captions groups, RWA correlated negatively with ratings on the Woman + Child picture such that higher RWA was associated with less favorable ratings. In sum, the correlations with RWA indicated that when the media did not bias participants’ interpretation of the pictures in one direction only (in the Both Captions and No Captions conditions), higher RWA had some relation to a less favorable interpretation, demonstrating the role of ideological beliefs in person/picture perception. Thus, there is a role for both ideological beliefs and headlines in influencing picture interpretation (recall the effect for condition in the ANOVA above, indicating more favorable ratings in the Positive versus the Negative condition).

These findings raise the question of whether positive or negative captions would influence person perception independent of RWA. In other words, would individuals of high RWA respond differently to caption manipulation than those who score low on RWA? To understand this question, we used an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with the American group (since RWA was not reliable in Pakistanis). More specifically, we used a 2 (Experimental Group: negative headline, positive headline) x 3 (Person Depicted) mixed measures ANCOVA, with RWA as the covariate, and the three ratings for pictured persons as the dependent measures. The main interest was in whether the effect for Group would still be significant. It was, F (1, 84) = 37.80, p < .001, p2 = .310. This result indicates that the presence of a positive versus a negative caption influenced picture interpretation independent of ideological beliefs.

Taken together, these results indicate that media manipulation (as measured by the experimental group) can be a significant predictor for an emotional response towards unknown individuals of color presented in ambiguous pictures. The ANCOVA results further this finding by suggesting that experimental group assignment is more important than ideological beliefs (RWA), at least when people in ambiguous pictures are being rated.

Discussion

For picture captions, the results indicated that positive and negative captions, when presented on their own, affected the emotional response towards a pictured person in a predicted direction. However, when a positive caption was presented alongside a negative one (such as in the Both Captions group), it resulted in more favorable ratings than a negative caption on its own. Thus, the mere presence of a positive caption along with a negative caption seemed to open peoples’ minds to a less negative interpretation of the picture. Additionally, the No Caption condition and Both Captions condition ratings were closer to the Positive Captions rating (except for Woman + Child in Pakistan), which suggested that in the absence of any cue or when two contradictory descriptions are presented, participants tend to rate individuals more positively. These findings are useful in understanding how picture captions circulating in the media might influence a viewer’s emotional response. For instance, regarding issues pertaining to immigrants and Muslims, even a brief exposure to a negative description may lower feelings towards the pictured person.

The present study also indicated that RWA may have a role in person perception. When captions do not bias the viewer in one direction only (such as in the No Caption and Both Captions groups), there was a relation between RWA and person ratings. Without the presence of external cues or when two contradictory views were presented, American individuals appeared to rely more on their ideological beliefs. This finding is in line with prior research that suggests there is a positive correlation between RWA and ethnic prejudice (Altemeyer, 1988; Heaven, 2001; Nesdale, De Vries, Robbé, & Van Oudenhoven, 2012).

We also noted that when compared to the effect of caption manipulation, the effect of RWA was small, and there was a greater effect for positive versus negative headlines in the American sample, and an effect for caption manipulation in both countries across all three pictures immediately after exposure. The results of this experiment indicate that regardless of whether participants viewed ingroup or outgroup members, they were equally influenced by a brief but strongly valenced picture caption. This finding was contrary to my expectation as we had expected Pakistani participants to rate certain pictures more positively than the American participants, but the absence of effects for Nationality indicated that there were no differences between how Pakistani and American participants were rating these unknown individuals.

The finding that biased captions had a greater influence in rating the person depicted regardless of their ideological beliefs right after exposure is important given that biased media (e.g., that negatively portrays immigrants) may cause intergroup anxiety, lead to the belief that this group of people is less deserving, and ultimately, result in stricter immigration policies (Atwell & Mastro, 2016). Further, this cycle may also increase a minority group’s negative feelings towards the majority group (Tsfati, 2007), therefore widening the intergroup gap and creating friction within societies. Clearly, a brief positive media exposure is effective when employed to represent outgroup members and may foster more accepting feelings toward diverse ethnic groups.

All in all, our results indicate that even a brief media exposure to biased picture captions may significantly alter the viewer’s emotional response towards the pictured individual in a predicted direction immediately after exposure. This is especially true when the viewer is presented with only one caption suggesting a single interpretation of the ambiguous picture (as opposed to no caption or two alternate captions) and is important given the increasing tendency for news media to present biased views of news stories (Morris, 2005; Prior, 2013). Further, we note again Prior’s conclusion that there is no firm evidence that a biased media makes individuals more biased. Captions are one component of a biased media and our findings indicate a clear and immediate effect on subsequent attitudes. In addition, these effects occurred with random assignment to conditions. As such, even if in real-life settings individuals seek and follow the content that closely matches their own belief system, they will likely be affected by biased captions at times. Future research should continue to explore how repeated exposure to captions and text skewed in one direction bias attitudes toward outgroup members and issues.

References

Ahmed, S. (2017). News media, movies, and anti-Muslim prejudice: investigating the role of social contact. Asian Journal of Communication, 27(5), 536–553. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2017.1339720

Altemeyer, B. (1998). The Other “Authoritarian Personality.” Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 47–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0065-2601 (08)60382-2

Atwell Seate, A., & Mastro, D. (2016). Media’s influence on immigration attitudes: An intergroup threat theory approach. Communication Monographs, 83(2), 194–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2015.1068433

Banas, J. A., Bessarabova, E., & Massey, Z. B. (2020). Meta-Analysis on Mediated Contact and Prejudice. Human Communication Research, 46(2-3), 120–160. doi:10.1093/hcr/hqaa004

Barthes, R. (1977). ‘Rhetoric of the image’, In R Barthes (ed.), Image, music, text, Fontana: London.

Batziou, A. (2011). Framing “otherness” in press photographs: The case of immigrants in Greece and Spain. Journal of Media Practice, 12(1), 41–60. https://doi.org/10.1386/jmpr.12.1.41_1

Bleiker, R., Campbell, D., Hutchison, E., & Nicholson, X. (2013). The visual dehumanisation of refugees. Australian Journal of Political Science, 48(4), 398–416. doi:10.1080/10361146.2013.840769

Brosch, T., Bar-David, E., & Phelps, E. A. (2013). Implicit race bias decreases the similarity of neural representations of black and white Faces. Psychological Science, 24, 160–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612451465

Bryant M (1996) Photo-Textualities: Reading Photographs and Literature. Newark: University of Delaware Press.

Crawford, J. T., Jussim, L., Cain, T. R., & Cohen, F. (2013). Right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation differentially predict biased evaluations of media reports. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43(1), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.00990.x

Darling-Wolf F, Mendelson AL (2008) Seeing Themselves through the Lens of the Other: An Analysis of the Cross Cultural Production and Negotiation of National Geographic’s ‘The Samurai Way’ Story. Journalism & Communication Monographs 10(3): 285–322. doi:10.1177/152263790801000303

Davies, B., Turner, M., & Udell, J. (2020). Add a comment … how fitspiration and body positive captions attached to social media images influence the mood and body esteem of young female Instagram users. Body Image, 33, 101–105. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.02.009

Dixon, T. L. (2008). Crime News and Racialized Beliefs: Understanding the Relationship Between Local News Viewing and Perceptions of African Americans and Crime. Journal of Communication, 58(1), 106–125. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460- 2466.2007.00376.x

Dragojevic, M., Sink, A., & Mastro, D. (2016). Evidence of Linguistic Intergroup Bias in U.S. Print News Coverage of Immigration. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 36(4), 462–472. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927×16666884

Entman, R. M. (1991). Framing U.S. Coverage of International News: Contrasts in Narratives of the KAL and Iran Air Incidents. Journal of Communication, 41(4), 6–27. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1991.tb02328.x

Esses, V. M., & Hodson, G. (2006). The Role of Lay Perceptions of Ethnic Prejudice in the Maintenance and Perpetuation of Ethnic Bias. Journal of Social Issues, 62(3), 453–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2006.00468.x

Fahmy, S. (2004). Picturing Afghan Women: A Content Analysis of AP Wire Photographs During the Taliban Regime and after the Fall of the Taliban Regime. Gazette (Leiden, Netherlands), 66(2), 91–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016549204041472

Farris, E. M., & Silber Mohamed, H. (2018). Picturing immigration: how the media criminalizes immigrants. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 6(4), 814–824. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2018.1484375

Fuochi, G., Voci, A., Veneziani, C. A., Boin, J., Fell, B., & Hewstone, M . (2019). Is negative mass media news always associated with outgroup prejudice? The buffering role of direct contact. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 23 (2), 195-213. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430219837347

Gamson, W. A., & Modigliani, A. (1989). Media Discourse and Public Opinion on Nuclear Power: A Constructionist Approach. American Journal of Sociology, 95(1), 1–37. doi:10.1086/229213

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. Harvard University Press.

Hamborg, F., Donnay, K., & Gipp, B. (2018). Automated identification of media bias in news articles: an interdisciplinary literature review. International Journal on Digital Libraries, 20(4), 391–415. doi:10.1007/s00799-018-0261-y

Heaven, P. C. L. (2001). Prejudice and personality: The case of the authoritarian and social dominator. In M. Augoustinos & K. J. Reynolds (Eds.), Understanding prejudice, racism, and social conflict (pp. 89–106). London: Sage.

Ho, A. K., Sidanius, J., Kteily, N., Sheehy-Skeffington, J., Pratto, F., Henkel, K. E., Foels, R., & Stewart, A. L. (2015). The nature of social dominance orientation: Theorizing and measuring preferences for intergroup inequality using the new SDO7 scale. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109, 1003-1028. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000033

Holmes, E. A., Mathews, A., Mackintosh, B., & Dalgleish, T. (2008). The causal effect of mental imagery on emotion assessed using picture-word cues. Emotion, 8, 395-409. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.8.3.395

Instagram. (2019). Stats. Accessed online (March 19, 2019) at https://www.instagram.com/press/.

Iyer, A., Webster, J., Hornsey, M. J., & Vanman, E. J. (2014). Understanding the power of the picture: the effect of image content on emotional and political responses to terrorism. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 44(7), 511–521. doi:10.1111/jasp.12243

Kerrick, J. S. (1959). News pictures, captions and the point of resolution. Journal. Mass Communication Quarterly, 36, 183–188. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/107769905903600207

Kobre, K. (2008). Photojournalism: The professionals’ approach. Oxford, UK: Taylor Francis Ltd.

Lee, E. J. (2019). Traditional and New Media. International Journal of Interactive Communication Systems and Technologies, 9(1), 32–47. doi:10.4018/ijicst.2019010103

Lee, Y.-H., & Chen, M. (2020). Emotional Framing of News on Sexual Assault and Partisan User Engagement Behaviors. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly. doi:10.1177/1077699020916434

Mehling, R. (1959). Attitude changing effect of news and photo combinations. Journalism Quarterly, 36, 189–198. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/107769905903600208

Messaris, P., & Abraham, L. (2001): The role of images in framing news stories. In S.D. Reese, O. H. Gandy & A. E. Grant (Eds.), Framing public life: perspectives on media and our understanding of the social world (pp. 215-226). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Mikkleson, D. (1 September, 2005). Were Hurricane Katrina ‘Looting’ Photographs Captioned Differently Based on Race? Retrieved from https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/hurricane-katrina-looters/ on 26 July, 2020.

Morris, J. S. (2005). The Fox News factor. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 10(3), 56-79. doi: 10.1177/1081180X05279264

Nesdale, D., De Vries Robbé, M., & Van Oudenhoven, J. P. (2012). Intercultural Effectiveness, Authoritarianism, and Ethnic Prejudice. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 42(5), 1173–1191. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2011.00882.x

Nickerson, C. (2019). Media portrayal of terrorism and Muslims: a content analysis of Turkey and France. Crime, Law and Social Change, 72(5), 547–567. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-019-09837-6

Nurullah, A. S. (2010). Portrayal of Muslims in the media: “24” and the ‘Othering’ process.International Journal of Human Sciences, 7(1), 1020-1046. Retrieved from https://www.j-humansciences.com/

Ogan, C., Willnat, L., Pennington, R., & Bashir, M. (2013). The rise of anti-Muslim prejudice: Media and Islamophobia in Europe and the United States. International Communication Gazette, 76, 27–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048513504048

Parrott, S., Hoewe, J., Fan, M., & Huffman, K. (2019). Portrayals of Immigrants and Refugees in U.S. News Media: Visual Framing and its Effect on Emotions and Attitudes. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 63(4), 677–697. doi:10.1080/08838151.2019.1681860

Persson A. V. Musher-Eizenman D. R. (2005). College students’ attitudes toward Blacks and Arabs following a terrorist attack as a function of varying levels of media exposure. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 35,1879–1892.

Pfau, M., Haigh, M., Fifrick, A., Holl, D., Tedesco, A., Cope, J., . . . Martin, M. (2006). The effects of print news photographs of the casualties of war. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 83, 150–168. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/107769900608300110

Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., Stallworth, L. M., & Malle, B. F. (1994). Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 741–763. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.4.741

Prior, M. (2013). Media and political polarization. Annual Review of Political Science, 16, 101-127. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-100711-135242

Sacchi, D. L. M., Agnoli, F., & Loftus, E. F. (2007). Changing history: doctored photographs affect memory for past public events. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 21(8), 1005–1022. doi:10.1002/acp.1394

Shaver, J. H., Sibley, C. G., Osborne, D., & Bulbulia, J. (2017). News exposure predicts anti- Muslim prejudice. PLOS ONE, 12(3), e0174606. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174606

Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (2001). Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/ 10.1017/CBO9781139175043

Smith, K. (2019, January 5). 53 Incredible Facebook Statistics and Facts. Retrieved from https://www.brandwatch.com/blog/facebook-statistics/

Stanley, S. K., Milfont, T. L., Wilson, M. S., & Sibley, C. G. (2019). The influence of social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism on environmentalism: A five-year cross-lagged analysis. PloSONE, 14, e0219067. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0219067

Stanovich, K. E., & West, R. F. (2000). Individual differences in reasoning: Implications for the rationality debate? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 23(5), 645–665. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0140525x00003435

Staples, R. (2011). White Power, Black Crime, and Racial Politics. The Black Scholar, 41(4), 31–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/00064246.2011.11413574

Strube, M. J., & Rahimi, A. M. (2006). “Everybody knows it’s true”: Social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism moderate false consensus for stereotypic beliefs. Journal of Research in Personality, 40, 1038-1053. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2005.10.004

Tajfel, H. (1982). Experimental Studies of Intergroup Behaviour. Cognitive Analysis of Social Behavior, 227–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-7612-2_8

Tsfati, Y. (2007). Hostile Media Perceptions, Presumed Media Influence, and Minority Alienation: The Case of Arabs in Israel, Journal of Communication, 57(4), 632–651. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2007.00361.x

Wright, C., Brinklow-Vaughn, R., Johannes, K., & Rodriguez, F. (2020). Media Portrayals of Immigration and Refugees in Hard and Fake News and Their Impact on Consumer Attitudes, Howard Journal of Communications, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10646175.2020.1810180

Zhang, Q. (2010). Asian Americans Beyond the Model Minority Stereotype: The Nerdy and the Left Out. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication, 3(1), 20–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/17513050903428109