Blurring the Source: Information Laundering and the Cognitive Architecture of Modern Propaganda

Douglas S. Wilbur

Independent Researcher

Abstract

Contemporary propaganda often succeeds not by inventing falsehoods, but by obscuring where information comes from. This study examines how state-aligned messaging weakens source visibility as narratives circulate across digital media environments. Analyzing 200 Kremlin-aligned texts archived by EUvsDisinfo, we combine automated language analysis with close qualitative review to identify recurring patterns that blur attribution. The findings show that vague references to authority, recycled phrasing, and repeated re-use of claims across outlets systematically erode audiences’ ability to track authorship, even when the content itself remains familiar. To explain this process, the study introduces the concept of attribution decay: the gradual loss of source cues produced by repetition, intertextual borrowing, and cross-platform circulation. Rather than treating source confusion as a cognitive failure alone, the analysis shows how contemporary media infrastructures actively facilitate this erosion. By linking research on memory and source monitoring with the study of mediated discourse and propaganda, the article demonstrates how networked communication environments allow disinformation narratives to persist and gain credibility long after their original sources have faded from view.

Key Words: source confusion, misinformation, propaganda, attribution, cognitive bias, information laundering

Douglas S Wilbur, Ph.D. (University of Missouri, School of Journalism, 2019), is a strategic communication scientist who specializes in propaganda, information warfare, strategic communication, psychological operation and others. He is a retired US Army Information Operations Officer with 4 combat deployments. Douglas is currently an independent researcher who works in the IT industry. Douglas_wilbur@yahoo.com

Introduction

In mediated communication environments, the circulation of discourse across multiple outlets and platforms can transform not only what is said, but how authorship and accountability are perceived. Contemporary propaganda rarely relies on overt falsehoods; instead, it manipulates the linguistic markers that connect statements to their sources. As claims are echoed, reframed, and recycled across news portals and blogs, attribution becomes diffuse—a process that blurs the line between citation, quotation, and invention. This study explores how such mediated revoicing practices reshape the visibility of provenance in discourse. Specifically, it examines how repeated exposure, vague authority references, and intertextual borrowing contribute to the erosion of source cues within a networked media ecology. By systematically analyzing these discursive features, the paper introduces attribution decay as a new theoretical concept for understanding how mediation itself produces conditions of source confusion.

Decades of psychological research have demonstrated that people often recall information without remembering its origin. Most of this literature has been confined to controlled laboratory settings using artificial stimuli such as word lists, headlines, or photographs (Johnson, 1997). These studies establish the basic mechanisms of source confusion, but they leave unanswered the question of how the phenomenon is intentionally engineered in real-world propaganda. Propaganda and misinformation scholarship has begun to identify practices consistent with this exploitation. Particularly through information laundering, a process by which extremist or false narratives are introduced through disreputable venues and gradually re-circulated through increasingly mainstream channels until their dubious origin is obscured (Klein, 2012). Cursory reviews of literature suggest that Russian information warfare exemplifies this approach. They have systematically amplified stories through a chain of blogs, state outlets, and sympathetic foreign media (Starbird et al., 2019). Yet these accounts remain largely descriptive, and no study has systematically measured the rhetorical or structural features of propaganda texts that make them especially prone to laundering and source confusion. This gap leaves analysts without empirical tools to identify when propaganda is deliberately crafted to exploit source-monitoring vulnerabilities, despite growing evidence that such tactics are becoming more common.

Addressing this gap is significant because it advances the ecological validity of research on misinformation and memory. Much of the experimental literature has relied on decontextualized stimuli, such as single headlines, word lists, or manipulated photographs, to isolate source-monitoring effects (Kemp, Loaiza, Kelley, & Wahlheim, 2024). While valuable, such designs do not capture the rhetorical complexity of propaganda, which often layers vague attribution, borrowed authority, and repetition into longer-form texts. By applying content analysis to authentic propaganda articles, this study situates source confusion in the environments where it naturally occurs. As Ecker, Lewandowsky, and Cook (2015) argue, research must move beyond artificial tasks to inform real-world interventions against misinformation. Examining how propagandists craft messages that are designed to survive attribution decay not only enriches theory but also provides analysts with empirically grounded indicators for detecting when narratives are engineered to outlive their sources.

The purpose of this study is to examine how state-backed propaganda texts are constructed to facilitate source confusion. Using original Russian propaganda texts, identified through the EUvsDisinfo database, we conduct a systematic content analysis to identify rhetorical and structural features. By situating source confusion within the strategic practice of information laundering (Klein, 2012), this study bridges experimental research on memory with applied analyses of mediated communication and disinformation dynamics. In doing so, it contributes both to theory, by extending source-monitoring frameworks into authentic propaganda contexts, and to practice, by offering analysts empirically grounded indicators for recognizing when disinformation is designed to outlive its source.

Review of Literature

Psychological Foundations

Source confusion is not just a simple memory error. It reflects how people process and store familiar or emotionally charged information. Source monitoring theory explains that misattributions occur when perceptual details, contextual cues, or emotional tone are too weak or too similar to distinguish one memory from another (Mitchell & Johnson, 2000). When this happens, people rely on quick judgments based on plausibility or emotional fit rather than recalling the true origin. Studies show that the effect becomes stronger when information is repeated, feels believable, or aligns with existing beliefs (Lentoor, 2023). Memory for facts tends to hold, but memory for where those facts came from often fades. This imbalance helps explain why misinformation spreads easily. The details remain vivid while the source slips away, a pattern first described in foundational research by Johnson, Hashtroudi, and Lindsay (1993).

Research on source confusion has identified a range of factors that make misattribution more likely. One of the most consistent findings is that imprecise attribution, such as recalling that “experts say” without naming the source, weakens source memory and increases reliance on heuristics (Mitchell & Johnson, 2000). Similarly, studies show that borrowing authority from prestigious figures or institutions, even when those sources are only vaguely referenced, can lend content credibility while making the original provenance harder to trace (Lind, Visentini, Mäntylä, & Del Missier, 2017). Research on eyewitness suggestibility further demonstrates that vague or ambiguous wording reduces the likelihood that individuals will later remember the exact source of a detail (Deffenbacher, Bornstein, & Penrod, 2006). Related work in discourse processing suggests that when a speaker’s editorial voice is blurred with quoted material, audiences often misremember the statement as a direct fact rather than an attributed claim (Lyle & Johnson, 2007). Finally, repetition across contexts is a powerful amplifier. Repeated claims feel more familiar, are recalled with greater confidence, and are increasingly likely to be remembered without their original source (Brown & Marsh, 2008). Together, this body of work demonstrates that attribution precision, appeals to authority, vagueness, voice blurring, and repetition are empirically validated drivers of source confusion.

Power of Repetition and Framing

Repetition is a steady driver of source confusion. It makes information feel familiar and fluent, but it does little to strengthen memory for where the information came from. When people encounter a claim several times, they grow more confident in the content but less certain about its origin. This pattern is known as the illusory truth effect (Brown & Marsh, 2008). The problem deepens when multiple outlets repeat similar claims. The echoes create a false sense of corroboration. Studies of social contagion in memory show that people often absorb details introduced by others into their own recollections, blurring the line between firsthand and secondary knowledge (Roediger, Meade & Bergman, 2001). Collective remembering produces the same result. As groups recall events together, they tend to align their memories and lose track of provenance (Greeley & Rajaram, 2023). Each repetition weakens the link between content and source, setting the stage for propaganda to merge messages across outlets and build the illusion of shared truth.

A further set of factors linked to source confusion involves the ways information is framed and attributed in discourse. Research on memory conformity shows that vague or generalized phrasing, such as attributing claims to “people say” or “experts believe,” undermines the specificity of source memory and increases the risk of misattribution (Gabbert, Memon, & Wright, 2006). Similarly, experimental work on rumor transmission demonstrates that when messages are retold, details of attribution are among the first elements to be dropped. This leads recipients to recall the content but not its origin (Allport & Postman, 2005). More recent studies highlight how appeals to authority and social endorsement can amplify this process. Individuals are more likely to accept and later misremember information when it is framed as coming from prestigious sources or endorsed by others in their network (Pornpitakpan, 2004). These findings suggest that vague attribution, the natural erosion of source details in retelling, and the persuasive power of authority cues all interact to create conditions in which source confusion is not incidental but predictable (Metzger, Flanagin, & Medders, 2010). This underscores why the study of misinformation and propaganda must account for how such cues are strategically embedded in messages to ensure that content survives even as provenance fades.

Source Confusion in Misinformation and Propaganda

Misinformation is commonly defined as “false or misleading information that is communicated regardless of intent to deceive” (Lewandowsky, Ecker, & Cook, 2017, p. 353). A growing body of research demonstrates that exposure to misinformation in news-like formats can create false memories and durable beliefs. For example, Schincariol, O’Mahony, and Greene’s (2024) meta-analysis found that approximately one in five participants later recalled fabricated news events as real, highlighting the fragility of source monitoring in ecologically valid contexts. Brown and Marsh (2008) similarly showed that prior exposure to unfamiliar items led participants to misremember them as autobiographical experiences, illustrating how fluency cues can override accurate source recall. Lentoor (2023) further argues that the neural mechanisms underlying these distortions involve failures to bind contextual and perceptual details, leaving individuals with strong memory for content but weak memory for origin. These findings underscore that news-like misinformation exploits predictable cognitive weaknesses in source monitoring, making false memories a critical entry point for understanding propaganda’s persuasive impact.

Repetition is a powerful driver of misinformation’s influence because repeated claims feel more familiar and therefore more credible, even when false. This illusory truth effect has been documented across multiple contexts. Fazio, Brashier, Payne, and Marsh (2015) showed that repetition increased perceived truth of statements regardless of prior knowledge, while Pennycook, Cannon, and Rand (2018) demonstrated that even a single prior exposure to fake news headlines significantly boosted their perceived accuracy. Corrective efforts can mitigate these effects, but their success depends on the extent of recollection. Swire-Thompson, DeGutis, and Lazer (2020) found that corrections reduced belief in false claims, yet repetition still enhanced familiarity, leaving individuals vulnerable when corrections were forgotten. Together, these findings highlight how repetition accelerates attribution decay, strengthening memory for content while weakening memory for origin, and why corrective strategies must account for this asymmetry.

While source confusion describes the cognitive misattribution of origin (Johnson, Hashtroudi, & Lindsay, 1993), its persistence in real communication environments suggests that an additional process helps misinformation endure beyond initial exposure. Research on the continued influence effect shows that even after correction, people often continue to rely on false information in reasoning and recall (Lewandowsky, Ecker, Seifert, Schwarz, & Cook, 2012). Likewise, repetition and familiarity bias increase the feeling that a claim is true while doing little to reinforce memory for its source (Fazio, Brashier, Payne, & Marsh, 2015). These findings point to a deeper mechanism: as messages are repeated, echoed, and reframed across multiple outlets, the cues linking content to origin gradually weaken. To capture this process, the present study introduces the concept of attribution decay: The progressive weakening of source cues through repetition and cross-source fusion, enabling information to circulate and appear credible even as its origin becomes obscured. Rather than describing a cognitive phenomenon directly, attribution decay refers to a communicative pattern visible in textual and cross-platform analysis, one that plausibly contributes to audience misattribution over time.

The type of claim also shapes how misinformation is remembered and attributed. Research shows that opinions are often more closely tied to their sources than factual statements, because subjective content is encoded with richer contextual and affective cues. For instance, Ranganath and Nosek (2008) found that evaluative statements elicited stronger source memory than neutral facts, suggesting that affective valence enhances attribution. Similarly, Bayen, Nakamura, Dupuis, and Yang (2000) demonstrated that factual statements are more prone to source monitoring errors than evaluative or belief-based content. In the context of misinformation, Ecker, Lewandowsky, and Apai (2011) showed that people are more likely to misremember the source of factual corrections compared to opinions, a vulnerability that allows misleading factual claims to circulate detached from their origins. These findings indicate that the nature of the claim, fact versus opinion, systematically influences attribution precision. Propaganda exploits this asymmetry by embedding authoritative “facts” more than contestable opinions.

Authority cues and social endorsements further magnify misinformation’s impact by encouraging acceptance while weakening memory for the original source. Classic persuasion research shows that high-credibility sources increase belief strength even when their role is not explicitly remembered (Hovland & Weiss, 1951/2005). More recent work demonstrates that social validation serves as a heuristic, in which endorsements from peers or influencers enhance perceived accuracy without strengthening source attribution (Colliander, 2019). In online contexts, Metzger, Flanagin, and Medders (2010) find that users often rely on simple heuristics, such as popularity cues, likes, or authority labels, to evaluate credibility, thereby increasing the risk of misattribution. Together, these studies illustrate that appeals to authority and social proof create conditions where propaganda can “borrow” credibility, gaining persuasive traction even as the memory of its true source erodes.

Misinformation rarely circulates in isolation; its impact grows through narrative amplification and cross-source fusion, where repeated appearances across platforms create the illusion of independent confirmation. Research on disinformation networks shows that coordinated co-sharing between mainstream and fringe outlets blurs boundaries of origin, lending false narratives a veneer of legitimacy (Guess, Nyhan, & Reifler, 2018). Goel, Anderson, Hofman, and Watts (2016) similarly demonstrate how social media diffusion enables fringe claims to achieve mainstream visibility via a cascade of intermediaries. These studies underscore that propaganda does not merely rely on individual cognitive vulnerabilities but strategically engineers attribution decay and cross-source fusion to exploit them (Guarino et al., 2020; Pierri et al., 2022). What remains underexplored, however, is systematic evidence from propaganda texts themselves, where these mechanisms are deliberately embedded as rhetorical strategies.

Research Questions

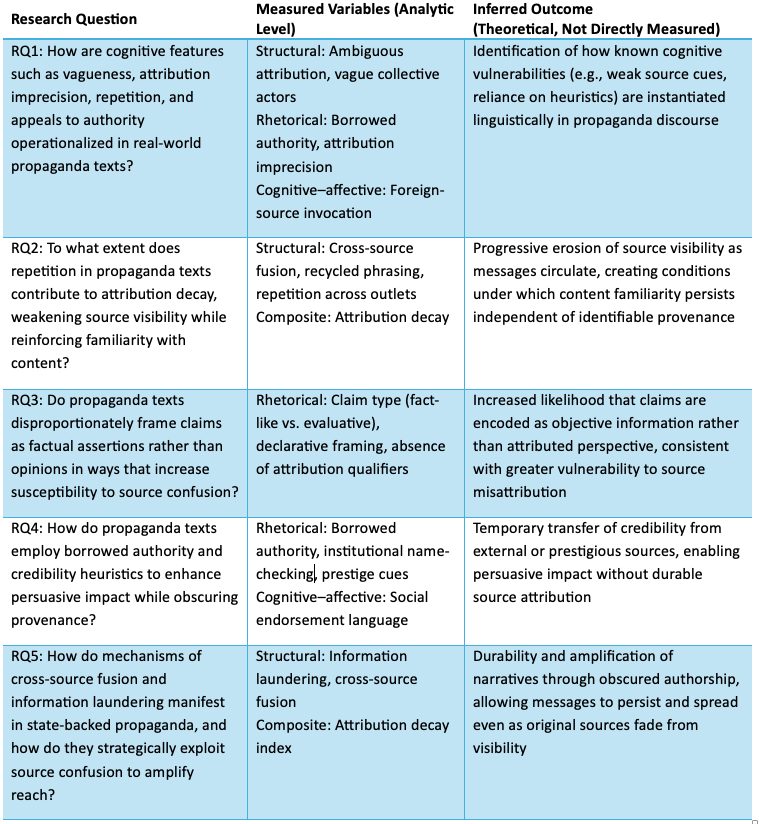

The preceding literature demonstrates that source confusion is not simply an individual cognitive error but a predictable outcome of repeated exposure, vague attribution, borrowed authority, emotional framing, and cross-platform circulation. Research in cognitive psychology shows that repetition and fluency strengthen memory for content while weakening memory for provenance, while scholarship on misinformation and propaganda documents how these vulnerabilities are strategically exploited through information laundering and narrative amplification. Despite these advances, prior work has rarely examined how such mechanisms are instantiated within authentic propaganda texts themselves, nor how specific rhetorical and structural features contribute to attribution decay in real-world media environments. Motivated by this gap, the present study examines how state-aligned propaganda texts are constructed to weaken the visibility of the source while sustaining persuasive impact. Rather than directly measuring audience cognition, the analysis focuses on textual indicators that prior research has shown to plausibly activate source-monitoring vulnerabilities. Accordingly, the study poses the following research questions as presented in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Research Questions

Methods

This study employed a mixed-methods content analysis integrating quantitative NLP-based coding with qualitative interpretive review. The design combined automated pattern detection with manual verification to capture both the measurable frequency and the rhetorical nuance of cognitive cues linked to source confusion. Analysis focused on three major variable groups: structural indicators (e.g., information laundering, cross-source fusion, attribution decay, ambiguous attributions) that obscure or blur the origin of claims; rhetorical frames (e.g., victimhood, proxy-war, delegitimization, and moral equivalence) that lend ideological justification; and cognitive–affective features (e.g., emotional tone toward the West and foreign-source invocation) that shape perception and recall. This mixed design allowed quantitative comparison across a large corpus while retaining the interpretive depth needed to trace how propaganda operationalizes memory-based biases in real-world discourse.

Sample

The study drew its dataset from the EUvsDisinfo database, a project established by the European External Action Service’s East StratCom Task Force. EUvsDisinfo systematically archives, translates, and annotates examples of pro-Kremlin disinformation appearing in multiple languages across traditional and digital media. Each entry in the database links to the original article or broadcast and includes short analyst notes summarizing the false or misleading claims. Because these materials originate from verified state-aligned outlets such as RT, Sputnik, and affiliated regional portals, the archive provides a credible and consistently curated source of propaganda texts suitable for systematic study. Using EUvsDisinfo ensures both authenticity (state-linked messaging) and comparability (uniform collection standards and temporal coverage).

A purposive sampling approach was employed to isolate materials most relevant to the study’s theoretical focus on source confusion. From the full database, articles were selected if they (a) contained identifiable textual narratives rather than video transcripts or social-media fragments. (b) addressed geopolitical themes involving the European Union, NATO, Ukraine, or the United States, (c) exhibited rhetorical framing or attributional structures that could be meaningfully coded. This method aligns with typical qualitative content-analytic logic, prioritizing conceptual richness and analytical depth over population representativeness. The final corpus comprised (N=200) articles published between 2022 and 2025. This sample size balances breadth and manageability: it is large enough to support descriptive and correlational statistics while allowing detailed manual verification of automated codes. Prior methodological research in computational propaganda analysis indicates that 150–250 documents generally provide sufficient variance to identify dominant rhetorical patterns and stabilize frequency estimates (e.g., Barberá et al., 2021; Wilson & Starbird, 2020). The resulting dataset, therefore, offers both analytic reliability and interpretive depth, appropriate for a mixed-methods design.

Data Analysis

To avoid conceptual ambiguity, it is important to clarify that the three categories used in this study—structural, rhetorical, and cognitive–affective—function as analytical groupings rather than measured variables in their own right. Each grouping contains discrete, theoretically derived indicators that were individually operationalized, coded, and analyzed. Structural indicators (information laundering, cross-source fusion, and ambiguous attribution) capture textual mechanisms that obscure or diffuse authorship and were primarily used to evaluate research questions on attribution decay and source erosion (RQ1, RQ2, RQ5). Rhetorical indicators (delegitimization, victimhood, proxy-war framing, and moral equivalence) capture narrative strategies that shape interpretive context and were used to assess how ideological framing covaries with attributional ambiguity (RQ2, RQ3). Cognitive–affective indicators (foreign-source invocation and emotional tone toward the West) capture affective and heuristic cues known to influence source monitoring and were used to evaluate the relationship between emotional framing, borrowed authority, and source confusion (RQ1, RQ4). Variables were therefore measured at the indicator level, with groupings used solely to organize related mechanisms and clarify their theoretical function within the overall analytic design.

For clarity, the Results section is organized by research question and draws on specific indicators accordingly. RQ1 is evaluated using structural indicators of attributional ambiguity alongside cognitive–affective cues of emotional tone and foreign-source invocation. RQ2 is assessed using repetition-linked structural indicators, particularly cross-source fusion and information laundering. RQ3 focuses on rhetorical framing indicators that distinguish factual assertions from opinion-based claims, while RQ4 centers on borrowed authority cues captured through foreign-source invocation and emotional–moral framing. RQ5 draws on the full set of structural indicators to examine coordinated attributional shifts associated with information laundering and cross-source fusion.

Analytical Strategy

The analytical strategy balanced computational precision with qualitative interpretive depth, recognizing that source confusion functions both as a measurable textual pattern and a rhetorical phenomenon shaped by context. Prior studies of misinformation have shown that automated language models can identify recurring lexical and structural markers of bias but may misclassify ordinary vagueness as intentional manipulation (Rashkin et al., 2017). Conversely, purely qualitative analysis provides contextual nuance but lacks scalability for pattern detection across large corpora (Kermani, 2023). To address these limitations, the study adopted a hybrid analytic design that combined natural language processing (NLP) techniques with manual interpretive coding, following approaches used in recent computational discourse research (Guetterman, Fetters & Creswell, 2015). This integration made it possible to quantify linguistic cues linked to cognitive bias while preserving the interpretive judgment required to distinguish strategic ambiguity from conventional stylistic variation

All propaganda texts were processed through a Python-based NLP pipeline that extracted and quantified key structural, rhetorical, and cognitive–affective variables (Rashkin et.al., 2017). The variables were derived through a deductive process that linked theoretical constructs from cognitive psychology, rhetoric, and disinformation research to observable textual indicators. The structural group captured mechanisms associated with information laundering, cross-source fusion, and ambiguous attribution, features theorized to blur perceived source reliability and increase susceptibility to misinformation (Lewandowsky, Ecker, Seifert, Schwarz, & Cook, 2012). These patterns reflect the circulation dynamics that allow content to appear independent while retaining coordinated origin. The rhetorical group was informed by studies of propaganda framing, particularly research identifying delegitimization victimhood, proxy-war narratives, and moral equivalence as recurring persuasive forms in state-aligned discourse (Miskimmon, O’Loughlin, & Roselle, 2013). Finally, the cognitive–affective group measured features associated with emotional resonance and attributional signaling, including foreign-source invocation and emotional tone toward the West, following prior findings that affective polarity and perceived external validation amplify message credibility (Vosoughi, Roy, & Aral, 2018).

To maintain interpretive rigor, the automated results were evaluated through an iterative constant comparison process. Coders reviewed each article’s NLP-derived output to verify that linguistic indicators genuinely represented intentional source ambiguity rather than incidental phrasing. During this stage, sentence-level context and paragraph structure were examined to determine whether vague or shifting attributions functioned rhetorically, such as laundering authority or merging conflicting narratives, or reflected routine journalistic convention. Explicit and verifiable attributions were recoded as “absent” to prevent inflation of prevalence scores. This comparative approach followed the constant comparison method outlined by Charmaz (2014), in which emerging patterns are continually tested against prior cases to refine interpretive consistency. In doing so, the study adhered to Neuendorf’s (2017) recommendation that reliability and validity in mixed-method content analysis depend on sustained cross-case calibration rather than single-pass coding.

Quantitatively, scores were scaled from 0 (absent) to 2 (strong) and averaged to produce article-level intensity values. To ensure conservative interpretation, thresholds were tightened post hoc: ≥ 1.5 indicated strong source confusion, 1.0–1.49 moderate, and < 1.0 absent. Descriptive statistics and cross-tabulations were used to explore relationships between confusion intensity and rhetorical frames. Reliability testing on a 15% subsample yielded Krippendorff’s α = .81, supporting consistency across coding rounds. After recalibration, 21% of texts exhibited strong evidence of source confusion, 35.5% moderate, and 43.5% none, suggesting that the tactic is strategically selective rather than universal in Kremlin-aligned media.

Findings

Overall, the analysis revealed that source confusion is a recurring but selectively deployed strategy within Russian-aligned propaganda. Approximately 56% of analyzed texts displayed moderate-to-strong indicators of attributional obfuscation. The remaining 44% maintained transparent sourcing and were classified as absent. This pattern suggests that, rather than a universal feature of Kremlin messaging, source confusion functions as a targeted rhetorical tool, most often activated when the message aims to legitimize contested narratives, externalize blame, or fuse Russian claims with Western credibility cues. The mixture of explicit sourcing and deliberate ambiguity reflects a sophisticated balancing act: retaining a veneer of journalistic authenticity while subtly eroding the audience’s ability to remember where information originated. The findings illustrate how cognitive vulnerabilities like source misattribution, repetition effects, and belief persistence are operationalized in rhetorical structure. Texts exhibiting higher source confusion intensity consistently employed complex attribution chains. For instance, vague collective subjects (“Western experts,” “analysts say”), and circular references linking Western institutions back to Russian frames. These patterns align with the concept of information laundering. Conversely, articles classified as “absent” typically relied on single-source attribution and contained verifiable quotations. This suggests that the manipulation of provenance is a strategically chosen, not incidental, feature of Kremlin communication.

Research Questions

Research Question 1: How are cognitive features such as vagueness, attribution imprecision, repetition, and appeals to authority operationalized in real-world propaganda texts?

Quantitative results show that source confusion was present at moderate levels across the text corpus. A one-sample t-test indicated that the mean source confusion intensity (M = 1.09, SD = 0.62) was significantly greater than zero, t(199) = 21.37, p < .001, 95% CI [1.00, 1.18], confirming that attributional ambiguity occurred well above baseline levels. A supplementary Wilcoxon signed-rank test corroborated this finding, Z = −11.84, p < .001. Among individual indicators, cross-source fusion (M = 1.21, SD = 0.71) and ambiguous attribution (M = 1.15, SD = 0.68) were the most frequent, while information laundering (M = 0.83, SD = 0.54) was less common. The overall effect size (d = 1.51) suggests that while not ubiquitous, source confusion is a systematic rhetorical feature rather than an incidental stylistic artifact.

This pattern is illustrated by statements that attribute claims to vague or unnamed authorities, such as the assertion that “according to experts in the field of international security, the collective West does not even conceal its interest in controlling the raw material and industrial potential of Central Asia under the guise of partnership” (Sputnik News, 2024, November 23). The reference to indeterminate “experts” fuses external authority with official Russian viewpoints. This lends the appearance of analytic consensus while concealing the claim’s true origin. The absence of verifiable attribution encourages readers to conflate external validation with official Russian messaging. Precisely the form of source confusion described in source-monitoring theory (Johnson, Hashtroudi, & Lindsay, 1993). Taken together, these findings indicate that while nearly half the analyzed texts presented clear, traceable sourcing, the remainder relied on deliberate ambiguity and blended authority structures to manipulate audience perception. Source confusion thus emerges not as a universal hallmark of Russian propaganda but as a selectively deployed cognitive strategy used to reinforce claims requiring borrowed credibility or plausible deniability.

Research Question 2: To what extent does repetition in propaganda texts contribute to attribution decay, weakening memory for source while reinforcing memory for content?

Statistical analysis revealed that delegitimization and proxy-war frames were most strongly associated with higher source confusion intensity scores. A one-way ANOVA comparing mean confusion scores across major frame types showed a significant effect of rhetorical framing on the degree of source confusion, F(3, 196) = 9.42, p < .001, η² = .13. Post hoc Tukey tests indicated that texts emphasizing delegitimization (M = 1.34, SD = 0.59) and proxy-war narratives (M = 1.28, SD = 0.65) contained significantly higher confusion levels than those emphasizing victimhood (M = 0.92, SD= 0.54) or moral equivalence (M = 0.88, SD = 0.57). These results suggest that when propaganda seeks to challenge the legitimacy of Western institutions or to portray ongoing conflicts as Western-engineered, it relies more heavily on attributional ambiguity and blended authority to strengthen plausibility.

This pattern is exemplified by the claim that “Europe is being turned into the Fourth Reich, with Brussels dictating policies that strip nations of their sovereignty while pretending to uphold democratic values” (Russia Today, 2024 May 2). Here, the text fuses historical analogy with political accusation, invoking the moral resonance of fascism without offering any concrete evidence or identifiable sources. The reference to “Brussels” functions as both a geographic marker and a moral antagonist, collapsing institutional critique into an emotional indictment of Western hypocrisy. This conflation of evaluative and factual language exemplifies how delegitimization frames amplify source confusion. They substitute moral certainty for empirical verification, blurring the line between analysis and accusation. Taken together, these findings indicate that the most rhetorically charged narratives also exhibit the greatest degree of attributional distortion, reinforcing the strategic link between ideological framing and cognitive manipulation.

Research Question 3: Do propaganda texts disproportionately frame claims as factual assertions rather than opinions to maximize susceptibility to source confusion?

Statistical results showed that information laundering was a distinct but moderately frequent mechanism within the dataset. Mean scores for information laundering (M = 0.83, SD = 0.54) were lower than those for ambiguous attribution and cross-source fusion but exhibited strong positive correlations with both variables, r(198) = .61, p < .001 and r(198) = .58, p < .001, respectively. These relationships indicate that laundering rarely appears in isolation. It often operates as part of a multi-layered rhetorical process in which attribution decay and external validation reinforce one another. Texts exhibiting higher laundering scores were significantly more likely to invoke Western or institutional authority without direct citation, t(198) = 8.42, p < .001, suggesting that credibility transfer from Western sources is a recurring structural tactic rather than an incidental linguistic feature.

This relationship is exemplified by a 2024 article claiming that “according to analysts cited by leading European energy media, the fullness of Europe’s gas reserves is actually a sign of weakness that makes the continent more dependent on external suppliers” (Russia Today, 2024 October 18). The statement presents itself as an informed summary of Western analysis, yet the absence of identifiable publication names or authors renders its sourcing unverifiable. Through this process of information laundering, a narrative originating from Russian state media is reframed as European expert commentary, effectively obscuring its provenance while amplifying its perceived legitimacy. This rhetorical transposition mirrors the laundering dynamics described by Phillips (2021), in which disinformation acquires new authority as it circulates through intermediaries and reemerges under the guise of neutral expertise. In the current corpus, laundering serves as both a mechanism of credibility enhancement and a trigger for cognitive misattribution, leading audiences to recall the information while forgetting its propagandistic origin. This is a hallmark of source confusion.

Research Question 4: How do propaganda texts employ borrowed authority and credibility heuristics to enhance persuasive impact while obscuring provenance?

Quantitative analysis demonstrated that emotional and moral appeals were strongly correlated with higher source confusion intensity scores across the corpus. Articles coded as high in moral-emotional language, particularly themes of Western hypocrisy and showed significantly greater attributional ambiguity than neutral-toned texts, t(198) = 6.47, p < .001, d = 0.91. A Pearson correlation confirmed this association, revealing that emotional tone toward the West was positively related to source confusion intensity, r(198) = .64, p < .001. These findings suggest that emotionally charged discourse amplifies the conditions under which audiences are more likely to misattribute the origin of information. A result consistent with prior cognitive research on affective bias and memory distortion (Storbeck & Clore, 2008).

A striking illustration appears in a 2024 RIA Novosti article asserting that “Russophobia has become the main criterion for joining the European Union, and those who fail to display sufficient hostility toward Moscow are treated as traitors to European values” (RIA Novosti, 2024). The language fuses emotional accusation with moral judgment, constructing a binary moral order in which hostility toward Russia becomes equated with virtue. The piece provides no evidence of EU policy or official statement supporting this claim. The invocation of “European values” serves as an unverified moral referent, transforming a political assertion into a moral indictment. The absence of verifiable sourcing, combined with affect-laden framing, encourages readers to internalize the judgment while forgetting its unverifiable origin. A process congruent with source-monitoring theory (Johnson, Hashtroudi, & Lindsay, 1993). This blending of moral certainty and attributional opacity exemplifies how emotional framing not only strengthens propaganda’s persuasive appeal but also deepens the cognitive confusion surrounding where the message originated.

Research Question 5: How do mechanisms of cross-source fusion and information laundering manifest in state-backed propaganda, and how do they strategically exploit source confusion to amplify reach?

Quantitative results indicated that roughly 44 percent of the analyzed articles scored below the presence threshold (< 1.0) for Source Confusion Intensity, signifying clear or traceable attribution. A comparison of absent versus present cases revealed a significant difference in attribution clarity, t(198) = 13.25, p < .001, d = 1.87. This confirms that a substantial subset of Kremlin-aligned content adheres to conventional sourcing practices. The majority of these low-scoring texts were short, fact-based dispatches that quoted official statements or covered diplomatic events without interpretive commentary. Correlation analysis further showed a negative relationship between emotional tone and source confusion (r(198) = −.58, p < .001), indicating that texts with neutral or bureaucratic style tended to maintain attributional transparency. These results suggest that propaganda outlets alternate between modes of communication, factual reporting that builds credibility, and rhetorical distortion that strategically deploys ambiguity.

An illustrative example appears in a 2024 TASS report noting that “the Azerbaijani Foreign Ministry issued a statement condemning the actions of the EU, NATO, and the United States, accusing them of double standards in regional affairs” (TASS, 2024). Unlike the emotionally charged or vaguely sourced pieces examined earlier, this report identifies the speaker (the Azerbaijani Foreign Ministry), specifies the content (a public statement), and provides a direct quotation from an official source. The structure mirrors conventional news writing, with clear attribution and minimal evaluative framing. The transparency of sourcing limits the risk of source confusion because readers can easily trace information to its origin. Such examples confirm that Russian state media does not operate under a single propagandistic mode but instead oscillates between credible reportage and strategic obfuscation, reinforcing the notion that source confusion is a selectively activated rhetorical technique designed to enhance the credibility of more controversial narratives.

Discussion

The findings of this study demonstrate that source confusion is neither a peripheral accident of propaganda nor a universal trait of Russian-aligned media. Rather, it is a strategically selective rhetorical technique. Quantitative results revealed a moderate overall presence across the corpus, with confusion most pronounced in delegitimization and proxy-war narratives and least apparent in factual diplomatic reports. This pattern indicates that attributional ambiguity functions as a contextual tool. Activated when the message requires borrowed authority or emotional amplification. Qualitative evidence reinforces this interpretation. Vague attributions such as “experts say” or “Western analysts believe” repeatedly fused Western credibility with Kremlin narratives, while neutral pieces quoting official statements maintained transparent sourcing. The alternation between clarity and obfuscation suggests a dual communication strategy, one that uses credible reportage to sustain perceived reliability and calculated ambiguity to shape audience belief when persuasion demands it.

At a broader level, the results extend psychological models of source monitoring into the domain of strategic communication. The consistent co-occurrence of emotional and moral framing with attributional decay underscores that affective content and cognitive confusion are mutually reinforcing rather than independent variables. Propaganda messages that evoke anger, threat, or moral indignation also produce the strongest erosion of source memory, heightening receptivity to disinformation. Conversely, emotionally neutral or clearly sourced texts restore attributional boundaries. Implying that cognitive manipulation in propaganda operates on a continuum of intentional design rather than a binary of truth versus falsehood. These dynamics reveal that modern propaganda does not simply transmit misleading information; it engineers the conditions of memory and belief. It exploits the same biases documented in experimental psychology to produce durable, self-validating impressions of credibility.

Theoretical Implications

The findings extend source-monitoring theory by showing how mechanisms observed in laboratory settings manifest in mediated communication. Johnson, Hashtroudi, and Lindsay (1993) describe source confusion as arising when contextual cues are too weak to support accurate attribution. Practices amplify familiarity while obscuring provenance, reproducing at scale the key condition for false memory formation, the separation of content recognition from source identification. This study also builds on Phillips’s (2021) theory of information laundering, reframing it as a structural process that sustains source confusion. Laundering does not simply cleanse reputational risk. It disperses authorship so thoroughly that origin becomes unrecoverable. Within this ecology, disinformation functions less as a series of discrete falsehoods and more as a recurring informational texture that feels credible through repetition. Source confusion, therefore, operates not merely as a cognitive error but as a deliberate communicative design, one that links rhetorical strategy to the predictable biases of human memory.

Practical Implications

These findings hold practical value for communication strategy, media literacy, and diplomacy. Recognizing that source confusion is deliberately employed underscores the limits of verification systems focused only on factual accuracy. Fact-checkers and analysts should also assess source integrity, the presence of citations, identifiable actors, and traceable cross-references, as their absence can indicate strategic obfuscation. Media literacy programs should train audiences to notice when information feels familiar yet lacks a clear source. Exercises that trace claims through their chain of attribution can rebuild awareness of how repetition and echoing obscure authorship. The same understanding can help diplomats and communicators interpret inconsistencies in authoritarian messaging as deliberate rhetorical devices rather than errors. Ultimately, these results suggest a shift from chasing falsehoods to detecting engineered ambiguity. Strengthening awareness of how repetition erodes source cues offers one of the most effective defenses against propaganda that relies less on deception than on fading memory of who is speaking.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that source confusion has evolved into a deliberate and systematic instrument of modern propaganda. This research revealed that attributional ambiguity is not a random artifact but a calibrated rhetorical device, strategically deployed to blur authorship, distribute responsibility, and heighten emotional resonance. The findings show that propagandists exploit the same cognitive shortcuts that underlie everyday memory. They weaponize familiarity and moral framing to produce narratives that feel true even when their origins dissolve into uncertainty. In doing so, they transform an individual cognitive bias into a collective epistemic condition: a world in which the line between information and its source no longer anchors belief. The paper’s contribution lies not only in documenting this phenomenon but in connecting two previously separate literatures—source-monitoring theory in psychology and information laundering in strategic communication—to reveal a shared logic of manipulation. By showing how disinformation architectures mimic the mind’s own vulnerabilities, the study reframes propaganda as a cognitive technology. One that manages attention, memory, and emotion as efficiently as it manipulates facts. This integration offers scholars a new framework for analyzing disinformation beyond truth-value assessments, while providing practitioners and policymakers with concrete diagnostic tools for identifying engineered ambiguity in real-world narratives.

Ultimately, this study extends mediated discourse analysis by demonstrating how the circulation and revoicing of texts across platforms reshape the linguistic visibility of source attribution. By theorizing this process as attribution decay, it shows that mediation itself, not only message content, functions as a discursive force that transforms how authorship, credibility, and meaning are constructed in contemporary communication.

Funding and Conflict of Interest Statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The author declares that no financial, institutional, or personal relationships influenced the design, execution, or reporting of this study. All analyses and interpretations are the author’s own and were conducted independently without external sponsorship or editorial involvement.

References

Allport, G. W., & Postman, L. (2005). The psychology of rumor (Rev. ed.). Russell & Russell. (Original work published 1947)

Andrade, C. (2018). Internal, external, and ecological validity in research design, conduct, and evaluation. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 40(5), 498–499. https://doi.org/10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_334_18.

Barberá, P., Boydstun, A. E., Linn, S., McMahon, R., & Nagler, J. (2021). Automated text classification of news articles: A practical guide. Political Analysis, 29(1), 19–42. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2020.8

Bayen, U. J., Nakamura, G. V., Dupuis, S. E., & Yang, C. L. (2000). The use of schematic knowledge about sources in source monitoring. Memory & Cognition, 28(3), 480–500. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03198562

Beach, D., & Pedersen, R. B. (2019). Process-Tracing Methods: Foundations and Guidelines (2nd ed.). University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.10072208

Brown, A. S., & Marsh, E. J. (2008). Evoking false beliefs about autobiographical experience. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 15(1), 186–190. https://doi.org/10.3758/PBR.15.1.186

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). London, UK: SAGE Publications.

Colliander, J. (2019). “This is fake news”: Investigating the role of conformity to other users’ views when commenting on and spreading disinformation in social media. Computers in Human Behavior, 97, 202–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.03.032

Deffenbacher, K. A., Bornstein, B. H., & Penrod, S. D. (2006). Mugshot exposure effects: Retroactive interference, mugshot commitment, source confusion, and unconscious transference. Law and Human Behavior, 30(3), 287–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10979-006-9008-1

Ecker, U., Lewandowsky, S., & Apai, J. (2011). Terrorists brought down the plane!-No, actually it was a technical fault: Processing corrections of emotive information. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 64, 283-310. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2010.497927

Ecker, U. K. H., Lewandowsky, S., & Cook, J. (2015). Beyond misinformation: Understanding and coping with the “post-truth” era. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 6(4), 353–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2017.07.008

Entman, R. M. (2008). Theorizing mediated public diplomacy: The U.S. case. International Journal of Press/Politics, 13(2), 87–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161208314657

Fazio, L. K., Brashier, N. M., Payne, B. K., & Marsh, E. J. (2015). Knowledge does not protect against illusory truth. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 144(5), 993–1002. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000098

Gabbert, F., Memon, A., & Wright, D. B. (2006). Memory conformity: Disentangling the steps toward influence during a discussion. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 13(3), 480–485. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193873

Goel, S., Anderson, A., Hofman, J., & Watts, D. J. (2016). The structural virality of online diffusion. Management Science, 62(1), 180–196. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2015.2158

Guetterman, T. C., Fetters, M. D., & Creswell, J. W. (2015). Integrating quantitative and qualitative results in health science mixed methods research through joint displays. Annals of Family Medicine, 13(6), 554–561. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1865

Greeley, G. D., & Rajaram, S. (2023). Collective memory: Collaborative recall synchronizes what and how people remember. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 14(4). https://doi.org/10.1002/wcs.1641

Guarino, S., Trino, N., Celestini, A., Chessa, A., & Riotta, G. (2020). Characterizing networks of propaganda on Twitter: A case study. arXiv Preprint arXiv:2005.10004. https://arxiv.org/abs/2005.10004

Guess, A., Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2018). Selective exposure to misinformation: Evidence from the consumption of fake news during the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign. European Research Council Working Paper. Retrieved from https://about.fb.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/fake-news-2016.pdf

Hovland, C. I., & Weiss, W. (2005). The influence of source credibility on communication effectiveness. Public Opinion Quarterly, 15(4), 635–650. (Original work published 1951) https://doi.org/10.1086/266350

Johnson, M. K., Hashtroudi, S., & Lindsay, D. S. (1993). Source monitoring. Psychological Bulletin, 114(1), 3–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.114.1.3

Johnson, M. K. (1997). Source monitoring and memory distortion. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 352(1362), 1733–1745. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1997.0156

Kemp, P. L., Loaiza, V. M., Kelley, C. M., & Wahlheim, C. N. (2024). Correcting fake news headlines after repeated exposure: Memory and belief accuracy in younger and older adults. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 9, Article 55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-024-00585-3

Kermani, H. (2023). Computational vs. qualitative: analyzing different features of online commentary in news media.Frontiers in Communication, 8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC11166045/

Klein, A. (2012), Slipping Racism into the Mainstream: A Theory of Information Laundering. Commun Theor, 22: 427-448. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2012.01415.x

Lentoor, A. G. (2023). Cognitive and neural mechanisms underlying false memories: Misinformation, distortion or erroneous configuration? AIMS Neuroscience, 10(3), 255–268. https://doi.org/10.3934/Neuroscience.2023020

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., & Cook, J. (2017). Beyond Misinformation: Understanding and Coping with the “Post-Truth” Era. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 6 (4), 353-369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2017.07.008

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., Seifert, C. M., Schwarz, N., & Cook, J. (2012). Misinformation and its correction: Continued influence and successful debiasing. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13(3), 106–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612451018

Lind, M., Visentini, M., Mäntylä, T., & Del Missier, F. (2017). Choice-supportive misremembering: A new taxonomy and review. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2062. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02062

Lyle, K. B., & Johnson, M. K. (2007). Source misattributions may increase the accuracy of source judgments. Memory & Cognition, 35(5), 1024–1033. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193475

Metzger, M. J., Flanagin, A. J., & Medders, R. B. (2010). Social and heuristic approaches to credibility evaluation online. Journal of Communication, 60(3), 413–439. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2010.01488.x

Miskimmon, A., O’Loughlin, B., & Roselle, L. (2013). Strategic narratives: Communication power and the new world order. Routledge.

Mitchell, K. J., & Johnson, M. K. (2000). Source monitoring: Attributing mental experiences. In E. Tulving & F. I. M. Craik (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of memory (pp. 179–195). Oxford University Press.

Neuendorf, K. A. (2017). The content analysis guidebook (2nd ed.). Sage.

Phillips, W. (2021). Slipping racism into the mainstream: A theory of information laundering. Social Media + Society, 7(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120984457

Pierri, F., Luceri, L., Jindal, S., & Ferrara, E. (2022). Propaganda and misinformation on Facebook and Twitter during the Russian invasion of Ukraine. arXiv Preprint arXiv:2212.00419. https://arxiv.org/abs/2212.00419

Pennycook, G., Cannon, T. D., & Rand, D. G. (2018). Prior exposure increases perceived accuracy of fake news. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 147(12), 1865–1880. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000465

Pornpitakpan, C. (2004). The persuasiveness of source credibility: A critical review of five decades’ evidence. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34(2), 243–281. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb02547.x

RIA Novosti. (2024, September 12). Zakharova: The criterion for joining the European Union is now Russophobia.Retrieved from https://ria.ru/20240912/zakharova-russophobia-eu-1117050198.html

Rashkin, H., Choi, E., Jang, J. Y., Volkova, S., & Choi, Y. (2017). Truth of varying shades: Analyzing language in fake news and political fact-checking. Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (pp. 2931–2937). Association for Computational Linguistics. https://aclanthology.org/D17-1317.pdf

Ranganath, K. A., & Nosek, B. A. (2008). Implicit attitude generalization occurs immediately; explicit attitude generalization takes time. Psychological Science, 19(3), 249–254. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02076.x

Russia Today. (2024, May 2). Europe is being turned into the Fourth Reich. Retrieved from https://sputnikglobe.com/20240502/europe-is-being-turned-into-the-fourth-reich-1116123456.html

- (2024, October 18). Why are Europe’s full gas reserves a “sign of weakness” and vulnerability?Retrieved from https://sputnikglobe.com/20241018/why-are-europes-full-gas-reserves-a-sign-of-weakness-and-vulnerability-1117302012.html

Roediger, H. L., Meade, M. L., & Bergman, E. T. (2001). Social contagion of memory. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 8(2), 365–371. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03196174

Schincariol, A., O’Mahony, C., & Greene, C. M. (2024). Fake memories: A meta-analysis on the effect of fake news on the creation of false memories and false beliefs. Memory, 32(7), 938–951. 10.1017/mem.2024.14

Sputnik News. (2024, November 23). Destabilizing the Eurasian space is the West’s ultimate goal – Russian Foreign Ministry. Retrieved from https://sputnikglobe.com/20241123/destabilizing-the-eurasian-space-is-the-wests-ultimate-goal-russian-foreign-ministry-1117795482.html

Starbird, K., Arif, A., & Wilson, T. (2019). Disinformation as collaborative work: Surfacing the participatory nature of strategic information operations. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 3(CSCW), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1145/3359229

Storbeck, J., & Clore, G. L. (2011). Affect influences false memories at encoding: evidence from recognition data. Emotion (Washington, D.C.), 11(4), 981–989. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022754

Swire-Thompson, B., DeGutis, J., & Lazer, D. (2020). Searching for the backfire effect: Measurement and design considerations. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 9(3), 286–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2020.06.006

TASS. (2024, July 28). Azerbaijan’s Foreign Ministry makes a hurt statement against the EU, NATO, and the U.S.Retrieved from https://tass.com/politics/1997291

Tolstoj, K. (2023). Crucified Boy in Russian War Propaganda: How is Theology NOT Ideology? Handelingen: Tijdschrift voor Praktische Theologie en Religiewetenschap, 50(3), 29–37. https://doi.org/10.54195/handelingen.17999

Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146–1151. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap9559

Walther, J. B., DeAndrea, D., Kim, J., & Anthony, J. C. (2010). The influence of online comments on perceptions of antimarijuana public service announcements on YouTube. Human Communication Research, 36(4), 469–492. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2010.01384.x

Wilson, T., & Starbird, K. (2020). Cross-platform disinformation campaigns: Lessons learned and next steps. Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review, 1(1), 1–9. https://misinforeview.hks.harvard.edu/article/cross-platform-disinformation-campaigns/

Yablokov, I. (2015). Conspiracy theories as a Russian public diplomacy tool: The case of Russia Today (RT). Politics, 35(3–4), 301–315. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9256.12097

Zahavi, D. (2023). The unity and plurality of sharing. Philosophical Psychology, 38(5), 2003–2023. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2023.2296596