Applying an Attitude Change Theory in an Eastern Setting

Leo Chan, Ph.D.

Communication Program/Digital Media Studies

University of Houston – Clear Lake

Abstract:

Abstract:

Compared to the United States, there is a lack of media education in Asian countries (Shih, 1999). Hong Kong has no experience with media education projects for children, parents or teachers. The western critical viewing skills project, “Taking Charge of Your TV,” appears to have been a useful tool for parents searching to take control of the family television and trying to talk to their children about television violence in the United States. The purpose of this study was to carry this viewing skills project to Hong Kong, testing whether it might benefit families there as well. The broader objective was to examine how well a Western media education instrument, the critical viewing skills project, could be applied in the Hong Kong media environment.

Leo Chan earned his Ph.D in Mass Communication and Media Arts. His dissertation focused on intercultural communication, media effects, and children’s television programming. Chan, a native from Hong Kong, is currently an Assistant Professor in the Communication Program and Digital Media Studies at University of Houston – Clear Lake. His convergence of experiences in mass communication and media arts have stimulated his teaching and research interests in media effects, media and society, multimedia design, intercultural communication, visual communication, and international media. He was also nominated for the university wide teaching award in 2004. In addition to his full time teaching position, Chan has been active in research that has resulted in a number of conference presentations nationally and internationally, and more are currently out on review. He enjoys both activities immensely. He was also involved in the Big Brothers and Big Sisters as a big brother for two years. chanta@uhcl.edu

Leo Chan earned his Ph.D in Mass Communication and Media Arts. His dissertation focused on intercultural communication, media effects, and children’s television programming. Chan, a native from Hong Kong, is currently an Assistant Professor in the Communication Program and Digital Media Studies at University of Houston – Clear Lake. His convergence of experiences in mass communication and media arts have stimulated his teaching and research interests in media effects, media and society, multimedia design, intercultural communication, visual communication, and international media. He was also nominated for the university wide teaching award in 2004. In addition to his full time teaching position, Chan has been active in research that has resulted in a number of conference presentations nationally and internationally, and more are currently out on review. He enjoys both activities immensely. He was also involved in the Big Brothers and Big Sisters as a big brother for two years. chanta@uhcl.edu

Introduction

Hong Kong is a meeting place for Eastern and Western cultures. On one hand, Hong Kong is a city that absorbs influences from the West and localizes foreign cultures; on the other hand, Hong Kong is a Chinese community that has strong links with Chinese traditions and culture. This study attempts to determine if it is possible to apply a Western media education instrument in the Hong Kong setting. Specifically, this study is a test of whether children in Hong Kong can be taught critical viewing skills for television violence in the Western-style project “Taking Charge of Your TV.”

Over the years a special segment of the television audience has been a focus of research attention: children. Many studies have examined issues of both positive and negative learning outcomes from viewing television programs (Johnson, 2001). In the United States, children spend more time watching television than in the classroom, taking part in outdoor activities, or reading (Huston, Donnerstein, Fairchild, Feshback, Katz, Murray, Rubinstein, Wilcox, & Zuckerman, 1992). By the time an average American child finishes elementary school, he or she will have watched more than 8,000 murders and more than 100,000 other acts of violence on network television (Huston et al., 1992).

In Hong Kong, television is dominant among all media in reaching the public on a regular basis. According to a survey conducted by the Hong Kong Federation of Youth Groups (Wong, 2000), almost 84 percent of the respondents between 15 and 39 believe that there is too much violence on television.

Regarding the presence of violence in television programming, attitude change theory has been developed in attempts to lower the harmful influence of television on viewers. Attitude change is said to occur when subjects receive new information from other people or media through direct experience with the attitude object, and this forces the subjects to behave in a way different than they used to. Attitude is an idea charged with emotion that predisposes an action to a particular social situation (Triandis, 1971).

The application of attitude change to media studies is the notion that parents change their attitudes toward television violence and protect children from potentially harmful television violence by being educated about and prepared for this influence in advance. Children then can resist the effects of television violence after they learn how to recognize it and practice skills they learned from their parents.

Previous research has shown that teaching children critical TV viewing skills can make them aware of the harmful effects of TV violence in the United States (Singer & Singer, 1983; Watkins, Sprafkin, Gadow, & Sadetsky, 1988). Training parents to acquire critical TV viewing skills includes informing them of the negative effects TV violence can have on their children and teaching them how to counteract these potential negative effects. Parents might then teach their children how to be critical TV viewers (Tangney & Feshback, 1988).

In the United States, the National Parent Teacher Association (National PTA) led to help educate parents to take control of television within homes since 1994 and developed a critical viewing skills workshop called “Taking Charge of Your TV,” aimed at providing parents and teachers with a better understanding of the effects of television on children.

Compared to the United States, there is a lack of media education in Asian countries (Shih, 1999). Hong Kong has no experience with media education projects for children, parents or teachers. The critical viewing skills project, “Taking Charge of Your TV,” appears to have been a useful tool for parents searching to take control of the family television and trying to talk to their children about television violence in the United States. The purpose of this study was to carry this viewing skills project to Hong Kong, testing whether it might benefit families there as well. The broader objective was to examine how well a Western media education instrument, the critical viewing skills project, could be applied in the Hong Kong media environment.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Studies on Media Violence in the West

The relationship between television violence and real-life aggression has been a controversial topic. Many researchers argue that there is a strong association between viewing violence and behaving aggressively (Van Evra, 1998). Some research has shown a positive correlation between exposure to TV violence and aggressive behavior over many different kinds of measures and ages, and exposure seemed to increase violence (Donnerstein, Slaby, & Eron, 1994).

Children often do not have the capacity to distinguish between reality and fiction and they take for granted what they see on television, thus stimulating their own aggression (Singer & Singer, 1990). If they are repeatedly exposed to messages that promote the idea that violence is fun or is appropriate in solving problems and accords status, then the risk that they learn these attitudes and behavior patterns becomes very high (Groebel, 2001).

A study by the Annenberg School of Communication found that television violence reached up to 32 violent acts per hour in children’s programming. TV Guide found 1,845 violent acts in 18 hours of viewing, an average of 100 an hour or one every 36 seconds (Lamson, 1995).

In one study, randomly chosen children were shown either a violent or nonviolent short film, and then they were observed as they played with each other or with objects such as Bo-Bo dolls. The consistent finding was that children who watched violent acts behaved more aggressively immediately afterward. The same effect occurred for all children regardless of their gender and ethnicity (Josephson, 1987).

Attitude Change: Theoretical Approach

As the purpose of this study was to determine if the “Taking Charge of Your TV” workshop helped parents minimize the negative influence of television violence on children, it was important to look at the participants’ attitudes toward the workshop and how the workshop changed their behavior after attending the workshop.

The attitude construct continues to be a key focus of theory and research in the social and behavioral sciences (Wood, 2000). Thurstone (1931) defined attitude as effect for or against a psychological object; early theorists used affect in the sense in which we now refer to attitude (Ajzen & Fishbein, 2000). Attitudes are defined as a mental predisposition to act that is expressed by evaluating a particular entity with certain degree of favor or disfavor. Attitudes are comprised of four different components: cognitions, affect, behavioral intentions, and evaluation (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980).

Attitudes change when participants receive new information from other people or media through direct experience with the attitude object, and that force them to behave in a way different than they used to (Triandis, 1971).

This study aimed to study the effectiveness of the “Taking Charge of Your TV” workshop in Hong Kong by looking at the participants’ attitudes and behavior after attending the workshop. Participants were introduced to the key concepts with suggestions based on the material prepared by the National PTA. The cognitive component was established when the concepts of “Taking Charge of Your TV” were presented to the participants in Hong Kong. Participants showed their understanding of the concepts of the workshop as representing the cognitive component.

Regarding the affective component of attitude theory, participants showed their positive or negative perceptions of the concepts presented in the workshop. They responded to the workshop according to their feelings, and they turned their feelings into personal belief. The participants then responded to the workshop by actually taking actions as representing the behavioral component. If the participants strongly believed in what they learned in the concept, the assumption was, they would be more likely to practice the concepts at home more frequently.

Co-viewing with Parents

The critical viewing skills project, “Taking Charge of Your TV,” is based on the premise that parents watching television with their children is important. Parents are in the best position to discuss the potentially harmful effects of television violence with their children at home (Bushman & Huesmann, 2001).

According to Tangney and Feshback (1988), there was evidence to show that the effects of viewing violence could also be reduced by the parents’ co-viewing with the child. Fred Rogers, the host of a famous children’s show “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood,” believed that parents could help children distinguish between fantasy and reality. They could help children identify and manage their feelings, and encourage children to talk about those feelings with the real-life adults they loved and trusted (Rogers, 2001).

Development of Media Education

Media education creates competent and critical users. The major stress should not be on how to get children to avoid television, but how to use television for entertainment and for constructive goals (Groebel, 2001). In the 1970s, a television curriculum was introduced into American schools in an effort to encourage and develop children’s critical viewing skills and television literacy. Many media literacy and critical viewing skills programs have been developed since then. (Van Evra, 1998).

By the late 1990s, some 15 states required some form of media study as part of the general curriculum for public schools (Hobbs, 1998). Over the decades, individual teachers, researchers, and academics as well as private organizations, have explored ways to help media users develop more thoughtful interaction with media (Brown, 2001).

Research results suggested that positive developments took place in young children’s use of television after various kinds of training in critical viewing or media literacy, and development of cognitive skills related to television use (Brown, 2001).

Critical Viewing Skills, “Taking Charge of Your TV”

The “Taking Charge of Your TV” workshop project trains cable and PTA leaders nationwide in the key elements of critical viewing, and how to present “Taking Charge of Your TV” workshops for parents, educators, and organizations in their communities. Since the launch of the project in 1994, training workshops have taken place in almost all 50 states. More than 4,000 PTA members and cable leaders have been trained; as a result, more than 1,800 workshops for thousands of parents, educators, and community members have been offered throughout the United States.

The project was awarded the National Parents’ Day Clarion Award for using television to promote responsible parenting and the Entertainment Industries Council’s Prism Award (National PTA, 2001).

Background of Hong Kong

Any discussion of Hong Kong must include references to the Handover of Hong Kong. Hong Kong was a British colony until the expiration in 1997 of a 99-year lease. The Handover of Hong Kong is a key event in recent Chinese history. The Sino-British Joint Declaration signed in 1994 by Britain’s Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, and China’s Prime Minister, Zhao Ziyang, guaranteed that Hong Kong would retain a high degree of autonomy for the fifty years following 1997 (Buckley, 1997). It implies that China is not to determine the political, economic, and social institutions and policies of Hong Kong. The people of Hong Kong were promised that they would rule Hong Kong without interference from China, save in matters of security and diplomacy, and that they would continue to enjoy their former way of life in political, economic, and social affairs (Newman & Rabushka, 1998).

While Hong Kong was a colony under British rule, residents enjoyed Western-style personal freedoms, including freedom of expression, which were guaranteed by law. Under the British, diversified mass media were permitted to flourish and represented the entire political spectrum, from newspapers on the left, supported by China, to the newspapers on the right, supported by Taiwan. In the center, there were mass media run by Hong Kong (Davison, 1974).

Even though Hong Kong has been experiencing a transition since 1997, direct intervention from the government is not likely to undermine freedom of expression in the mass media in Hong Kong (Hutcheon, 1998). For example, the television industry fits within the economic structure, favoring private enterprise and free trade without much restriction.

Hong Kong is a very family-oriented society with extended families that provide internal support for the family members. In other words, people in Hong Kong spend a lot of time with family and hold strong family ties. It is also Chinese tradition that people value the time they spend with their family.

Compared to the United States, outdoor activities are scarce in Hong Kong. Due to very limited space in Hong Kong, not many people own property with yards. Some indoor activities are especially popular, such as karaoke singing and watching television. On average, people spend about 3-4 hours per day watching television in Hong Kong (Hong Kong Annual Digest of Statistics, 2000). Hong Kong is a very fast-paced and over-crowded modern society. About 50 percent of the total population lives in public housing (Hong Kong Annual Report, 2000). It is also an important tradition that the whole family comes home for dinner. One of the major activities at home in the evening is watching television together (Ma, 1999).

Media Study in Hong Kong

Television has been the dominant medium in Hong Kong since the 1970s. The high penetration of television has snatched a major audience share from all other forms of media, including movie-going and newspapers (Ma, 1999). People in Hong Kong rely on television as a central source of information and entertainment. On average, Hong Kong residents watch more than three hours of television every day, making it a more popular leisure activity than seeing movies, surfing the Internet, listening to radio, or singing karaoke. It is not unusual that the television is on during the dinner time.

The television industry in Hong Kong is very competitive and fits within the economic structure of the territory, favoring private enterprise and free trade. All of the television stations are commercial. There are two commercial stations offering four free-to-air commercial channels funded by advertising. The two commercial stations are Television Broadcasts Limited (TVB) and Asia Television Limited (ATV). They are licensed to broadcast one Cantonese and one English language channel each. The most popular programs are drama series, news, music shows, entertainment magazines, and game shows (Wilkins, 2002).

There is also a satellite television station (Star TV), and a cable system (Wharf Cable Limited). However, both satellite television and cable television have not been as successful or popular as free television stations (Yan, 2001).

In one survey carried out in 2001, about 35 percent of respondents considered some programming inappropriate, such as violence and obscene language. About 28 percent of respondents had children aged 15 and below. Among them, 72 percent of those parents usually watch television with their children between 7 p.m. and 10 p.m. (Broadcasting Authority Annual Report, 2001).

For children in Hong Kong, television viewing is one of the most popular after-school activities. According to Chan and Lee (2000), Hong Kong children are so used to turning on the television once they get home from school that they are not concerned about the quality of programming and watch whatever is on. One study showed that 33.6 percent of children watch television on regular basis as an after-school habit without parents’ supervision. Chan and Lee (2000) also mentioned that television is a very important part of children’s life in Hong Kong. The television is turned on when they do their homework or eat their dinner. Unfortunately, many parents in Hong Kong also use television as a baby-sitter if they are not home with their children, and they usually do not get to monitor what their children watch when they are out to work (Chan & Lee, 2000).

Violent acts are easily found in almost any television programming, including cartoons, primetime dramas, situation comedies, movies, commercials, game shows, and music videos.

A survey done by Breakthrough, a youth organization in Hong Kong, showed that viewers between 12 and 16 watched television for about 3.7 hours on average weekdays and about six hours on weekends. Close to 60 percent believed what they saw on television was real (Chan & Lee, 2000). According to another survey conducted by the Hong Kong Federation of Youth Groups (Wong, 2000), about 84 percent of the respondents between 15 and 39 years old believed that there was too much violence on television.

According to Mok (2000), Hong Kong parents and educators are concerned and searching for ways to limit the negative impact of television. Mok suggested that parents should help children develop critical thinking about what they see on television and its effects (Mok, 2000).

The critical viewing skills project developed by the National PTA in the United States seems to help minimize the negative influence of television by teaching families how to make informed choices in the television programs they watch and to improve the way they watch them. It was important to carry this structured critical viewing skills project, “Taking Charge of Your TV,” to Hong Kong to see if it would benefit families there as well. This is an experimental study. Both the control group and the experimental group were randomly selected.

Research Hypotheses

This was an experimental study testing the critical viewing skills project developed in the United States, “Taking Charge of Your TV,” to determine if its effectiveness in the Hong Kong culture at helping parents minimize the negative influence of television violence on children.

Because no such structured critical viewing skills project had been undertaken in Hong Kong before, the first hypothesis was to examine how the participants responded to the workshop. Mean score of the participants’ responses to the workshop were calculated.

H1: The workshop participants’ mean assessment score will be greater than the midpoint after attending the workshop.

This study was to examine if the critical viewing skills project was effective with

parents in Hong Kong. The second hypothesis was to examine if the participants perceived the three major concepts of the workshop to be more important after learning of them in the workshop.

H2: The workshop participants’ mean score will be greater in the post-test measure than in the pretest measure.

Another way to study if the critical viewing skills project worked or not was by comparing the control group participants’ responses to the experimental group participants’ responses.

H3: The workshop participants’ mean score will be greater in the post-test measure than in the control group after attending the workshop.

Demographic information was important as it helped to analyze and identify who participated in the study and assessed the potential for those attributes to affect the outcome of the findings. Therefore, the fourth hypothesis was to examine if the participants’ educational background, age, location of home, and number of television sets at home would affect the responses. In addition, information on the amount of media use and participants’ opinion on effect of television violence on children was collected to determine if they affected the participants’ responses to the workshop.

H4: There will be a positive relationship between the participants’ responses and participants’ demographic characteristics, such as their educational background, age, number of television sets at home, and amount of media use, and participants’ opinion on effect of television violence on children.

METHODS

This was an experimental study to test a Western critical viewing skills project, “Taking Charge of Your TV” in the Hong Kong setting. The project aimed to help parents minimize the negative influence of television violence on children. The workshop was presented to participants who were randomly assigned to an experimental group. The workshop presentation was based on the material designed by the National PTA in the United States. This study used a pretest, post-test, control group design. Questionnaires were distributed to participants to measure changes in attitudes following participation in the “Taking Charge of Your TV” workshop.

Participants

The representative of the Federation of Parent Teacher Associations, Louisa Wong, indicated interest in the study. After several meetings, the project director of the Happy Child Development Project indicated interest in the study as well.

This was an experimental study to test a Western critical viewing skills project, “Taking Charge of Your TV” in the Hong Kong setting; it did not need a large number of participants. While samples for surveys are relatively large, a few hundred and above, experimental samples are relatively small, usually about 15 to 30 in each group. The reason for small samples is that the main issue is whether the treatment is effective (Flora & Logan, 1996; Stone, Singletary, & Richmond, 1999). The participation in this study was voluntary.

Apparatus

To measure the first dependent variable, participants’ opinions about the

workshop, an individual score on attitudinal questions was measured on a seven-point Likert scale including “1,” “2,” “3,” “4,” “5,” “6” and “7.”

Responses were coded so that a “7” indicated a high level of the attitudinal measure, while a “1” reflected a low level of the attitudinal measure. Also, both positive and negative statements were included in order to avoid response sets.

To measure the dependent variable of the perception of the major concepts of the workshop, a Likert scale was applied by providing five response alternatives including “Very Important,” “Important,” “Neutral,” “Somewhat Important,” and “Not Important.”

Questions about the demographic characteristics were also included at the end of questionnaire.

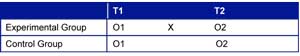

Design

This study was an experimental pretest, post-test, control group design as shown in Figure 1. In this study, there were three dependent variables. The first dependent variable was participants’ opinions about the workshop. The workshop “Taking Charge of Your TV” was the treatment in the study; it was important to first find out how the participants responded to the workshop. The second dependent variable was the participants’ perception of the major concepts of the workshop. The researcher was interested in finding how many critical viewing skills concepts participants knew and understood. Statements based on the workshop concerning the knowledge in workshop concepts constructed the second dependent variable.

Procedure

The researcher prepared for the study by first contacting the National Parent Teacher Association in the United States (PTA) and attended a one-day presenter training course in Chicago organized by the National PTA, the National Cable Television Association, and Cable in the Classroom, to become a qualified workshop presenter. The research also received literature, videotapes, training material, and a brochure on the workshop. The goal of this study was to test the “Taking Charge of Your TV” workshop in Hong Kong. It was therefore essential to present the workshop material in a way that people in Hong Kong could understand it. Therefore, it was necessary to have all the material translated into Chinese.

Participation in the workshop was voluntary. Parents associated with the Happy Child Development Project were randomly assigned as an experimental group and received the treatment. Thirty-seven participants from the Happy Child Development showed up to take part. Before the workshop started, a pre-test questionnaire was handed out to them regarding the concepts of the workshop that would be presented in the workshop.

The workshop was administered based on the material and training supplied by the National PTA. The aim of the workshop was to develop an understanding of three key points for modifying television viewing behavior and applying them to media violence. The first key point presented was that TV programs and their messages were constructed piece-by-piece by production crews and casts to achieve specific results. A video clip was played to stimulate discussion. After the discussion, a few techniques were suggested for participants to practice with their children at home.

The second key point was that different people interpreted TV programs and messages in different ways, based on age, gender, personal identity, and life experiences. This discussion after viewing another video clip was intended to help parents understand the feelings children had at different age levels while watching certain television programs, and enable parents to talk with their children with understanding and good techniques that they learned in the workshop.

The third key point was that television violence could be portrayed in different forms. The video clip of humorous violence was shown after the participants are divided into two groups. Both groups had to defend their viewpoints about humorous violence. Parents could use some techniques presented in this workshop to discuss this issue with their children.

After presenting the three key points, there was a 15-minute discussion session. The researcher made some concluding remarks about the workshop material by saying: “Viewing television should be an active form of entertainment. Talk back to your television. Talk to your children about what they are seeing. Participants were then asked to fill out two sets of questionnaires. The first was about their opinions regarding the workshop. The second referred to their perception of major concepts presented in the workshop.

The control group participants also filled out the second set of questionnaire only as they did not attend the workshop.

RESULTS

The first hypothesis suggested that the participants would respond to the workshop positively with an average score higher than the midpoint, which was 4. The hypothesis for each category was higher than the midpoint, and the overall mean was 5.61. With the highest mean score of 6.1, participants found the workshop highly useful to them. Also, the participants expressed the view that the workshop was relevant, valuable, educational, clear, and informative. According to the results, the participants also felt that the workshop was objective, convincing, interesting, and lively. The first hypothesis was supported by the positive response with the overall mean of 5.61.

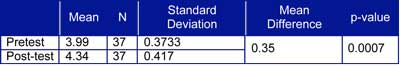

Hypothesis 2 suggested that the workshop participants’ mean score would be greater in the post-test measure than in the pretest measure. A t-test was used to show if the mean score between the pretest and post-test was significantly different.

In the study, the mean of the pretest was 3.99, and the mean of the post-test was 4.34. The p-value was 0.0007. The result indicated that the mean of the post-test scores of the experimental group was significantly higher than the mean of the pretest scores by 0.35 (Table2). The participants of the experimental group perceived the concepts of the workshop to be significantly more important after learning of them in the workshop.

Table 2. Comparison of Pretest and Post-test Mean Scores on Perception of Workshop Concepts

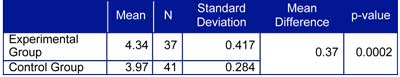

Hypothesis 3 suggested that the workshop participants’ mean score would be greater in the post-test measure than in the control group after attending the workshop. A t-test was used to show a significant difference between the experimental group and the control group scores.

The mean score of the post-test for the experimental group was 4.34, and the mean score of the post-test for the control group was 3.97. The p-value comparing the experimental group and control group was 0.0002, which implied that the test was considered significant at the .05 level. The mean difference between the experimental group and control group was 0.37 (Table 3). Therefore, the result showed that the mean of the post-test scores of the experimental group was significantly higher than the mean score of the control group. Therefore, hypothesis three was upheld.

Table 3. Measuring Experimental and Control Participants’ Perception of Workshop Concepts

Hypothesis 4 suggested that a significant positive relationship would exist between the participants’ perceptions of the importance of the workshop concepts and their demographic characteristics, such as their educational background, age, number of television sets at home, and amount of television viewing, and participants’ opinion on effect of television violence on children. A multiple regression was used to test this hypothesis.

Table 4 showed that a significant relationship was found (F=3.975, p=.011), and the hypothesis was supported. Fifty-eight percent of variance in the dependent variable of the perception of the concepts was explained by the equation. However, only one independent variable, educational level, was significant. Only one independent variable had a unique contribution to explaining the dependent variable. The shared contributions were 34%, and the unique contributions were 6% for education. The test indicated that participants with higher education backgrounds in Hong Kong tended to perceive the concepts of the workshop as important. However, no significant relationship was found between the participants’ perception of the concepts and the variables of the participants’ opinion of effect of television on children and participants’ amount of time watching television.

Table 4. Relationship between Participants’ Responses to the Concepts and Demographics Characteristics

Implications of the Results

In the study, the researcher found that participants in Hong Kong who participated in the “Taking Charge of Your TV” workshop responded positively to the workshop. According to the idea of the affective component based on the attitude theory, participants strongly indicated their positive reactions to the workshop. Overall, the participants were actively involved in the workshop and felt satisfied with what they learned during the workshop. Their positive responses, however, might help promote future workshop presentations to different organizations, and elementary schools for future research.

The researcher also found that the “Taking Charge of Your TV” workshop positively changed the participants’ perceptions regarding the importance of the workshop concepts, supporting the cognitive component of attitude theory (Wood, 2000). As violence on television is a growing concern in Hong Kong, the participants understood how important it was to be critical viewers and help their children modify their television viewing. In the post-test, the mean scores of participants’ perceptions of the workshop became even higher, which indicates that the workshop changed their views about violence on television, and they wanted to pay more attention to this issue at home.

The researcher also found that the experimental group perceived the major concepts presented in the workshop to be more important than did the control group, who had not been exposed to those concepts. This result suggested that the workshop did have some effects on participants regarding the concepts of the “Taking Charge of Your TV” as representing the affective component of the attitude theory (Wood, 2000). In other words, the control group’s perceptions of the major concepts were not as important as the experimental group because their attitude towards the concepts was not changed. It appeared that it was important for parents to learn those concepts in Hong Kong.

Finally, the researcher would also like to see if the demographic distribution, opinion on effect of the television violence, and amount of media use would affect the results. There was a significant relationship between the participants’ perception of the workshop concepts and the amount of education they had received. According to the results from the multiple regression analysis, only educational background influenced their perception of the workshop concepts. The results suggested that how much education the participants had affected how they responded to the concepts. This might not be surprising. The more educated the participants were, the more receptive and open-minded they were to the concepts.

In short, the workshop of the “Taking Charge of Your TV” was well received in its first presentation in Hong Kong. The concepts of the workshop helped participants understand how to view television violence more critically and perhaps decrease the negative influence of television violence on their children in a long run. This very same workshop has been widely presented in the United States. The researcher believes that the intention of the workshop is good, and it should be promoted to educators and parents in Hong Kong for future research. If this workshop is broadly used in Hong Kong, parents will be perhaps more sensitive to the content on television, and researchers can continue to test the effectiveness of the workshop in Hong Kong and share the findings in the future.

Limitations

Scientific studies often face limitations, and this study is no exception.

The research was conducted in Hong Kong with the help from two organizations that mainly work with parents, the Happy Child Development Project and the Federation of Parent Teacher Associations. Thus the participants were not randomly selected from the general population. The researcher not being in Hong Kong was also a limitation Communication was extremely difficult, exacerbated by the lack of familiarity of the organizations with the study and the researcher. The only way for the researcher to recruit participants was to contact the organizations that would be interested in the study and ask them to recruit. It would be preferable to select the participants not only from the organizations that work with parents, but also to give everyone else an equal opportunity to be selected, resulting in a more representative sample.

In addition, there are potential problems in implementing the study. The data were collected through questionnaires with no additional interviews or means of identifying any discrepancies between reported and actual behavior.

Suggestions for Future Studies

The participants for this study were selected from two organizations that work mainly with parents. Participants from other groups should be selected randomly to make the groups more representative. A larger number of samples is always preferable in any study even though sample size is usually smaller in experimental studies compared to surveys.

Instead of relying on questionnaires, the researcher would like to invite the participants to write a journal or a diary to keep track of their television viewing behavior, and the frequency of implementing the concepts learned in the workshop at home. In addition, it would be desirable to interview the participants regarding their television viewing behavior.

In conclusion, the “Taking Charge of Your TV” workshop was first introduced in the United States in 1994 to focus on issues related to television and the influence of television violence. Learning the skills presented in the “Taking Charge of Your TV” could be helpful to parents and children to become more critical viewers when watching television. But learning the “Taking Charge of Your TV” workshop was not the only solution to the problems of violent content on television. Parents, educators, and researchers should work together to help our next generations to be smarter viewers. At the same time, researchers should continue to test the effectiveness of the workshop in the United States first. If it is proven to be effective, the workshop should be widely promoted in both the Western and Eastern nations.

References

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (2000). Attitudes and the attitude-behavior relations: reasoned and automatic processes. In W. Stroebe & M. Hewstone (Eds.), European Review of Social Psychology. Chichester, England: Wiley.

Brown, J.A. (2001). Media literacy and critical television viewing in education. In D. Singer & J. Singer (Eds.), Handbook of Children and the Media (pp. 681-698). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Buckley, R. (1997). Hong Kong: the Road to 1997. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bushman, B.J. & Huesmann, L. R. (2001). Effects of televised violence on aggression. In D. Singer & J. Singer (Eds.), Handbook of children and the media (pp. 223-254). Thousand Oaks. CA: Sage.

Chan, T., & Lee A. (2000). Managing TV with your kids. Hong Kong: Breakthrough, Ltd.

Davison, W. (1974). News Media and International Negotiation. Public Opinion Quarterly, 28, pp.174-191.

Donnerstein, E., Slaby, R.G., & Eron, L.D. (1994). The mass media and youth agression. In L.D. Eron, J.H. Genty, & P. Schlegel (Eds.), Reason to hope: A psychosocial perspective on violence and youth (pp. 219-250). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Flora, S., & Logan, R. (1996). Using computerized psychology examinations: An experimental analysis, Psychology Reports 79 (1): 235-241

Groebel, J. (2001). Media violence in cross-cultural perspective. In D. Singer & J. Singer (Eds.), Handbook of children and the media. Thousand Oaks. CA: Sage.

Hobbs, R. (1998). Media literacy in Massachusetts. In A. Hart (Ed.), Teaching the media: International perspectives (pp. 127-144). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Hong Kong Annual Report (2000). Hong Kong: Hong Kong Government Publications.Hong Kong Annual Digest of Statistics 2000 (2000). Hong Kong: Hong Kong Government Publications.

Huston, A. C. , Donnerstein, E., Fairchild, H., Feshback, N.D., Katz, P.A. , Murray, J.P., Rubinstein, E.A., Wilcox, B.L., & Zuckerman, D. (1992). Big world, small screen: The role of television in American society. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Hutcheon, S. (1998). Pressing Concerns: Hong Kong’s Media in an Era of Transition. Cambridge: Harvard University. De-Westernizing Media Studies. New York: Routledge.

Josephson, W.L. (1987). Television violence and children’s aggression: Testing the priming, social script, and disinhibition predictions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 882-890.

Johnson, M.M. (2001). The Impact of Television and Directions for Controlling What Children View. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, Fall 2001.

Lamson, S.R. (1995). Media violence has increased the murder rate. In C. Wekesser (Ed.), Violence in the media (pp. 25-27). San Diego, CA: Greenhaven Press.

National PTA. (2001). National PTA: Taking charge of your TV. Retrieved September 20, 2001, from http://www.pta.org

National PTA. (2004). National PTA: Taking charge of your TV. Retrieved October 30, 2005, from http://www.pta.org

Ma, K.W. (1999). Culture, Politics, and Television in Hong Kong, New York: Routledge.

Mok, E. (2000, March 28). Learn to keep a critical eye on television. South China Morning Post, p.C6.

Newman, D., & Rabushka, A. (1998). Hong Kong Under Chinese Rule the First Year. Stanford: Stanford University.

Rogers, F. (2001). A point of view: Family Communication, Television, and Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. Journal of Family Communication. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Shih, M.H. (1999). Testing a Critical Viewing Skills Project “Taking Charge of Your TV” in Taiwan. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale.

Singer, J.L., & Singer, D. G. (1983). Implications of childhood television viewing for cognition, imagination, and emotion. In J. Bryant & D. R. Anderson (Eds).

Children’s understanding of television (pp. 265-295). New York: Academic Press. Singer, J.L., & Singer, D. G. (1990). The house of make-believe. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Stone, G., Singletary, M., & Richmond, V. (1999). Clarifying Communication Theories. Ames: Iowa State University Press.

Tangney, J.P., & Feshbach, S. (1988). Children’s television viewing frequency: Individual differences and demographic correlates. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 14, 145-158.

The Hong Kong Journalists Association (2005). Annual Report. Retrieved December, 2005, from http://www.hkja.org.hk/press_free/index.htm

Thurstone, L.L. (1931). The measurement of social attitudes. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 26, 249-269.

Triandis, H. C. (1971). Attitude and attitude change. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Van Evra, J. V. (1998). Television and Child Development. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Watkins, L.T., Sprafkin, J., Gadow, K.D., & Sadetsky, I. (1988). Effects of a critical viewing skills curriculum on elementary school children’s knowledge and attitudes about television. Journal of Educational Research, 81, 165-170.Wilkins, K. Hong Kong Broadcasting. Retrieved June 8, 2002, from http://www.Museum.TV/archives/index.shtml

Wood, W. (2000). Attitude change: Persuasion and social influence. Annual Review Psychological. 51, 539-570.

Wong, R. (2000). Youth Trends in Hong Kong 2000. Hong Kong: Sunshine Press Ltd.

Yan, M. (2001, July). Revamping Hong Kong’s broadcasting policy. The Sixth Asia Pacific Regional Conference. Paper presented at the International Telecommunications Society Conference.