Press and Curl: An Examination of Ebony Magazine Covers to Understand the Cultural-Historical Trends of Black Women’s Hair

Tamekia-terin Smith

Howard University

Afiya Mbilishaka, PhD

University of the District of Columbia

Kalen Kennedy

Howard University

This research study examined the sociocultural standards of physical appearance presented to Black women through magazine covers from 1960-2009. The highest grossing African American print media publication to date, Ebony has become digitized with free online retrieval, giving access to a range of historical images of feminine beauty, with an emphasis on Black hair. Trends were investigated through a content analysis of Black female cover models (N=558) hair texture and length. Although a range of hairstyles was depicted on the magazine covers, straightened and curled hair remained the most frequent hair texture across all five decades and there was an increase in length from ear length hair in the 1960s to shoulder length hair in the 1990s. Both the consistency in hair straightening and an increase of hair length suggest that hair straightening is presented as a cultural-historical ideal for Black women. This trend parallels unhealthy hair altering practices, social comparison challenges, and political climate of American society.

Tamekia-terin Smith is a proud alumna of Howard University where she received her Bachelor of Science in Psychology minoring in Afro-American Studies.While at Howard University she participated largely as a researcher in the “psychohairapy” research laboratory, a practice centered around the utilization of hair as an entry point for mental health services. Tamekia-terin was born and raised in Long Beach, CA, and currently resides in the Chicago area where she works within Residence Life at the National Louis University.

Dr. Afiya Mbilishaka is a therapist, as well as an Assistant Professor of Psychology and researcher at the University of the District of Columbia that focuses on understanding and using traditional African cultural rituals for contemporary holistic mental health practices. She is a native New Yorker and graduated from the University of Pennsylvania and Howard University, where she studied the psychological significance of race within lives and earned a Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology. Dr. Mbilishaka also has an emerging program of practice and research entitled, “psychohairapy,” where she uses hair as an entry point for mental health services in beauty salons and barbershops, as well as through social media. She is the current Association of Black Psychologist DC chapter vice president.

Dr. Afiya Mbilishaka is a therapist, as well as an Assistant Professor of Psychology and researcher at the University of the District of Columbia that focuses on understanding and using traditional African cultural rituals for contemporary holistic mental health practices. She is a native New Yorker and graduated from the University of Pennsylvania and Howard University, where she studied the psychological significance of race within lives and earned a Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology. Dr. Mbilishaka also has an emerging program of practice and research entitled, “psychohairapy,” where she uses hair as an entry point for mental health services in beauty salons and barbershops, as well as through social media. She is the current Association of Black Psychologist DC chapter vice president.

Kalen Kennedy is a senior psychology major, minoring in allied sciences, at Howard University. He will be transitioning to Kennedy Krieger Institute, employed as a research assistant in the Hunter Nelson Sturge-Weber Center. He intends to seek a PhD in clinical psychology and his research interests include mental health inequity, race, culture, and societal hierarchy.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Tamekia-terin Smith at tamekiaterin@aol.com

Introduction

The images in magazines have the power to advertise, define, and archive the sociocultural standards of appearance and the visual grammar of a culture (Foster-Davis, 2001; Foley-Sypeck, Gray & Ahrens, 2004; Rooks, 2006; Pompper & Koenig, 2004; Schnell, 2008). Visual images in magazines have been used in psychological research to primarily investigate the depiction of thinness ideals for women; much of this research suggests that White American women internalize messaging regarding body type ideals that negatively impact their self-worth (Nemeroff et al, 1994; Botta, 2003; Pompper & Koenig, 2004; Park, 2005; Tiggmann, 2003; Thomsen, 2002). However, there is a dearth of psychological studies that analyze the role of magazine images that extend beyond thinness to focus on a culturally relevant variable for Black American women. Hair should be included as a factor in examining self-image within the visual culture of media, as hair is meaningful in the unique identity development of Black women (see Lewis, 1999; Capodilupo, 2014; Ashley & Brown, 2015; Ellis-Hervey et al, 2016).

Hair has emerged as a psychological variable in a recent focus group and oral interview studies on Black female self-perception (Capodilupo, 2014; Capodilupo & Kim, 2014; Ashley & Brown, 2015). Within a psychological study on the role of hair in self-image, Capodilupo (2014) found that the majority of the 230 Black female participants identified long and straight hair as a personal and cultural ideal. The participants identified the media as a major source of perpetuating the long and straight hair ideal for Black women (Capodilupo, 2014). Black women have natural hair textures that vary from tightly coiled natural curls to shiny straight tresses, embodying the broad range of phenotype (Byrd & Tharps, 2014). However, Black women can engage in hair styling practices to manipulate the texture and length by utilizing extreme heat, toxic chemicals, and hair extensions made from animals or other human beings (Byrd & Tharps, 2014). The way in which a Black woman chooses to wear her hair has been shown to affect her self-esteem, employment opportunities, parent-child relationships, romantic relationships, or even friendships with other Black women (Ellis-Hervey et al, 2016; King & Niabaly, 2013; Lewis, 1999; Weathers, 1991). This magazine research would extend these findings about Black women and self-image.

Magazines have been a part of the cultural communication for Black people in the United States since 1827 when the first Freedman’s Journal was published (Rooks, 2006). Further, Ebony magazine, according to its publisher, John H. Johnson (1968), was the publication that reflected the most authentic depiction of the lived experience of Black America. The images on the magazine’s covers at times reflect and at other times shape the standard of beauty for Black women across decades. Ebony has become digitized with free online retrieval, providing access to a collection of historical images of feminine beauty from1960 to 2009.

Ebony remains the highest globally circulated publication for African-Americans to date (Ebony, 2016). Its historical context is deeply steeped in Black entertainment, politics, and most notably, Black beauty. According to the Editor-in-Chief:

“Ebony is the No. 1 source for an authoritative perspective on the Black community . . . the monthly magazine, now in its 71st year, reaches nearly 11-million readers. EBONY features the best thinkers, trendsetters, hottest celebrities and next-generation leaders. EBONY ignites conversation, promotes empowerment and celebrates aspiration. Available nationwide on newsstands and the iPad, EBONY is the heart, the soul and the pulse of Black America. It’s more than a magazine, it’s a movement.” (“About EBONY”, 2016, p. 1)

The popularity or wide African American female readership of the magazine indicated that the content resonated with millions of Black women and may also their connection to the visual images seen inside and on the cover of the magazine. The images presented on the cover of Ebony were said to have reflected Black life, but in doing so also established a standard by which Black life was to continue to abide by. Judy Foster Davis (2001) detailed the specific marketing strategies utilized by White-owned marketing agencies to access the Black market, such as tailoring advertisements to political and social events of the time periods. The use of these strategies demonstrates how Ebony magazine followed social trends in order to maintain a grasp on the Black community, particularly the Black consumer market.

Ebony has been a source of print media data for other studies to analyze hair care marketing, stereotype portrayal, breast cancer coverage, and information about depression (Clarke, 2010; Davis, 2001, Bailey, Woodard & Mastin, 2005; Hazell & Clarke, 2008;Walsh-Childers, Edwards & Grobmyer, 2012). Thompson-Brenner, Boisseau, and St. Paul (2013) most recently conducted a study on Ebony magazine covers, investigating the change in body image for African American women. A multiple-rater content analysis was carried out on 462 issues, and 539 cover images of women. Thompson-Brenner, Boisseau, and St. Paul found a curvilinear relationship between time and figure exposure. This current research study, however, will extend the research on sociocultural standards of physical appearance to include the culturally relevant visual variable of hair. The authors examined Ebony magazine digitized covers from 1960 to 2009 to address two questions:

- What were the top hair textures and lengths presented on Ebony magazine covers from 1960-2009?

- Did the top hair texture and length of cover models change across decades?

Methods

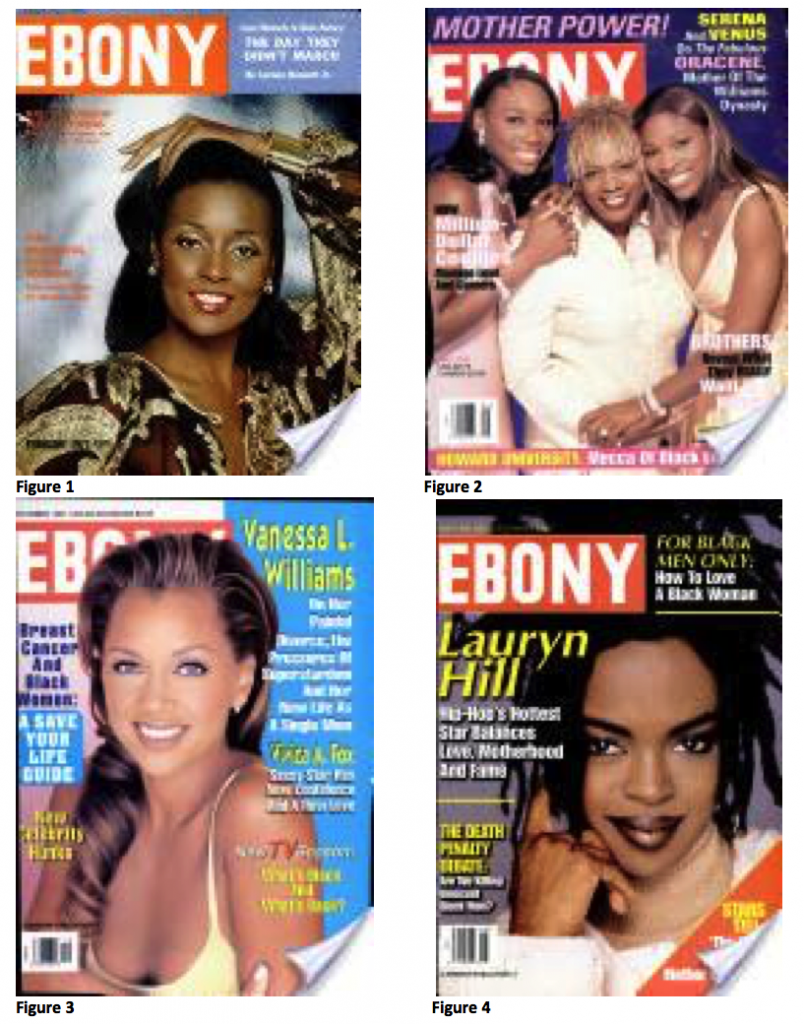

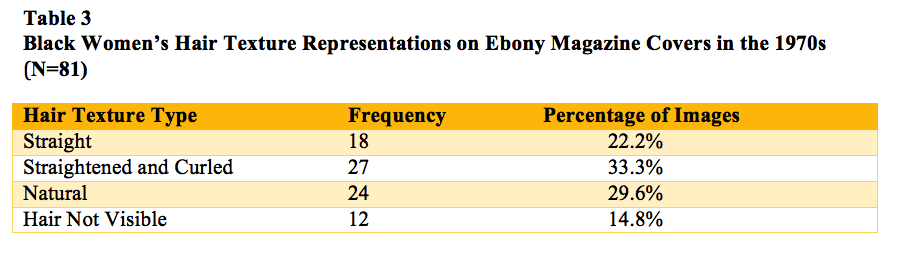

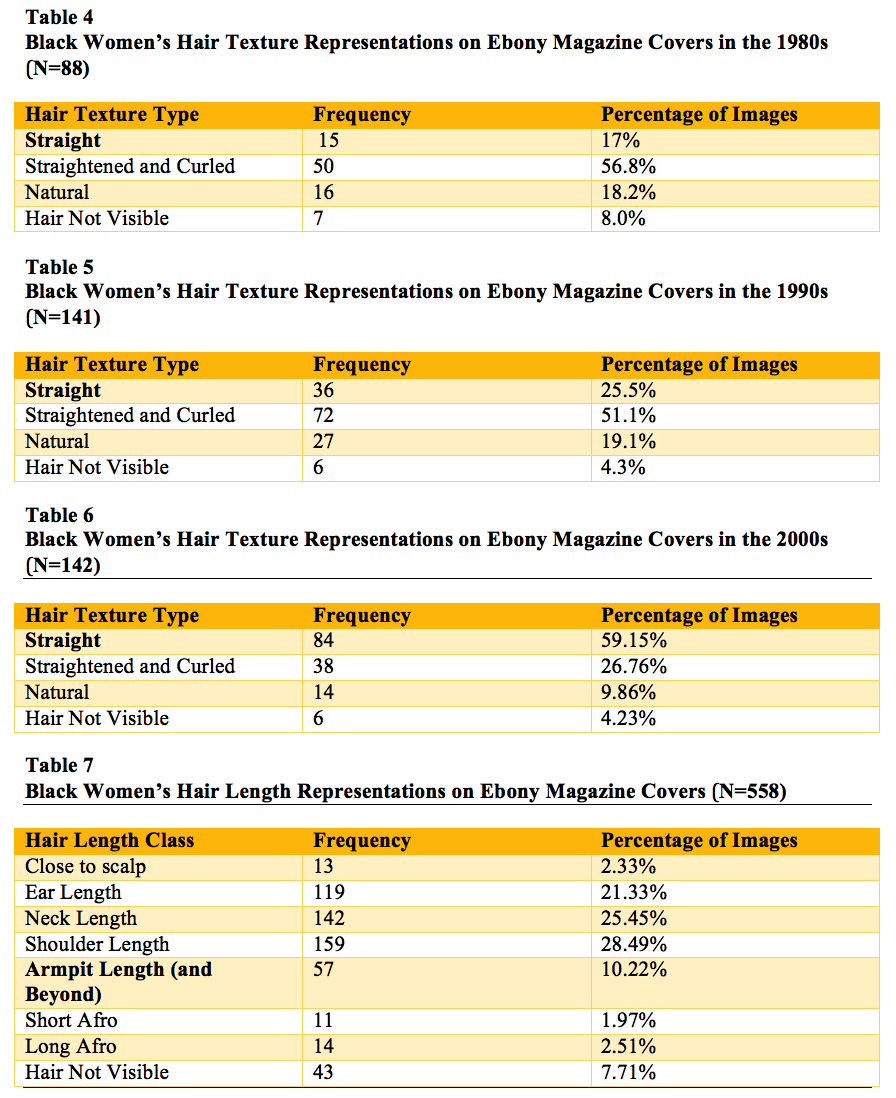

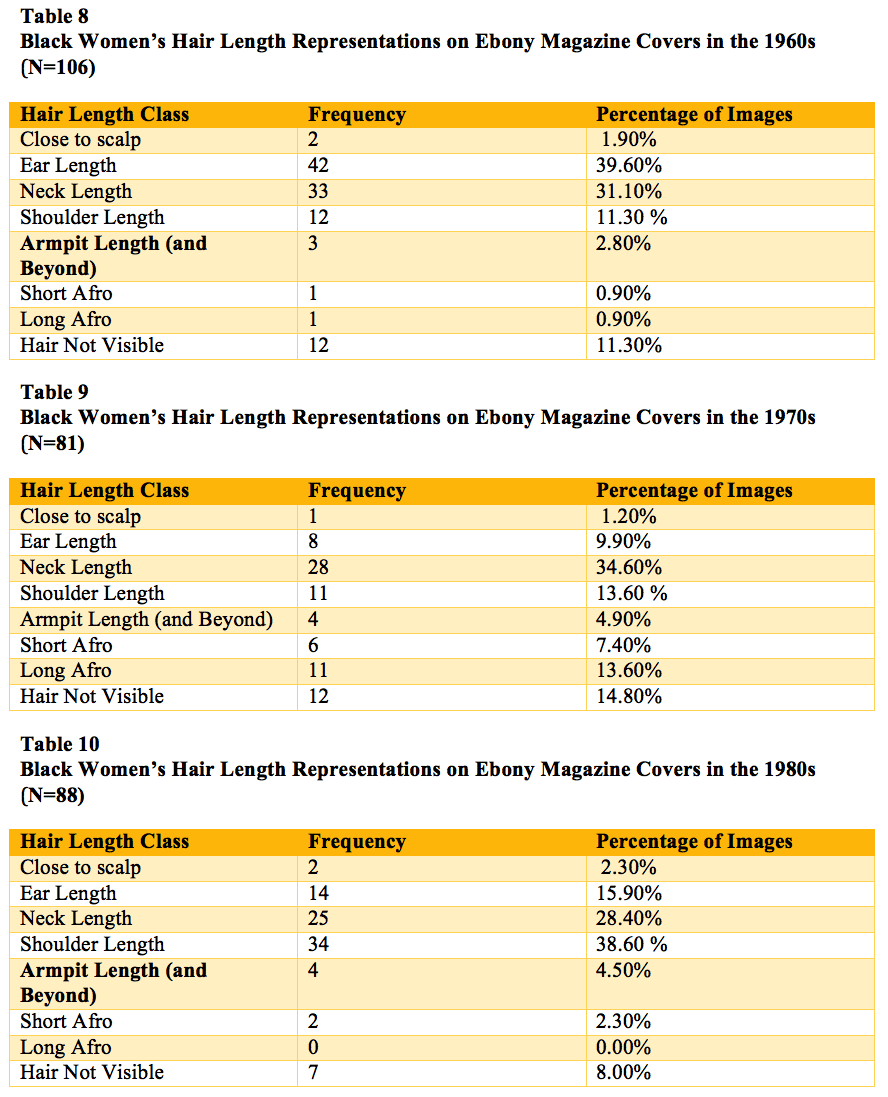

A group of 4-independent coders, with a minimum inter-rater reliability of .75, engaged in a content analysis of Ebony magazine covers for the years 1960-2009. The analysis involved complete decades from the beginning of the online Ebony archive, ending in the last complete decade made available through the archive. Only images of Black women were selected for analysis as these images have been shown to be most significant towards impacting perceptions of self for Black women (Festinger, 1954; Capodilupo, 2014). Images containing women of other races or women whose race could not be identified were not coded. In addition, covers that included a montage, solely men, non-hair related images, or hair that could not be clearly seen due to poor picture quality were not coded. Covers depicting multiple women (see figure 2) were analyzed beginning with the individual woman located in the center of the page, and evaluating clockwise until the hair texture and length of each woman was coded. Using the data coding scheme of Davis (2001) for hair textures in advertisements from Ebony, the data was coded using a coding system that placed hair texture into three categories, “straight”, (see figure 1) “straightened and curled,” (see figure 3) and “natural.” (see figure 4) “Straight” hair was defined as hair that appears to be smooth, lying flat against the scalp and reflecting light well, the direction of the hair shaft generally flows downward” (Davis, 2001, p. 36). Hair classified as “straightened and curled” has a visible loose curl pattern and is visibly straightened as well as styled with loose waves or curls. This hair texture may also reflect light but differs from straightened hair because of its volume, or visible curls. The “natural” hair category was defined as “hair that has a tight or loose curl, or coil, diffuses light with a hair shaft that seemingly grows outwards away from the scalp as opposed to lying flat on the scalp. (Davis, 2001). Natural hair may include afros, twists, locks, braids, and also hair that seem to be “neither straightened, nor curled, nor chemically, or thermally altered” (Davis, 2001, p. 36). The hair length included seven categories, “Close to scalp,” “ear length,” “neck length,” “shoulder length,” “armpit and beyond,” “short afro,” and “long afro.” A code of “hair not visible” was included in the categories of hair texture and length for hair that was fully covered by a hat, headwrap, or other head adornments. This code was also used to denote hair images that were unclear to researchers due to image quality. The image had to be completely visible to all researchers in order to receive a texture and length coding.

Results

After examining each of the 600 Ebony covers from January 1960 to December 2009, a total of 558 hair images were analyzed (n=558). The covers that were not coded either displayed men, montages (of more than 5 women), non-hair related images, or blurred figures. The most frequently represented hair texture across all decades for Black women was straightened and curled at 43.18% (241 observations, see Table 1). The straightened texture images were presented in 32.97% (184 observations) of the cover images and the natural hair texture group was presented at a frequency of 16.13% (90 observations). 7.71% of the hair images were not coded due to the hair not being visible (43 observations). In reference to length, the most frequently presented hair length was the shoulder length category, with 28.49% of the images (159 observations, see Table 2). This was followed by neck length and ear length hair with 25.45% (142 observations) and 21.33% (119 observations) of the images, respectively. Armpit length hair was presented in 10% of the images (57 observations). The least common hair lengths were close to the scalp, short afro, and long afro with frequencies of 2.33% (13 observations), 1.97% (11 observations), and 2.51% (14 observations), respectively.

Trends in the 1960s

Of the total 106 hair images coded, 79.9% of the hair was displayed in an altered state, with just over half of the hair trends consistent with the straightened and curled and category at 50.9% (see Table 3). Only 8.5% of the hair images were categorized as natural. The data collected suggested that the most frequently depicted hair length was ear length at 39.60%, followed by neck length hair images that were coded at 31.10%. The longer hair lengths were not very prevalent during the decade.

Trends in the 1970s

The number of hair images that depicted a natural hair texture more than tripled at 29.6% during the 1970s (see Table 4). This category included afros and free-flowing natural hair that has not been manipulated or styled. (i.e. braids, locs, twists, etc.) The most popular hair length was neck length hair category, representing 34.60% of the total hair images recorded. The trend demonstrates a higher frequency in presenting longer hair than that presented in the 1960s.

Trends in the 1980s

In the 1980s, a total of 88 hair images were coded with 56.8% (50 observations) of the hair images reflecting a straightened and curled hair texture. Only 18% of the hair images were of natural texture hair. 17.0% of the hair was coded as straightened resulting in more than 73% of the hair images reflecting straightened or altered hair textures. Another 28.40% of the hair images were representing neck length hairstyles. In this decade only 2 hair images were coded as afros, both categorized as short afros.

Trends in the 1990s

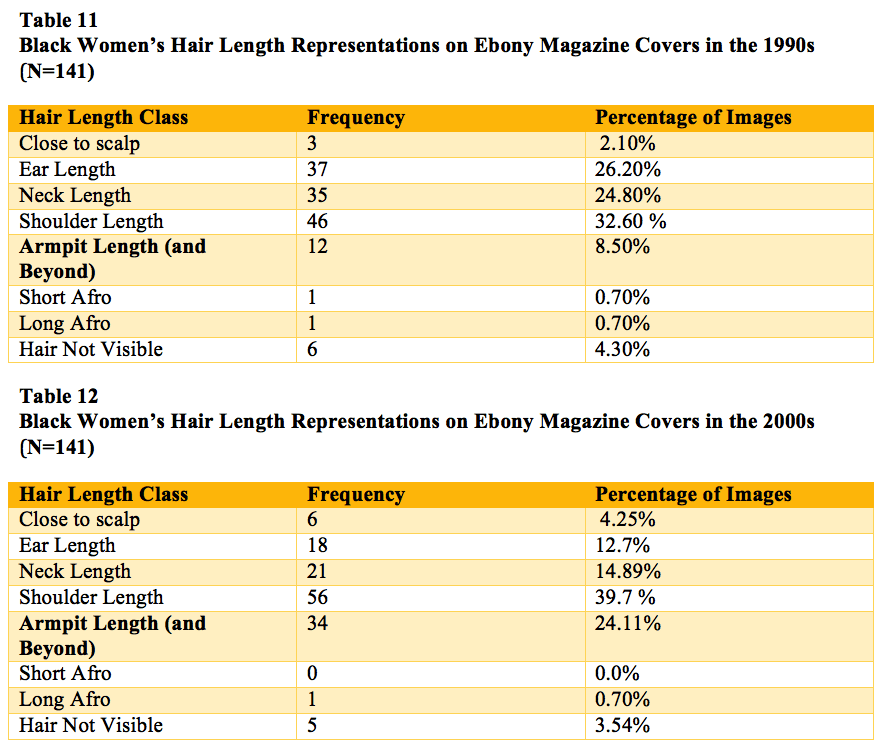

One hundred forty-one hair images were coded in the 1990s. Though hair images in the straightened category continued to rank as the most popular hair texture at 51.1%, the remainder of hair texture categories were represented in with straightened and curled hair accounting for 22.5% of the images, and natural texture accounting for 19.1% of the total images coded. For those hair images coded as depicting a natural hair texture, the distribution of hair images was almost equal across the two subclass categories of natural hair (natural state, and naturally styled). Researchers found that shoulder length category persisted as the most popular hair length at about 33% followed by ear length hair images at 26.2%, and neck length hair images at about 24.8%. 8.50% hair images coded in the armpit length and beyond category, creating a new trend for the decade.

Trends in the 2000s

A total of 141 hair images were coded in the 2000 decade. Continuing with the trend of previous decades, the straightened categories accounted for almost 86% of all the hair images coded within the decade (122 observations). However, researchers did see a change from the previous decade within the straightened category with over half of the images coded being coded as straight texture, at 59.15% (84 observations) displaying hair texture that was uncurled and clearly altered from its natural state. In previous decades straightened and curled categories were displayed at the highest frequencies. In measurements of length, shoulder length hair was recorded as the most frequent hair length at 39.7% (56 observations), followed by hair measured as armpit and beyond at 24.11% (34 observations).

Discussion

The presentation of hair textures and lengths in print media, specifically Ebony magazine, can serve as a historical timeline of appearance within the cultural-historical climate of the Black community. The results of this investigation create a foundation for researchers to further understand the role that visual media images play in shaping how Black women look from head to toe. Ebony, with over 11 million readers, not only provides trendy topics to their audience through the use of celebrities and models on their covers, but also implicitly extends public beliefs about how Black women do, and should wear their hair. The publication presents a narrative to and about Black women that was framed around long straightened and curled hair. One can assume that if Ebony magazine is lauded as “the most authentic reflection of the lived Black experience,” (Johnson, 1968) the images portrayed are accurate presentations and depictions of Black culture. This new assessment of media provides quantitative references to consider with Capodilupo’s (2014) findings that Black women identify long straight hair as a cultural beauty ideal. Capodilupo’s findings explored how the media affects Black women’s perception of beauty. The perpetual presentation of long, straight hair images can negatively impact the viewer’s evaluation of their own attractiveness.

Magazine covers present an image of Black women that when repeated over 50 years, although superficially innocuous, may have the power to archive and distribute cultural images about Black women as well as conserving perceptions of ideal hair texture and length across time. Further, this repetition may trigger the Mere-Exposure effect which posits that individual’s attitudes of stimuli are enhanced after repeated exposure (Zajonc, 1968). This theory holds that exposure to a certain image can be internalized and henceforth impact all future interpretations of similar stimuli. Therefore, exposure to a long, straightened hair beauty ideal could hold a lifetime of influence and desire to recreate the standard for Black women. Since not everyone can grow long straight hair, this may influence attractiveness dissatisfaction for some Black women.

The theory of social comparison is relevant to the interpretation of the findings from the current study, being that Black magazines are important data points for Black women making self-relevant meaning from like-others (Festinger, 1954). Inter-generationally, Ebony magazine has presented Black women with a variety of phenotypes. However, the majority of the presentations did not have hair lengths or textures that were common to the kinky and short natural texture of the average Black woman (Grier & Cobbs, 2000) This overrepresentation of straightened and curled hair could influence someone to think that close to the scalp natural hair is less attractive than longer, straightened hair. Furthermore, the work of Gunther and Storey (2003) would also imply that media has a large impact on self-image because of its presumed influence on the minds of others. Where all genders can be consumers of Ebony magazine, the realm of influence of these images of Black women’s hair to impact mate choice, status, and prosperity can be both real and imagined. Considering the role of genetic variation for Black women and their hair, the media may be perpetuating unrealistic, advertised norm that could have psychological implications. Not meeting a beauty standard may result in negative self-evaluation, as concluded in recent studies (Capodilupo, 2014, Capodilupo & Kim, 2014).

It is important to acknowledge that hair alteration practices may have a direct relationship with achieving these frequently portrayed beauty standards. When media impacts interpretations of attractiveness, Black women may engage in hair care practices to achieve a socially acceptable look. Hair altering practices over time can also lead to what Dr. Evelyn Winfield (2008) would call hair stress, which is defined as the physical and psychological stress related to altering one’s hair from its natural state. This study argues that hair stress is an important variable to consider when discussing the trends of Black hair on magazine covers, as it is often a result of Black women striving toward a standard set forth in the advertisements most visible to them. In acknowledging the role that media, specifically advertisement, plays in spending patterns, it would be remiss not to consider magazine covers as hair advertisements; these particular advertisements may influence Black women to spend money on obtaining long, straight hair (Rooks, 2006).

These results suggest that the highlighted hair care practices amongst Black women are heavily centered around hair styling practices commonly categorized as the “press and curl,” where hair is straightened from its natural state and then curled to add more volume and shape to the hair. These results cause researchers to ask the question, “Why is straightened and curled hair a cultural image norm for Black women?” It is possible that the ‘press and curl’ hairstyle is unique in that it can only be produced from a certain hair texture or length. Hair must be thermally straightened with a flat iron or straightening comb, then curled using a curling iron to achieve this style (Rooks, 1996). In other cases, hair is chemically processed to permanently remove the hair’s natural curl pattern, and later thermally straightened using an iron or straightening comb. Although this image could be interpreted as perpetuating a Eurocentric beauty standard, it has now also been incorporated into the history and culture of Black women’s hair. To achieve the cultural standard of beauty for long and straightened hair, Black women have developed an extensive weave culture, which may be represented in popular hair images (Byrd & Tharps, 2014). Traditionally, the straightened and curled hair texture was achieved through physical alterations to one’s actual hair. Magazine covers of the 1980s reflected the trend of hair extensions, which now allowed women to achieve the straightened and curled hair texture by simply adding hair extensions to their own hair.

In addition, the representation of the hair textures and lengths in print media, specifically Ebony magazine can serve as a historical timeline of the political climate of the Black community. Upon Ebony’s initial publication, John H. Johnson expressed an intended goal of capturing the mood of the Black middle class. Today, Ebony articles continue to address the issues most widely discussed in the Black community. Our findings point towards the socio-political meaning of hair shifting from “hairstyles” in the 1960s to “hair statements” in the 1970s considering that during this period, many individuals began to craft their hairstyles as a means of communicating their political views that rejected eurocentric dominant societal standards (Vibes, 2016).

Though the 1960s and 1970s were an extremely formative period for the construction of Black culture with the start Black power movement, the death of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., as well as the rise of the Black Panther Party (Byrd & Tharps, 2014; Banks, 2000; Leslie, 1995) , the hair images depicted on the cover of Ebony seem to capture the transition from the desire for political inclusion to the resistance of the mainstream American aesthetic as explained by Black Panther Party member Kathleen Cleaver in a 1968 interview (Vibes, 2016). In the 1960s-decade only 8.5% of the hair images on the cover of the publication were of natural hair textures, whereas close to 80% of the images displayed chemically and thermally straightened hair images and styles, or hair pieces including straightened wigs and hair extensions. This suggests that less than 1 in 10 Black women were represented with having natural hair texture. Though the socio-political tone of the Black community was outlined by a newfound “acceptance” and “celebration” of a “Black identified visual aesthetic” according to Byrd and Tharps consumers of Ebony magazine were consistently presented with an aesthetic that based on these results did not directly resemble their natural Black aesthetic (Byrd and Tharps, 2014).

During the 1970s, with the continuation of the Black Power movement, Black people began embracing their natural aesthetic, including their natural coiffures (Byrd and Tharp, 1995). Those hair images that were altered from their natural state texture type decreased from nearly 80% to about 55% of the total of hair images coded. This increase in natural hair texture depictions seems to be consistent with social and political changes during the decade (Leslie, 1995). This symmetry between one of the most authoritative sources of Black media and the social climate could easily increase the self-esteem of Black women since Black women were receiving visual and auditory confirmation of their natural beauty.

Our findings in the 1980s and 1990s represented an additional decline in natural hairstyles and an increase and straightened and curled hairstyles. In the 1980s, the aesthetic for Black beauty in media had begun shifting closely to that of the European aesthetic of longer, bigger, and straighter hair being categorized as most popular (Leslie, 1995). This shift can be explained by the publications deviation away from the socio-political culture and towards a more entertainment based culture. Images of individuals on the cover had veered away from national political and social figures, and heavily towards actors, singers, and stars of the time. A more glamorized and altered hair aesthetic was observed as hair trends shifted back towards longer straighter hair with 75% of the decade’s images displaying a straightened hair texture. Inconsistency with length trends over the decades, the popular hair length grew from ear length in the 60s, neck length in the 70s, and finally, shoulder length in the 80s, representing nearly 40% of the total hair images coded.

Most recently, the 1990s-decade of Ebony publications showed an increase of Black women’s media presence in areas such as politics, entertainment, business and even pageantry. Natural hair textures were present, however, the magazine continued to produce a more prominent visual narrative of straightened hair textures as dominant with 75% of the images displaying this category. Politics, celebrity status, and economic factors began impacting who was selected to be on the cover but did not have much impact on the variation of the hair texture and aesthetic Ebony magazine represented. Though the decade introduced a variety of different women on the cover of the magazine, the hair aesthetic remained unvaried with almost 60% of the images displaying straightened hair that fell below the shoulder. Throughout this decade the popular hair trends displayed on the cover of the magazines were not varied and continued to display a visual narrative of long, straight hair for Black women, although the Black female experience in America was quite diverse (Bell, 1990).

An analysis of the presentation of Black women’s hair on Ebony magazine covers over five decades suggests a bias towards one specific hair texture, as opposed to a representation of the varied textures worn by Black women. The hair texture and length of Black women vary widely from incredibly tight and glistening coils to long feathery waves. In America, several of these hair texture categories can be the defining factors in self-worth. Based on the results of this study, researchers can demonstrate the overrepresentation of long, straightened and curled hair across time in magazine images, and the implications they may have on the millions of Black women who subscribe to the magazine. Social scientists must continue to study hair images in magazines and how they affect the physical and mental health of its audience, as identification with various standards of beauty may have self-enhancing or stressful implications.

References

About EBONY. (2016, November). Retrieved March 23, 2017, from http://www.ebony.com/about-ebony#axzz4cApAYPB5

Ashley, W., & Brown, J. C. (2015). Attachment tHairapy: A culturally relevant treatment paradigm for African American foster youth. Attachment tHairapy: A culturally relevant treatment paradigm for African American foster youth,46(6), 587-604. doi:10.1177/0021934715590406

Banks, I. (2000). Hair matters: beauty, power, and black women’s consciousness. New York: New York University Press.Botta, R. A. (2003). For your health? The relationship between magazine reading and adolescents’ body image and eating disturbances. Sex Roles,48(9-10), 389-399. doi:10.1023/A:1023570326812

Bell, Ella Louise. “The bicultural life experience of career‐oriented black women.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 11, no. 6 (1990): 459-477.

Byrd, A., & Tharps, L. (2014). Hair story: Untangling the roots of Black hair in America. New York: Macmillan.

Capodilupo, C. M. (2014, August 25). One Size Does Not Fit All: Using Variables Other Than the Thin Ideal to Understand Black Women’s Body Image. Cultural

Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. Advance online publication. doi:10.1037/a0037649

Capodilupo, C. M., & Kim, S. (2014). Gender and race matter: The importance of considering intersections in Black women’s body image. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 61, 37–49.

Clarke, J. N. (2010). The portrayal of depression in the three most popular English- language Black-American magazines in the USA: Ebony, Essence, and Jet.

Ethnicity & Health, 15(5), 459-473.doi:10.1080/13557858.2010.488261

Ellis-Hervey, N., Doss, A., Davis, D., Nicks, R., & Araiza, P. (2016). African American Personal Presentation: Psychology of Hair and Self-Perception. Journal of Black Studies,47(8), 869-882. doi:10.1177/0021934716653350

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7, 117-140. doi:10.1177/001872675400700202

Foster Davis, J. (2001). “New Hair Freedom? 1990s Hair Care Marketing and the African-American Woman.” Conference on History Analysis and Research in Marketing, 31-41. Long Beach: Association for Historical Research in Marketing.

Giles, D. (2008). Media Framing Analysis. Media Psychology Review. Vol. 1(1)

Grier, W. H., & Cobbs, P. M. (1992). Basic Books (2nd ed.). Basic Books.

Gunther, A. C., & Storey, J. D. (2003). The influence of presumed influence. Journal of Communication, 53, 199–215. doi:10.1111/j. 1460-2466.2003.tb02586.x

Hazell, V., & Clarke, J. (2008). Race and Gender in the Media: A Content Analysis of Advertisements in Two Mainstream Black Magazines. Journal of Black Studies, 39(1), 5-21. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40282545

King, Vanessa and Niabaly, Dieynaba (2013) “The Politics of Black Womens’ Hair,” Journal of Undergraduate Research at Minnesota State University, Mankato: 13, 4. Available at: http://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/jur/vol13/iss1/4

Leslie, M. (1995). Slow Fade to?: Advertising in Ebony Magazine, 1957–1989. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly,72(2), 426-435. doi:10.1177/107769909507200214

Lewis, M. L. (1999). Hair combing interactions: A new paradigm for research with African-American mothers. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry,69(4), 504-514. doi:10.1037/h0080398

Nemeroff, C.J., Stein, R.I., Diehl, N.S., & Smilack, K.M. (1994). From the Cleavers to the Clintons: Role choices and body orientation as reflected in magazine article content. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 16, 167-176.

Park, S. (2005). The influence of presumed media influence on women’s desire to be thin. Communication Research, 32, 594-614.

Pompper, D., & Koenig, J. (2004). Cross-Cultural-Generational Perceptions of Ideal Body Image: Hispanic Women and Magazine Standards. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly,81(1), 89-107. doi:10.1177/107769900408100107

Rooks, N. M. (1996). Hair raising: Beauty, culture, and African American women. Rutgers University Press.

Rutledge, P. (2008) What is Media Psychology? A Qualitative Inquiry. Media Psychology Review. Vol. 1(1)

Rutledge, P. (2008) The Evolving Definition of Media Psychology. The Media Psychology Review. Vol. 7(2)

Schnell, J. (2008). Suggestions for Addressing the Increased Emphasis on Visual Imagery over Aural Messages. Media Psychology Review. Vol. 1(1)

Silva, K., & SIlva, F. (2014). Ages of Top Male and Female Money-Making Actors: 1932 to 2012. Media Psychology Review. Vol. 8(1)

Sypeck, M. F., Gray, J. J., & Ahrens, A. H. (2004). No longer just a pretty face: Fashion magazines’ depictions of ideal female beauty from 1959 to 1999. International Journal of Eating Disorders,36(3), 342-347. doi:10.1002/eat.20039

Thompson-Brenner, H., Boisseau, C. L., & Paul, M. S. (2011). Representation of ideal figure size in Ebony magazine: A content analysis. Body Image,8(4), 373-378. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.05.005

Thomsen, S. R. (2002). Health and beauty magazine reading and body shape concerns among a group of college women. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 79, 988-1007.

Tiggemann, M. (2003). Media exposure, body dissatisfaction and disordered eating: television and magazines are not the same! European Eating Disorders Review,11(5), 418-430. doi:10.1002/erv.502

Walsh-Childers, K., Edwards, H. M., & Grobmyer, S. (2012). Essence, Ebony & O: Breast Cancer Coverage in Black Magazines. Howard Journal Of Communications, 23(2), 136-156. doi:10.1080/10646175.2012.667722.

Weathers, N. (1991). Braided sculptures and smokin’ combs: African-American women’s hair-culture. Sage, 8(1), 58-61.

Winfield, E. (August 2008). “Hair Stress”: 40 Years with a Perm: Psychological and Physical Consequences of African American Women’s Hair Care Practices. Presented at the 40th Annual Convention of The Association of Black Psychologists,. Oakland, CA.

Woodard, J. B., & Mastin, T. (2005). Black Womanhood: Essence and its Treatment of Stereotypical Images of Black Women. Journal of Black Studies,36(2), 264-281. doi:10.1177/0021934704273152

Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of personality and social psychology, 9(2p2), 1.

Vibes, Zoe. (2016, September 4). Natural hair is beautiful (Kathleen cleaver). Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vkToPsh1Cos