Demystification of The Oprah Winfrey Effect

Michael Scott Garner, PhD

Fielding Graduate University

From a television consumption perspective, The Oprah Winfrey Show was not only a highly rated TV show, but it also shined a light on the host herself, casting her as both an emotionally relatable personality and a transformative figure, particularly with a female audience (Peck, 1994, 2015; Squire, 1994; Wilson, 2003). This qualitative study was executed to understand the production-side experience of The Oprah Winfrey Show’s impact on the audience and explore the idea of Oprah’s legacy (Garner, 2021) through interviews with five executives who work or worked for Oprah Winfrey during the production of The Oprah Winfrey Show syndicated series (1986-2011).

Keywords: Oprah Winfrey, qualitative research, transformation, audience impact

Michael Scott Garner, Ph.D. icott Garner is a senior programming and brand strategist, with 25 years of experience in content curation, marketing and research for leading Fortune 500 companies. Garner uses a data-driven approach to build competitive and strategic business plans that define, differentiate and accentuate a brands platform to successfully connect with consumers. He currently runs his own consulting firm, Conqueror Media, focused on helping both large and small clients navigate the rapidly evolving media and entertainment industry. Scott specializes in consumer insight and primary research, trend tracking, competitive landscape analysis, content library management, domestic and international program strategy and content acquisitions and management. Scott holds a Ph.D. in Media Psychology at Fielding University and a Master of Arts degree from Columbia University (New York City) michaelscottgarner@me.com.

Introduction

From a television consumption perspective, The Oprah Winfrey Show was not only a highly rated TV show, but it also shined a light on the host herself, casting her as both an emotionally relatable personality and a transformative figure, particularly with a female audience (Peck, 1994, 2015; Squire, 1994; Wilson, 2003). Pease and Brewer (2008) noted that Winfrey’s influence extended beyond products to consumers of the daily talk show as she discovered how to engage in earnest discussions with the studio and home audiences in a way that created meaning for them across numerous topics (Nurfazrina, 2016; Peck, 2010). Recent fan comments suggest that her personal effect was also meaningful for viewers and appears to remain so, despite the number of years since Oprah appeared on her daytime talk show. This effect indicates that her influence continues (Renfro, 2020) and, today even after many years, remains deeply impactful (Letters to Oprah, n.d.).

A two-phased, qualitative study was executed to understand the production-side experience that could inform the potential research questions relating to The Oprah Winfrey Show’s impact on the audience and explore the idea of Oprah’s legacy (Garner, 2021). The purpose of the study was to examine the insights from five executives who work or worked for Oprah Winfrey during the production of The Oprah Winfrey Show syndicated series (1986-2011). The secondary phase examined the database of The Oprah Winfrey Show from a meta-analysis perspective in terms of episodic titles and show category themes.

This qualitative research study included one-on-one, in-depth interviews (IDIs) with five key executives from Harpo Studios who played a senior integral role in show curation, marketing, public relations, and talent booking. The interview structure used a grounded theory, qualitative approach because this method employs an open-ended approach for uncovering aspects about how the social world works to garner insight (Wertz et al., 2011). The executive interviews explored some of the key components or considerations that were given to curating The Oprah Winfrey series, the emotional and personal experience of those involved, as well as their perspectives as to what would resonate with the audience.

The secondary phase was conducted post-hoc using a meta-analysis exploration of The Oprah Winfrey Show database. This analysis occurred post-executive IDIs to reduce potential interviewer bias while collecting the qualitative themes.

Qualitative In-Depth Interviews with Harpo Executives

From qualitative interviews with Harpo Studios executives (Garner, 2021), the power of the series’ longevity and the audience’s connection to the Oprah Winfrey brand, beyond the show itself, emerged as the primary themes.

These executives described The Oprah Winfrey Show as “more than a talk show,” using terms such as:

- “A national, daily conversation”

- “A mirror to the self and mind”

- “A guide map on how to transcend hardship”

- “A celebration of things that positively move us to tears” (Garner, 2021).

The executives’ sentiments largely echoed scholars’ work on Oprah and the parasocial interaction among consumers (Lofton & Weber, 2012; Loroz & Braig, 2015; Peck, 2010). The interviews also confirmed the narrative themes of self-growth, overcoming challenges, and personal transformation throughout the tenure of the show.

Meta-Analysis of The Oprah Winfrey Show

An additional goal of the study was to examine an existing dataset of program, titles, themes, and broadcast dates of The Oprah Winfrey Show to see if themes align with executive recollections. The database is proprietary, supplied by the Oprah Winfrey Network (OWN) with permission and contained no personal data. With access to The Oprah Winfrey Show (TOWS) database (Hapro, 2011), a lexical meta-analysis was run on both show titles and episodic category codes of all 4,561 episodes of the series; the analysis was run using Leximancer, a software system that provides in-depth text analysis to identify key concepts, stories, and relationships within a defined text set of data. The analysis for the show titles versus the episodic categories revealed some similarities, but it also highlighted several differences (Garner, 2021).

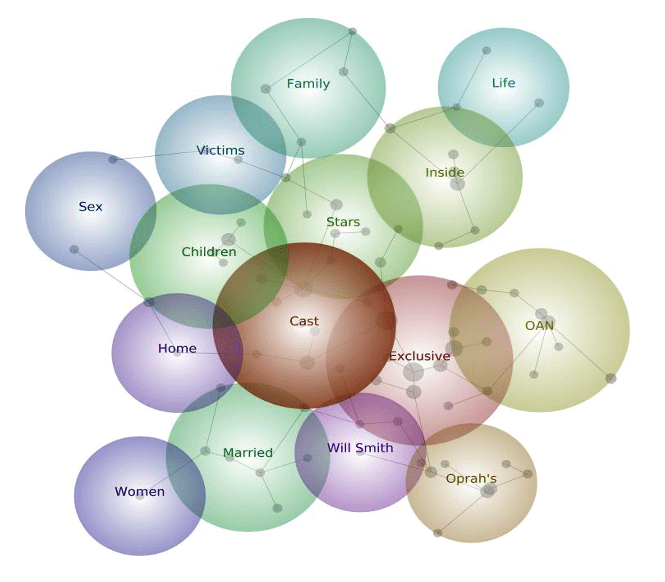

The meta-analysis of show titles revealed the highest frequencies, which were also connected to numerous other words in the titles, were for the words “cast” and “exclusive.” These connections were direct and indirect with their associative properties. Other words that garnered modest frequency included “Oprah’s Angel Network (OAN),” “inside,” “Oprah,” “stars,” “married,” “children,” and “family” (Figure 1). The primary finding on episode titles revealed the commercial nature of capturing the audience’s attention vis-à-vis direct language and salient messaging (Forscher et al., 2019).

Figure 1: Lexical Analysis of Episodic Titles

Note. Size of bubble connotes frequency attribution.

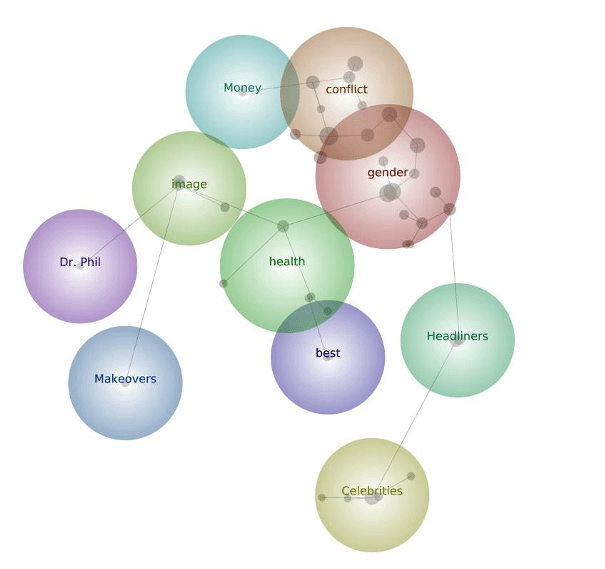

The meta-analysis of the show’s episodic categories, which were the themes and topical descriptions supplied by the producers to the TV show listing services, indicated some similar word choices (Figure 2). However, the foci of the word frequencies and the words’ connectivity centered largely around “gender,” “conflict,” and “celebrities” (Garner, 2021). Moreover, the former two (e.g., gender and conflict) generated the greatest degree of thematic connectivity— direct and indirect—to other lexical categories.

Figure 2: Lexical Analysis of The Oprah Winfrey Show’s Episodic Categories

Note. Size of bubble connotes frequency attribution.

This finding illustrated the social capital the show had with its audience in terms of cognitive uptake and consumer insight. Chua and Westlund (2019) note in their longitudinal study that “audience-centric engagement” has evolved to not only include content and business functionality but also metrics that impart “collaboration culture” and “platform counterbalancing” (p. 162). This meta-analysis of the TOWS database suggested the significance of the Oprah legacy which evolved from the television series in a linear, analog media experience to the multimedia empire it was in 2011 (when the show went off-air) and is today. Also, the top two words “gender” and “conflict” represent core deviational brand targets in terms of the thematic device which attracts viewers to engage with the show (Dweck, 2008; Kahneman, 2011; Mulder & Yaar, 2006). “Gender” was the most used categorical word, mentioned 1,727 times out of 4,561 episodes or in approximately 38%, and further underscored the unique resonance the series had with its female audience.

Additional high-word frequencies that occurred within the episodic category meta-analysis that were absent or muted in the title meta-analysis were “health,” “best,” “image,” and “money” (Garner, 2021). These words provided insight into how the show provided consumers with “best-life” guidance that both previous research from Nurfazrina (2016) and Loroz and Braig (2015) referenced in terms of consumer engagement and commerciality. Some words, such as “health,” “best,” and “image” also hinted at deeper psychological descriptive that shows’ messages may impart in terms of “non-conscious motives that can induce positive affect” (Van Cappellen et al., 2018, p. 77).

To address the research questions and hypotheses related to Oprah’s impact, a quantitative audience self-report survey collected responses to examine how reported emotional experiences and sense of connection were related to the audience’s self-perceptions of the show’s impact 10 years later (e.g., see Appendix A). This survey was fielded October 6-12, 2021.

Conclusion

While the audience Oprah assembled during the show continues to follow her on her newer media endeavors (i.e., Instagram, Twitter, Weight Watchers, and Oprah.com). This qualitative study examined the saliency of the messages that The Oprah Winfrey Show of how formal features of the production and consumer listing information imparted meaning. While the bulk of scholarly research on Oprah tilts toward a humanities and marketing perspective, recent communication and psychology studies on narrative have begun to shift. The interest and increased research in positive psychology extend several avenues for understanding what her talk show provided. Key findings from both phases (e.g., TV executive IDIs and lexical meta-analysis of show information) produced sentiment-informing questions for a larger consumer-based quantitative survey.

When Oprah was sunsetting her eponymous series (in 2011) she was dubbed as one of Time’s 100 most influential people in the world. Former media mogul Ted Turner (2011) penned the brief tribute, stating, “I have often said that if women ruled the world for the next 100 years, we’d all be better off. I have a feeling that with the possibilities at Oprah’s fingertips, we may be one step closer.” From the vantage point of this study, The Oprah Winfrey Show’s legacy is the evidence that media advocacy for socially conscious programming was, like Oprah, ahead of its time.

References

Chua, S., & Westlund, O. (2019). Audience-Centric engagement, collaboration culture and platform counterbalancing: A longitudinal study of ongoing sensemaking of emerging technologies. Media and Communication, 7(1), 153-165. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v7i1.1760

Dweck, C. S. (2008). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House Digital Inc.

Forscher, P. S., Lai, C. K., Axt, J. R., Ebersole, C. R., Herman, M., Devine, P. G., & Nosek, B. A. (2019). A meta-analysis of procedures to change implicit measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 117(3), 522-559. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000160

Garner, M. S. (2021). Narrative experience: Demystifying The Oprah Winfrey Show from a behind-the-scenes perspective (a qualitative examination).

Hapro. (2011). The Oprah Show Database. Hapro Studios, LLC.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Macmillan.

Letters to Oprah. (n.d.). https://www.oprah.com/oprahshow/letters-to-oprah/all

Lofton, K., & Weber, B. (2012). The legacies of Oprah Winfrey: Celebrity, activism, and reform in the twenty-first century. Celebrity Studies, 3(1), 104-105. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2012.644724

Loroz, P. S., & Braig, B. M. (2015). Consumer attachments to human brands: The “Oprah effect”. Psychology & Marketing, 32(7), 751-763.

Mulder, S., & Yaar, Z. (2006). The user is always right: A practical guide to creating and using personas for the web. New Riders.

Nurfazrina, H. (2016). Verbal communication analysis in The Oprah Winfrey Show. Indonesian EFL Journal, 2(2), 145-153. https://doi.org/10.25134/ieflj.v2i2.647

Pease, A., & Brewer, P. R. (2008). The Oprah factor: The effects of a celebrity endorsement in a presidential primary campaign. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 13(4), 386- 400. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161208321948

Peck, J. (1994). Talk about racism: Framing a popular discourse of race on Oprah Winfrey. Cultural Critique, 27, 89-126. https://doi.org/10.2307/1354479

Peck, J. (2010). The secret of her success: Oprah Winfrey and the seductions of self- transformation. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 34(1), 7-14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0196859909351145

Renfro, K. (2020). Oprah Winfrey is randomly surprising fans on Twitter with vacations, new computers, and other holiday gifts. Insider.com. Retrieved December 17, 2020 from https://www.insider.com/oprah-winfrey-surprising-fans-twitter-gifts-vacations-2020-12

Squire, C. (1994). Empowering women? The Oprah Winfrey Show. Feminism & Psychology, 4(1), 63-79. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353594041004

Turner, T. (2011). Oprah Winfrey. Time. http://content.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,2066367_2066369_20660 94,00

Van Cappellen, P., Rice, E. L., Catalino, L. I., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2018). Positive affective processes underlie positive health behaviour change. Psychology & Health, 33(1), 77-97. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2017.1320798

Wertz, F. J., Charmaz, K., McMullen, L. M., Josselson, R., Anderson, R., & McSpadden, E. (2011). Five ways of doing qualitative analysis: Phenomenological psychology, grounded theory, discourse analysis, narrative research, and intuitive inquiry (1st ed.). Guilford Publications. https://go.exlibris.link/6T24dm2K

Wilson, S. (2003). Oprah, celebrity, and formations of self. Springer.