The News Media and New Media: The Internet’s Effect on Civic Engagement

Jed D. Brensinger, Rebecca Gullan and Janis Chakars

Gwynedd-Mercy University

Abstract

This study utilized a self-report survey method to score participant’s feelings of civic engagement after having viewed the news media in print, online, or not at all for a period of 15 minutes. Participants were 359 undergraduate students who completed the experimental procedure during part of an allocated class time. The measure of civic engagement consisted of 3 different scales gauging civic responsibility, empowerment, and ability to dissent. The results indicate that having viewed the news media produces a significant difference is respondents’ civic responsibility (α=.01) and ability to dissent (α=.01). Print newspaper readers had the greatest level of civic responsibility, whereas online viewers produced mean scores below those of the control group. Pertaining to ability to dissent, online viewers had the greatest mean, with the control group producing the lowest mean, indicating that viewing the news media seems to increase one’s feelings of having the ability to dissent, though viewing it online increases it more so

Jed Brensinger completed the work for this article after receiving his BS in Psychology from Gwynedd-Mercy College. He is interested in technology’s impact on society, engagement, and the role of nature in the lifespan. He will begin pursing his MS in Environmental Social Science at the Ohio State University in Autumn 2014.

Jed Brensinger completed the work for this article after receiving his BS in Psychology from Gwynedd-Mercy College. He is interested in technology’s impact on society, engagement, and the role of nature in the lifespan. He will begin pursing his MS in Environmental Social Science at the Ohio State University in Autumn 2014.

Rebecca Gullan, Ph.D. is an Associate Professor of Psychology at Gwynedd Mercy University. Dr. Gullan is a licensed clinical psychologist whose research interests include empowerment, civic engagement, sense of belonging, and identity development during adolescence and emerging adulthood. Dr. Gullan is a reviewer for several peer-reviewed journals in psychology and has received grant-funding for her program development research.

Rebecca Gullan, Ph.D. is an Associate Professor of Psychology at Gwynedd Mercy University. Dr. Gullan is a licensed clinical psychologist whose research interests include empowerment, civic engagement, sense of belonging, and identity development during adolescence and emerging adulthood. Dr. Gullan is a reviewer for several peer-reviewed journals in psychology and has received grant-funding for her program development research.

Janis Chakars, PhD, is Assistant Professor, Communication Program Coordinator, and Chair of the Division of Language, Literature, and Fine Arts at Gwynedd Mercy University. His research has appeared in American Journalism, Journalism History, the Central European Journal of Communication, and elsewhere.

Janis Chakars, PhD, is Assistant Professor, Communication Program Coordinator, and Chair of the Division of Language, Literature, and Fine Arts at Gwynedd Mercy University. His research has appeared in American Journalism, Journalism History, the Central European Journal of Communication, and elsewhere.

The newspaper has long been seen as a critical point of connection within one’s community. However, in an increasingly electronic and global age, the grasp of this traditional news medium is weakening and many have suggested that along with it will go many of the positive effects of an engaged and informed public. Others argue that consumers have not turned away from all news media, but have instead migrated to different avenues for receiving it. Thus, a 2012 Pew Research Report found that the audience for online news media grew 17.2% from 2010 to 2011 alone. In this same year, print newspapers saw a loss of 4% in audience, on top of a 5% drop in the previous year. Many Americans have now become fully assimilated to the digital era, with 23% of the population receiving the news on multiple digital devices (Mitchell, Rosentiel, & Christian, 2012). Given this shift in the mode of news consumption, the importance of understanding these changing effects is critically important. Specifically, the present study explores the effects of changing news media on civic engagement. It investigates whether how we receive the news, not just what news we receive, affects our sense of civic engagement.

Civic Engagement

In recent years, the concept of civic engagement has surged in popularity. A Google search for the term yields about 17.7 million results in about half of a second, whereas the same search only nine years ago found 383,000 citations1. Previous use of the term has encompassed political involvement, collective action, social change, social capital, citizenship, and social relationships to name just a few. In Addler and Goggin (2005), noted political scientist Michael Delli Carpini provides a broad definition of civic engagement, stating thus:

Civic engagement is individual and collective actions designed to identify and address issues of public concern. Civic engagement can take many forms, from individual voluntarism to organizational involvement to electoral participation. It can include efforts to directly address an issue, work with others in a community to solve a problem, or interact with the institutions of representative democracy. Civic engagement encompasses a range of specific activities such as working in a soup kitchen, serving on a neighborhood association, writing a letter to an elected official or voting.

Widespread research suggests that many of these types of civic engagement may be waning, and that it is important to consider the role of altering media consumption in why and how these changes are occurring. Mostly notably, political scientist and social critic Robert Putnam focuses on the loss of social capital and its impact on civic engagement (Putnam, 2000). Although Putnam’s research still remains a foundation upon which much research in civic engagement has been built, it too has its critics in regards to his assumptions made (Policy Studies Associates, 2003; Skopcol & Fiorina, 1999; Youniss, et al., 2002).

Effect of Traditional Newspapers on Civic Engagement

A number of studies have demonstrated the positive effects of traditional newspapers on civic engagement. For youth, civic engagement can be linked to being informed of issues, a task which has traditionally been taken up by local newspapers. In one such study teens who used newspapers in the classroom and for homework assignments were more likely to engage in civic expression than those who did not do either of these activities. Apart from these immediate effects, research also suggests that programs that encourage teens to read newspapers also facilitate civic engagement 10 to 15 years later (Newspaper Association of America [NAA], 2008). Similarly, research has found positive correlations between campus newspaper readership among college students and various campus ties and activities (Hoplamazian & Feaster, 2009). Community newspaper readership has also been shown to positively correlate with a sense of social cohesion, which relies on building social bonds based upon relationships and shared beliefs in the creation of a collective unit (Yamamoto, 2011).

Even small newspapers can make civic life more vibrant. In recounting the closing of the Cincinnati Post, researchers found several changes among Kentucky’s municipal politics. Such changes included fewer voters and candidates for city council, city commission, and school board. In the case of voter turnout, this diminished showing remained for three years after the Post’s closing (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2009). Among reasons given for not engaging in civic activities were being too busy, having other priorities, lacking personal resources, and having doubts about what could be accomplished (NAA, 2008).

Effect of the Internet on Civic Engagement

As the pervasiveness of the internet has grown, it seems only appropriate that the medium would grow to have effects beyond the online community. One such area that research has attempted to link to internet use is civic engagement. As the amount of research on this topic has increased, differing viewpoints have emerged, easily being separated into three camps; cyber skeptics, reinforcement theorists, and mobilization theorists.

Cyber skeptics are characterized by their findings that show no positive correlation between internet use and civic engagement, and often even cite negative relationships between the two. Research in this arena often cites studies that find limited correlations between use of the internet and political empowerment or civic engagement. However, such research also often attempts to link any generalized use of the internet with measures of civic engagement (Scheufele & Nisbet, 2002). Attempting to categorize technologies as diverse as instant messaging, blogging, social media, wiki sites, eBooks, and the World Wide Web as a singular device makes it almost certain that any positive effects resulting from one subgroup will likely be lost when averaged together with other technologies used for different purposes. Online political forums may in fact increase civic engagement, while social media, blogs or other destinations may not; just as reading the world news section of a newspaper likely increases one’s political interest, while the comics page may not.

More confident in the internet’s ability to increase civic engagement than the cyber skeptics, but less so than mobilization theorists, lay the reinforcement theorists. It is their contention that although the internet may not prompt civic engagement among the disengaged, it simply increases participation levels for the already engaged (Bimber, 1999; Kruger, 2002). Many studies point to increased political interest and participation as a direct result of the internet’s availability, much as any informational tool would allow interested parties to gather more information (Johnson & Kaye, 2003; Xenos & Moy, 2007). However, although the internet is certainly ripe with information to be gathered it also acts as a new forum on which interested parties can meet.

Those who would be considered mobilization theorists cite the internet’s ability to reach those formerly disenfranchised through prohibitive costs, distance, or disability as a path toward greater civic engagement. They cite research that concludes the internet is able to jump-start traditionally inactive populations and characterize the internet as a virtual breeding ground for doing so (Barber, 2001; Norris, 2001; Weber, Loumakis & Bergman, 2003). This new area of social interaction that is the internet comes with increased methods of engaging in civic life, such as signing online petitions, participating in online discussions and groups, and voicing opinions to audiences that might not otherwise be available to all people (Polat, 2005; Delli Carpini, 2000). Much of this research has dealt with political empowerment and the internet, especially in relation to involvement around significant elections. The increased opportunities offered via the internet to engage in discussion and information gathering have been linked to increased feelings of self-efficacy, increased trust in the government, and overall increases in political participation (Johnson & Kaye, 2003; Weber et. al, 2003).

Engagement, Empowerment, and Dissent

One of the internet’s strengths lies in the ability of its users to gather information that might not have previously been accessible to them. With this increased awareness often comes a new level of activism. However, an increased level of awareness in regard to problems facing environmental, social, or health issues alone has not been shown to induce action (Fiske, 1987; Schofield & Pavelchak, 1985; Horvath, 1999). The next required step in using engagement to fuel activism is empowerment.

A good deal of research has been done that links being engaged within a community or group and feeling empowered. Zimmerman, a noted researcher in empowerment describes psychological empowerment as: “the connection between a sense of personal competence, a desire for, and a willingness to take action in, the public domain.” Greater participation in community activities and engagements has been shown to correlate to increased feelings of psychological empowerment (Zimmerman & Rappaport, 1988).

In this experiment, Zimmerman’s “willingness to take action” is used to introduce the concept of dissent as a next logical progression following engagement and empowerment. Dissent can be thought of as taking an opposing view, disagreeing with a majority, or having a difference of opinion. In many instances dissent may be focused against a political party, government, or other sizeable institution. However, this is not always the case, and dissenting opinions can be found on most issues, no matter their size. Dissent is typically aired in public places, as it is through their being public that dissenters are able to share their opinions and possibly convince others of the accuracy of their dissenting opinions (McCarthy & McPhail, 2006).

In recent years public spaces have been under attack, with many laws limiting the definition of ‘public’ and imposing rules as to where and how dissenting opinions may or may not be expressed (McCarthy & McPhail, 2006; Roberts, 2008).While many previously public places such as sidewalks and parks have become privatized, thereby limiting their use as areas for protest, the internet has emerged as a forum where censure is discouraged. In fact, the internet not only accepts dissenting opinions, but often celebrates them, offering multiple opportunities for users to express their opinion of what they read and view online. Not only have forums evolved for those from nearly every political, philosophical, and religious orientation, but opportunities for user generated comments have come to be increasingly popular within the news media, even as journalists’ enthusiasm at the new technology have tempered (Nielson, 2012).

Research has previously been focused on how the news media, especially in its print form has been able to impact civic engagement. Still, the internet’s impact on civic engagement is debated by many researchers and requires further testing. With that in mind, this research attempts to answer the following:

RQ: Does the interface through which people receive news media have an effect on their civic engagement? And if so, in what way?

The interactions that exist as a result of civic engagement’s effect on empowerment have been well documented, but what remains to be seen is how this resulting empowerment can be put to use. Taking into account Noelle-Neumann’s theory of The Spiral of Silence, the airing of dissenting opinions in public without repercussions, as is possible with internet commenting, should allow for the empowerment of those with dissenting opinions (Noelle-Neumann, 1974). It is based upon these connections made between previous research that the following hypotheses are made:

H1: Consumers of news media will have differing degrees of feelings of empowerment, ability to dissent, and civic responsibility based upon the interface through which the media is received(print versus online).

H2: Readers of online news media will feel more empowered, have greater levels of civic responsibility, and feel more able to dissent than those who read print media.

Methods

Participants

Subjects were selected from 376 students recruited from fourteen introductory level classes at a small Catholic college. Participants included 87 males and 285 females (with 4 not selecting gender) between the ages of 18 and 52. The average age of all student participants was 20.7 years (SD = 4.98). Of the 376 participants completing the survey, data from 359 subjects were analyzed. Those participants excluded from analysis were not within 2 standard deviations of the mean in regards to age. This reduced the average age of all subjects to 19.75(SD=2.17) to create a more homogenous group by removing outliers.

Researchers obtained approval to administer their study during class time in various introductory level courses, none of which was about media consumption. Students who provided written consent to participate were assigned quasi-randomly at the classroom level to one of the two experimental conditions (internet or newspaper) or the control condition (no news consumption). Classes held in computer laboratories were assigned to the internet condition and those without computers were randomly assigned to either the newspaper or the control condition. Of all eligible students, over 95% provided written consent to participate.

Measure Descriptions

For the purpose of the present study, engagement in civic life was made up of measures of civic responsibility, empowerment, and perceived ability to dissent. These measures were chosen in regard to the connections made in the introduction of this research. In addition to these three measures, basic information on participants overall news consumption and interests were assessed. Civic responsibility, or one’s belief that they ‘ought’ to act in a specific manner, relates to their intent to be involved in civic life. Although many people may not always act in ways that they believe they should, a shared sense of civic responsibility acts as the foundation upon which intents are turned into actions. Empowerment, or one’s belief in his or her own sense of efficacy in community problems, acts as the next building block of civic engagement. Once a person knows what concerned citizenship entails, the next step towards that goal is acting in that manner. Without a belief that their actions can evoke change, people feel powerless and regardless of intent, can easily become cynical of their ability to produce any action. Lastly, one’s ability to dissent offers citizens a path to action after having garnered an understanding of what should be done and a belief that such things can be done. Dissent allows citizens to express opinions that may be unpopular as well as question traditional wisdom and methods of doing things. As such, these three variables are used in this study as components of civic engagement as a means to developing a more concerned citizenship.

Media use and preference

Three questions sought to gauge participants’ frequency of news media viewership, with statements including “I read/viewed news media today/yesterday/within the last week,” to which participants answered “yes” or “no.” The next three questions related to media preference and asked the participant from what sources they commonly received their news media, their reasoning for preferring this source, and in what area of the news media they were most interested(e.g. world news, local news, sports, etc.).

Civic responsibility

Civic responsibilitywas measured with a ten item measure asking participants to indicate on a four point Likert scale their feelings of personal responsibility for helping those in need or working for worthy causes. This measure has established reliability and validity from previous use in research with adolescent populations (Lakin & Mahoney, 2006; Gullan, Power, & Leff 2013). Internal consistency in previous use was borderline (α = .69) with the current use reaching a moderate level (α = .86). Items addressed the extent to which respondents felt they were responsible for their community and its members (e.g., “ It is important that I help those in need” and It is important that I work to resolve issues or problems facing my community”). Responses for the current study ranged from one being “not at all important” to four “very important.” A sum civic responsibility score was computed for analysis by adding all ten items of the civic responsibility scale. Scores ranged from 10 to 40, indicating that some participants rated all items as “not at all important” while others rated all items as “very important.”

Participant sense of personal power in community issues was measured with a ten item, four point Likert scale that has been used in previous research (Lakin & Mahoney, 2006: Gullan, Power, & Leff, 2013).Items addressed the extent to which respondents felt they were able to impact community problems or issues (e.g., “I can do something about problems with gun violence” and “I can do something about litter, graffiti or dirtiness”). Responses ranged from one “strongly disagree” to four “mostly agree.” A total empowerment score was computed in the same manner as described in the civic responsibility condition. In this condition, scores again ranged from 10 to 40, indicating that some participants strongly disagreed on all matters, while others mostly agreed on all matters. Internal consistency was moderate, being slightly greater that reached in previous use (current α = .90, previous α = .83)

A seven question survey was developed for the present study to assess participants’ feelings of having a voice or being able to express their approval or disapproval of the news media (e.g., “I feel as though I could express my support for the things I read/view in the news media,” and “I would consider writing a comment refuting the things I read/view in the news media”). For these questions, participants were asked to select either “true” or “false”in accordance with how they felt. A total dissent score was computed for each participant by adding the seven scores from the items that made up the dissent scale. Scores ranged from zero, indicating that participants didn’t feel able to dissent or express their opinions, to seven, with participants believing they could express their approval or disapproval of the news media. Internal consistency for this measure was lower than reached on the other scales used in this research, but was acceptable (α = .64).

Procedure

Upon arrival at the classroom, the experimenter provided a brief overview of what the study would entail. Experimental group participants who provided written informed consent were then asked to either look through printed copies of the local metropolitan newspaper (The Philadelphia Inquirer; N= 6 classrooms; n=173 participants) or to view the online equivalent (philly.com; N=4; n=78) for fifteen minutes. After having done so they were asked to complete the survey as detailed above. A control group (N=4; n =108) took the survey without receiving immediate exposure to either type of news media.

No requirements were given as to what articles or areas of the news media to attend to, but participants were asked to forgo other tasks and view only the print newspaper or philly.com for the designated amount of time. Those in the control and newspaper conditions were seated in standard lecture halls or classrooms, with all participants facing forward, nearly parallel to the front of the room. Those in the internet condition sat in an open classroom designed for use with desktop computers. Each participant sat with a computer directly in front of them with their body oriented perpendicular to the front of the room where an instructor might stand. The person administering the survey asked that the participants focus entirely on reading from their selected medium and not engage in conversation with others in the room for the duration of this time.

Results

Descriptives

Among all study participants a majority stated that they did not view any news media besides that required for the experimental groups on the day they answered the questionnaire. Rates increased when taking into account the possibility of viewing news media in the last two days, with 51% having viewed some form of news media. When allowing for an entire week to view news media, 79% of participants stated that they had done so.

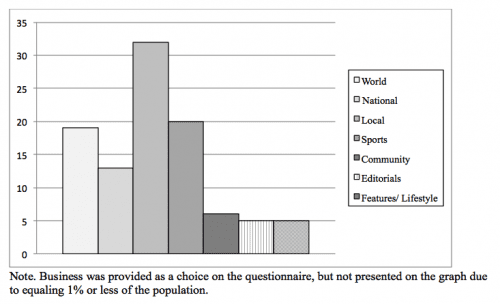

A majority of participants stated that they most commonly received their news media online (45%), followed by television (39%), radio (12%), and the newspaper (4%). The vast majority of participants (85%) selected convenience as their reason for choosing this method of news media consumption, with others citing preferred content (10%), other reason (3%), and cost (2%). Participants also chose up to two areas of interest in the news media which are presented in figure 1.

Figure 1. Percentage of Respondents Interested in Differing Areas of the News

For section two of the questionnaire, the majority of participants (55%) felt that their opinion was reflected in the news media that they view. The majority of respondents (58%) felt that the news media does not do a good job of presenting both sides of an issue in its reporting. An overwhelming majority of participants (89%) also agreed that they knew how to go about expressing their opinion of what they viewed in the news media.

Primary Analyses

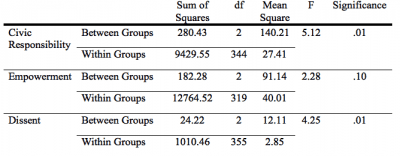

A single One Way Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) test was performed using SPSS 10. Total scores for Civic Responsibility, Empowerment, and Dissent were used as Dependent Variables while groups (control, print media, and online media) were entered as a factor. For the measure of Civic Responsibility statistical significance was reached, F(2, 344) = 5.12, p = .01, with those in the Newspaper group having higher mean scores than both the control and internet conditions(32.13, 30.46, and 30.17 respectively). This indicates that in viewing the news media online, participants actually exhibit lower levels of civic responsibility than those who have not viewed any news media.

Significance was not reached on the Empowerment measure, although a trending pattern was discerned, F(2, 319) = 2.28, p = .10, with the print and online conditions producing higher mean scores than the control group(26.12, 24.81, and 24.50 respectively). Significance was reached for the measure of dissent, F(2, 355) = 4.25, p = .01.This indicates that those in the online group reported higher mean scores than did those in both the print and control conditions(4.83, 4.72 and 4.19 respectively). Means scores, standard deviations, and standard errors for all conditions are presented in table 1. MANOVA results for all measures of civic engagement are presented in table 2.

Table 1. Means and Standard Deviations for Measures of Civic Engagement

Table 2. MANOVA Results for Experimental Groups

Post hoc t tests were performed to analyze differences between the three conditions. All comparisons for the measure of Civic Responsibility were found to meet statistical significance at the p = .01 level. Significance was not found for interactions between the internet and newspaper conditions in regard to Empowerment (p=0.15) and Dissent (p=0.61). The remaining conditions for Empowerment and Dissent each reached significance at the levels of p=0.05 and p=0.01 respectively.

Discussion

In an ever-advancing technological world, changes in the medium through which the news is consumed are inevitable. The internet as a medium has revolutionized how people seek out and consume information. It is no longer a question as to whether the internet has or is changing the face of the news media; it has already been shown to do so. Many newspapers have shifted their content to online and begun offering combination subscriptions, bundling print and online access to provide news content at all times of the day. What still largely remains to be better understood is how this impact might change communities as a consequence. While many researchers have sought to better understand this impact through gathering information on media preference and habit, this study is one of the first experimental studies on the relative impact on internet vs. print media on civic engagement.

It is as a result of this melding of psychological theories, perspectives, and methods with communications and media use research that this study arrives at its results. With this perspective has come a new way of conceptualizing civic engagement, as used in this study; consisting of measures of civic responsibility, community empowerment, and a perceived ability to dissent. The main purpose of this study was to determine whether the interface through which readers accessed the news media would have an effect on their level of civic engagement. In exploring this question, the researchers partially supported H1, as statistically significant differences were found between participant groups in relation to measures of Civic Responsibility and ability to Dissent. However, the measurement of Empowerment did not reach statistical significance at any meaningful level, showing only a trending effect.

In examining H2, only the measure of perceived ability to Dissent reached statistical significance as expected, with the Internet condition having statistically significantly higher means than the Newspaper and Control groups. This points to Internet news media users as being more willing to express their dissenting opinions than those in the Newspaper condition. Various reasons could be offered for this finding, including the higher frequency of comments sections available to internet news media users and the immediacy with which such comments become available to others. Traditional print newspapers require readers who wish to express their opinions to write letters to the editor with no guarantee that they will be published along with a timeframe that likely seems an eternity to many digital natives. Alternately, the availability of posting anonymously reduces any fear of retaliation or isolation that might be incurred from expressing a dissenting opinion.

H2 was not supported for the measure of Civic Responsibility, although the measure was able to reach a level of statistical significance equal to that of the measure of Dissent (p=.01). The relationship observed between the Newspaper and Internet conditions was the opposite of that anticipated, with the Newspaper condition producing a higher mean score (32.13) than the Control (30.46) and Internet (30.17) conditions. More striking than the reversal of the direction of the hypothesis was the finding that the Internet condition produced a lower mean than the Control group. This seems to signify that not only does receiving news media via printed newspaper increase one’s feelings of civic responsibility, but that doing the same via the internet may actually work to decrease these feelings.

This result contradicts much previous research that has attempted to link internet use with increased civic engagement. One stark difference in this study compared to the majority of its predecessors is its employment of an experimental rather than a correlational method. Secondly, this specific measure for which the opposite of the anticipated effect was found is only one of three measures that make up this study’s overall measure of civic engagement. However, despite its being labeled as a measure of Civic Responsibility, each of its ten questions fits Delli Carpini’s definition of civic engagement as “individual and collective actions designed to identify and address issues of public concern.”

Although this specific measure makes up only one third of the study’s findings, it may be the most important in its findings and relation to civic engagement. The measure of Dissent may require further development for use in future research and further grounding in theory. While the Empowerment scale has been used previously, perhaps future work would do well to not only explore empowerment in community situations as this research did, but also to delve into personal or psychological empowerment. Among other limitations include the use of traditionally college-aged students, a demographic excessively used in research. Still, it is within this age range that citizens first become able to vote, as well as begin shaping their long-lasting political beliefs and voting patterns, making them a prime target for the news media. Lastly, the study was limited by the amount of time readily available during a typical class period, which meant participants were only able to view the news media for fifteen minutes.

In future research this available time period could be expanded, allowing for additional and more in depth involvement with the news media than was possible in the current study. This might also allow for the exploration of a dosage effect of the news media and its relation to civic engagement. There is still much research to be done on the topic of the news media and civic engagement, and although this study attempted to further glean information about this complex relationship, its mixed results may have only further muddied the waters. Future studies would do well to further add more experimental research to the wealth of correlational studies already available on this topic and further integrate findings from disciplines beyond communications for a more holistic understanding of the subject.

Perhaps the greatest direction of future research into new technologies and civic engagement lies simply in attempting stay afloat amongst the increasing current that is an ever-changing technological landscape. As different social media and networking websites progress throughout their own lifecycles, ways of communicating and sharing the news media rise with the tide (Greer & Yan, 2011). Many users have already taken to posting, sharing, and commenting on the news media through social networking sites such as Facebook and Twitter, which will likely continue to expand into the future (Glynn, Huge, & Hoffman, 2012). That the news media has had an effect on civic engagement is no longer up for question, but its ability to continue doing so in the future may be.

References

Adler, R., & Goggin, J. (2005). What do we mean by “civic engagement”?. Journal of Transformative Education 3(3). 236-253. doi:10.1177/1541344605275792

Barber, B. R. (2001). The uncertainty of digital politics: Democracy’s uneasy relationship with information technology. Harvard International Review 23. 42-47.

Bimber, B. (1999) The internet and citizen communication with government: Does the medium matter? Political Communication 16.423-425. doi:10.1080/105846099198569

Delli Carpini, M. X. (2000). Gen.com: Youth, civic engagement, and the new information environment. Political Communication 17(4). 341-349. doi:10.1080/10584600050178942

Fiske, S. T. (1987). People’s reactions to nuclear war: Implications for psychologists. American Psychologist 42(3). 207-217. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.42.3.207

Glynee, C. J., Huge, M. E., & Hoffman, L. H. (2012). All the news that’s fit to post: A profile of news use on social networking sites. Computers in Human Behavior 28(1). 113-119. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2011.08.017

Greer, J. D., & Yan, Y. (2011). Newspapers connect with readers through multiple digital tools. Newspaper Research Journal 32(4). 83-97.

Gullan, R. L., Power, T. J., & Leff, S. S. (2013). The role of empowerment in a school-based community service program with inner-city, minority youth. Journal of Adolescent Research 28(6). 664-689. doi:10.1177/0743558413477200

Hoplamazian G., & Feaster, J. (2009, May). Different news media, different news seeking behaviors: Identifying college students patterns of news media use. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Communication Association, Chicago, Illinois.

Horvath, P. (1999). The organization of Social Action. Canadian Psychology40(3). 221-231.

Johnson, T. J., & Kaye, B. K. (2003) A boost or bust for democracy? How the web influenced political attitudes and behaviors in the 1996 and 2000 presidential elections. Press/Politics 8(3). 9-32. doi:10.1177/1081180X03252839

Kruger, B. (2002). Assessing the potential of internet political participation in the United States: A resource approach. American Politics Research 30. 476-498. doi:10.1177/1532673X020300005002

Lakin, R., & Mahoney, A. (2006). Empowering youth to change their world: Identifying key components of a community service program to promote positive development. Journal of School Psychology 44(6). 513-531. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2006.06.001

McCarthy, J. D. & McPhail, C. (2006). Places of protest: The public forum in principle and practice. Mobilization: An International Quarterly 11(2). 229-247.

Mitchell, A, Rosentiel, T., & Christian, L. (2012). Mobile devices and news consumption: Some good signs for journalism. The state of the news media 2012. http://stateofthemedia.org/2012/mobile-devices-and-news-consumption-some-good-signs-for-journalism/

National Bureau of Economic Research. (2009). Do newspapers matter? Short-run and long-run evidence from the closure of the Cincinnati Post. (Working Paper 14817). Cambridge, MA: Author. http://www.nber.org/papers/w14817

Newspaper Association of America [NAA]. (2008). In search of lifelong readers. http://www.naa.org/docs/Foundation/YouthMediaDNA_revised.pdf

Nielson, C. (2012). Newspaper journalists support online comments. Newspaper Research Journal 33(2). 86-100.

Noelle-Neumann, E. (1974). The spiral of silence: A theory of public opinion. Journal of Communication 24(2). 43-51.

Norris, P. (2001) Digital divide: Civic engagement, information poverty, and the internet worldwide. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Polat, R. K. (2005). The internet and political participation: Exploring the explanatory links. European Journal of Communication 20(4) 435-459. doi:10.1177/0267323105058251

Policy Studies Associates Inc. (2003, April).Social capital, civic engagement and positive youth development. Washington, DC. http://www.policystudies.com/studies/?id=57

Putnam, R. (2000).Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community.New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks.

Roberts, J. M. (2008). Public spaces of dissent. Sociology Compass 2(2). 654-674. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9020.2007.00074.x

Scheufele D. A., & Nisbet, M. C. (2002). Being a citizen online: New opportunities and dead ends. Press/Politics 7(3). 55-75.

Schofield, J., & Pavelchak, M. A. (1985). The day after: The impact of a media event. American Psychologist 40(5). 542-548. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.40.5.542

Skopcol, T., & Fiorina, M. P. (1999). Making sense of the civic engagement debate. In T. Skopcol & M. P. Fiorina (Eds.), Civic engagement in American democracy (pp. 1-23). Washington DC: The Brookings Institution Press.

Weber, L. M., Loumakis, A., & Bergman, J. (2003). Who participates and why?: An analysis of citizens on the internet and the mass public. Social Science Computer Review 21(1). 26-42. doi:10.1177/0894439302238969

Xenos, M., & Moy, P. (2007). Direct and differential effects of the internet on political and civic engagement. Journal of Communications 57(4). 704-718. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2007.00364.x

Yamamoto, M. (2011). Community newspaper use promotes social cohesion, Newspaper Research Journal 32(1) 19-33.

Youniss, J., Bales, S., Christmes-Best, V., Diversi, M., McLaughlini, M, & Silbereisen, R. (2002). Youth civic engagement in the twenty-first century. Journal of Research on Adolescence 12(1). 121-148.

Zimmerman, M. A., & Rapparport, J. (1988). Citizen participation, perceived control and psychological empowerment. American Journal of Community Psychology 16(5). 725-750.

Footnotes

[1] Google search conducted on March 30, 2014. Previous search data relating to the term found in Adler and Goggin, 2005.