Prosocial Video Game Effects

Darcia Narvaez, PhD

Bradley Mattan

Carl MacMichael

Mary Squillace

University of Notre Dame

ABSTRACT:

ABSTRACT:

Violent video games are known to significantly increase aggressive thoughts, feelings and behavior (Anderson, Gentile & Buckley, 2007). The effects of a prosocial video game were examined here. here were three video game conditions: violent (killing bandits), helping (saving people from dying by administering medicine), or neutral (collecting bags of gold), and two control conditions (game expectant but no game played, and no game). In the game playing conditions, participants played ten minutes of a video game built with tools from Neverwinter Nights and tried to earn points by carrying out the assigned task. All participants then completed three stories which were scored for prosocial, aggressive and neutral responses. MANOVA analyses showed a significant effect for the helping condition in increasing prosocial responses. There was no significant difference across conditions for aggressive responses. Findings are discussed in terms of how a helping-oriented game may promote a prosocial expectancy bias.

Darcia Narvaez is Executive Director of the Center for Ethical Education at the University of Notre Dame. She is an Associate Professor in the Department of Psychology.

Darcia Narvaez is Executive Director of the Center for Ethical Education at the University of Notre Dame. She is an Associate Professor in the Department of Psychology.

Bradley Mattan is an undergraduate student in psychology and philosophy at the University of Notre Dame.

Carl MacMichael is an undergraduate student in psychology and philosophy at the University of Notre Dame. He is a recent graduate of the University of Notre Dame and served on this research team.

The authors appreciate the help that the Notre Dame Moral Psychology Lab members have provided in bringing this project to fruition. Our special thanks go to Anna Gomberg and Ray Salinas.

For some decades, it has been established that exposure to violent entertainment media increases aggression (e.g., Anderson & Bushman, 2001). Studies inside and outside the laboratory show that violent media increase aggressive thoughts, feelings and behaviors (e.g., Anderson & Bushman, 2001; Gentile, 2007). The effects of prosocial media on behavior have been studied much less. Here, the effects of playing a prosocial video game were contrasted with the effects of playing a violent or neutral video game.

Violent media influence behavior in the immediate term and in the long term. Exposure to violent media leads to greater degrees of self-reported, teacher-reported, and peer-reported aggressive behaviors (e.g., Anderson & Dill, 2000). Violent media use leads to desensitization to violence and to the suffering of others, increases fearfulness of the world, and promotes the attribution of hostile intentions to others (e.g., Anderson, Berkowitz, Donnerstein, Huesmann, Johnson, Linz, 2003; Cantor, 1998; Hogan, 2001). Moreover, long-term effects of childhood exposure to violent media include a greater likelihood to commit interpersonal violence and to engage in criminal behavior as an adult (Huesmann, Moise, Podolski, & Eron, 2003; Johnson, Cohen, Smailes, Kasen, & Brook, 2002; Kunkel & Zwarum, 2006).

Although there are fewer studies of violent video games than of other violent media, research to date indicates that they promote an equal if not greater amount of aggression (Anderson et al., 2003; Bushman & Anderson, 2002; Anderson, Gentile, & Buckley, 2007; Gentile & Anderson, 2006). For example, Bushman and Anderson (2002) examined whether brief exposure to violent video game playing increased a hostile expectation bias—“the tendency to expect others to react to potential conflicts with aggression” (p. 1680). Participants were randomly assigned to a violent or a non-violent game condition. After playing for 20 minutes, participants completed story stems about potential conflict situations. Participants in the violent game condition were more likely to describe the main character as behaving, thinking and feeling aggressively than those in the non-violent condition.

A meta-analysis conducted by Anderson and Bushman (2001) combined the effects across video game studies on five types of behavior: physiological arousal, helping behavior, aggressive affect, aggressive cognition and aggressive behavior. Except for helping behavior which decreased significantly, all other variables increased significantly, and no moderator effects for age, sex, or type of study were found. A subsequent meta-analysis examining issues of methodology on a larger sample of studies showed that methodologically-weaker studies obtained smaller effect sizes than methodologically stronger studies, but in the same direction, suggesting that the effects of violent videogames has been underestimated (Anderson 2004).

Gentile and Anderson (2007) suggest that violent video games may have a greater influence on behavior than violent television for several reasons, one being that the player identifies consistently with a violent character. Moreover, violent games offer more active and repetitive practice of whole sequences of violent behavior, from start to finish, leading to greater learning. Rewards for violent action increase aggression in the game, and teach positive attitudes towards the use of force and persistence at violent behavior. Furthermore, a climate of continuous violence, such as that offered by video games, may be more influential on behavior than media in which violence is relieved by non-violent story events (e.g., commercials during violent television programming).

The General Aggression Model (GAM) is one of the predominant theories explaining the effects of violent media. The GAM “integrates existing theory and data concerning the learning, development, instigation and expression of human aggression” (Anderson & Dill, 2000, p. 773). Repeated playing of violent video games builds and reinforces aggression-related knowledge structures such as aggressive attitudes, aggressive behavior scripts, aggressive perceptual and expectation schemas, and leads to desensitization towards the needs and feelings of others. These aggressive schemas and attitudes lead to an increase in aggressive personality and a hostile expectation bias towards others (Bushman & Anderson, 2002). In fact, fMRI studies find specific brain functioning effects from violent media exposure. For example, when completing the Counting Stroop task, the brains of normal adolescents who had greater exposure to violent media (television and video games, self and parent reports) resemble the brains of aggressive adolescents with diagnosed conduct disorders; there was little activity in frontal lobe regions for either group, regions activated in those who had low exposure to violent media (Mathews, Kronenberger, Wang, Lurito, Lowe, & Dunn, 2005).

Not only do violent video games promote aggressive behavior but they also seem to inhibit prosocial orientations like empathy and aversion to violence. For example in a study of elementary school children, exposure to video game violence was associated with considerably lower empathy when compared to other forms of violent entertainment or exposure to real-life violence (Funk, Baldacci, Pasold, & Baumgardner, 2004). Funk and colleagues hypothesized that the greater tendency for violent games to reduce prosocial behaviors may be because they are more highly engaging than other forms of entertainment and can easily be translated into fantasy play. The behavior modeled in the games is later imitated in play.

There are few studies of prosocial video game effects. In one study, Chambers and Ascione (1987) compared the effects of a violent video game (boxing) with a prosocial video game (Smurfs rescue) on donating and helping behavior in 3rd -8th grade students. When compared with a neutral condition, students in the aggressive condition were less apt to donate nickels or sharpen pencils for the experimenter than those in the other conditions, but there was no difference in behavior between the prosocial and neutral conditions. It was speculated that the Smurfs rescue game may have been more like a violent game than a prosocial game because of the numerous obstacles to be overcome during the rescue. Clearly more careful laboratory studies are needed to examine the specific effects of prosocial media.

The Present Study

Although research into the effects of prosocial media exposure may be increasing, there are no studies to date that investigate subsequent feelings and thoughts after playing prosocial video games (Hogan & Strasburger, in press). For the present study, the Bushman and Anderson (2002) design was extended by including a helping video game condition along with violent and neutral conditions. The effects of condition on story stem completions were compared. It was hypothesized that playing the helping game would increase prosocial responses in comparison to the other conditions. It was also expected that the violent condition would prime aggressive responses in comparison to the other conditions, replicating previous findings.

Method

Participants

Participants were 125 undergraduate student volunteers, freshmen to seniors, from a mid-sized private university in the American Midwest who received course credit for their participation. Several participants were eliminated from the analyses for the following reasons: one gave three times as many answers to each story as required; four gave too few answers; four were unable to play the game properly (it froze up or they got caught in a corner). So the final number of participants included in the analysis was 116. There were 57 males (mean age = 19.53; 18 minority) and 59 females (mean age = 19.61; 15 minority).

Materials

Video Game Conditions. There were three video game conditions, violent, helping, and collecting (neutral). The games were constructed with tools from the video game Neverwinter Nights (original version). In all three conditions, participants tried to earn points as they moved through rooms in a building. In the violent version the participant earned points by killing marauding bandits with a sword before they got away with the gold. When a bandit was killed the participant heard a slicing sound and grunt and they confiscated the bandit’s gold. Sometimes a bandit needed to be hit multiple times before he would die. The helping version required the participant to administer medicine to ill characters thereby healing them. When a person was given medicine, the participant heard the healed person express a “thank you” and collected a thank-you note. Sometimes the sick needed to be given several doses of medicine before healing occurred. In the collecting version, participants gathered as many bags of gold as they could before the bags were taken by mice. When a bag was picked up, the participant heard a clinking sound. The games were constructed to be equally arousing; participants were pressured to act to get points before it was too late (before bandits left, bags were grabbed by mice, or people died). As more and more instances of the task were completed, the game character became stronger and faster at task completion. Students were asked to rate their arousal before and after the game as well as after finishing the stories.

Control Conditions. When it appeared during initial data collection that participants were responding aggressively regardless of the condition, there was concern that the sign up sheet itself may have primed for aggression because it advertised playing a video game. So two additional (control) conditions were collected. In one control condition (game expectant), participants signed up expecting to play a video game. They completed everything in the study before they were given the option to play a video game at the end. In the second control condition (no game play), participants completed all the materials without expecting to play a video game.

Story Stems. Three incomplete stories about potential conflict situations were presented to participants. Two stories were from Bushman and Anderson (2001): “Car Accident” is about a person driving home whose car gets hit from behind when he brakes suddenly for a yellow light. “Persuading a Friend” is about a woman who wants her best friend, who is saving money to buy a stereo, to join her for a beach vacation. “The Room” was a story written by the researchers about a student whose roommate’s laundry is taking over their room despite a promise to take care of it weeks earlier.

Scoring. Participants were asked to complete each story with 20 feelings, actions, thoughts, or comments of the protagonist. These responses were collapsed across type of response and were scored for neutral, aggressive, and prosocial content. Aggressive responses were those that could potentially do harm to the other person in the story (e.g., yelling at them, threatening them, intentionally manipulating them, hurting them or their property). Prosocial responses were those that supported the welfare of the other or of the relationship (e.g., checking to see if the other driver was okay, apologizing, helping the friend buy a stereo, doing the roommate’s laundry, rebuilding the friendship). Neutral responses were those that did not help or hurt the other person and actions that might be expected in the situation (e.g., call for a tow truck, drive to the friend’s house, think about what to do). The three categories (aggressive, prosocial, neutral) were added up across stories. For each participant, the percentage of each type of response out of total responses was calculated and used in the analysis. Participants who had fewer than 50 responses total or more than 70 were not included in the analysis.

Other Variables. In order to monitor the effects of experience, participants were asked how frequently they played video games (6-point Likert-type scale: Never, Rarely, Few times a year, Few times a month, Few times a week, Daily). This information was entered into the analysis. Participants also rated their arousal (5-point Likert-type scale: Not excited at all, A little excited, Half excited, Mostly excited, Very excited). Players rated their arousal before playing, after playing, and after finishing the stories. Both sets of control participants provided their arousal levels at the beginning of the session and after the stories were completed.

Procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to a video game playing condition and tested individually in single rooms with a computer. First they indicated how aroused they felt. Then they played the video game for ten minutes. Afterwards, they wrote down how many points they earned and rated how aroused they felt. Then they completed the three ambiguous story stems. For this task, the instructions from Bushman and Anderson (2001) were used:

Please read each of the following three brief stories. After reading each story, please take a moment to imagine what the person in the story might do, say, think or feel next, if the story were to continue. Then, write down about 20 words or phrases, in the columns provided, that you think describe what would happen next in the story. It is not important which columns you complete, as long as you write in about 20 items for each story.

Everyone read and completed the stories in the same order: The Car Accident, Persuading a Friend, The Room. Following story stem completions, participants rated their arousal and provided demographic information, including their frequency of video game playing.

After the game-playing conditions were collected, two control conditions were collected independently, one after the other. First they indicated how aroused they felt. Then they completed the three ambiguous story stems and again indicated how aroused they felt. Then they completed the demographic information. That concluded the study for the no-game condition. In the expected-game-play condition, participants could then choose to play a video game (none did).

Results

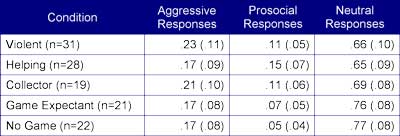

The means and standard deviations for story responses by condition are listed in Table 1.

A MANOVA with post-hoc Tukey HSD tests were used. All analyses were conducted with a significance value of .05.

Table 1. Percentage of Each Response Type (Aggressive, Prosocial, Neutral) by Condition (Violent, Helping, Collector, Game Expectant, No Game)

The primary interest was whether condition influenced responses to story stems. To examine whether condition had the expected effect, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted with aggressive, neutral, and prosocial story responses as dependent variables and four factors: condition (collecting, violent, helping, game expectant, no game), experience playing videogames (6-point Likert-type scale), sex (male, female), and age (18-22).

The multivariate analysis was significant only for condition (Wilks’ lambda =.26, F(12,74.373) = 4.33, p<.0001, eta2 = .37). The other variables were nonsignificant, for experience: p> .98; for sex: p >.18, for age: p > .53. Interactions were nonsignificant (p > .54), except that condition by age approached significance, Wilks’ lambda =.25, F(33,83.197) = 1.50, p=.07, eta2 squared = .37.

The univariate analysis was significant for prosocial responses, F(4,82= 10.08, p<.0001, eta2 =.57, and also for neutral responses, F (4,82)=3.80, p<.013, eta2 =.34; it approached significance for aggressive responses, F (4,82)=2.47, p<.07, eta2 =.25.

Post-hoc analyses were conducted using Tukey HSD. The results are discussed by response type. As predicted, the helping condition generated a higher number of prosocial responses than the other conditions (violent, p <.032; collecting, p<.013; game-expectant, p <.0001, no-game p<.0001). The collecting condition generated significantly more prosocial responses than the no-game condition, p<.002. Both control conditions generated significantly fewer prosocial responses than the violent condition (game-expectant, p <.025; no-game p<.0001).

Among groups there were more neutral responses than any other type of response. However, the two control conditions generated significantly more neutral responses. The expected-game condition generated significantly more than the violence condition, p<.004 and the helping condition, p<.005. The no-game condition generated significantly more neutral responses than the violence condition, p<.001, the helping condition, p <.001, and the collecting condition, p <.02.

Contrary to prediction, there were no significant differences in the number of aggressive responses across conditions (although it approached significance for fewer responses in the helping condition, p >.08 and in the game-expectant, p >.07).

To test whether or not there was a significant difference within conditions for aggressive versus prosocial responses, paired analyses were conducted. There were significantly more aggressive responses than prosocial responses for all conditions (p < .001) except for the helping condition. Within the helping condition there was no significant difference between the number of prosocial and the number of aggressive responses given (p >.54). This finding suggests that the helping condition may have resulted as much from violence suppression as from prosocial priming.

Participants rated their arousal three times: before the game (all 5 conditions), after the game (game-playing conditions), after finishing the stories (all 5). Before playing the videogame, there were no significant differences among groups (p >.08). After playing the game, the three experimental groups were significantly different, with the prosocial condition reporting the highest arousal (Violent M= 2.96 SD=.92; Helping M=3.23, SD=1.07; Collecting M= 2.46, SD=1.21), F(2,70)=3.38, p<.04. After finishing the stories, arousal was significantly different among the five conditions, with the violent condition reporting the highest arousal (Violent M= 2.96 SD=1.11; Helping M=2.56, SD=1.14; Collecting M= 2.39, SD=1.29; Game Expectant M= 2.20 SD=.89; No Game M= 2.00 SD=1.02), F(4,100)=2.52, p<.04. To examine potential arousal effects, a correlations table was examined of the key variables. Only one arousal variable was significantly correlated with anything: arousal after the game was correlated with the helping condition.

Discussion

This study compared the effects of playing a helping video game with violent and neutral video games on reported thoughts, feelings and behaviors attributed to story characters during story completions. University students, freshman to senior, were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: play violent game, play helping game, play collecting game. Two control conditions were also collected: expect to play a game, and not play a game. Students completed stories which were then analyzed for aggressive, prosocial and neutral responses attributed to story characters. Students varied in their video gaming experience and so this, along with sex and age, were included in the analysis. There were no significant multivariate effects for aggressive responses, or for video game experience, age or sex. There was a significant effect for prosocial responses in the helping game condition and there were greater numbers of neutral responses in both control conditions. The results are discussed in two broad categories.

Playing a Helping Game Had a Positive Influence on Prosocial Attribution

The helping condition had an effect in the expected direction, significantly increasing the number of prosocial responses in comparison to the other conditions. Those who played the helping game were more likely to describe the story characters as having concern and empathy for others in the story. Prosocial video game playing had at least short-term priming effects for prosocial thoughts, feelings, and attributed behaviors. Although the results are preliminary, they fit with other research on the positive effects of prosocial media (Hogan & Strasburger, 2008).

It is not clear what the prosocial mechanism was for increased prosocial responses in the helping condition. Perhaps it was related to identifying with the role adopted (helper of others) and subsequent self views (Uhlmann & Swanson, 2004) or the continuous practice (visual, proprioceptive, goal attempts) of helping others that activated a network of prosocial concepts through spreading activation. In the same way that violent game play increases a hostile expectancy bias (Bushman & Anderson, 2002), playing a prosocial video game may increase a prosocial expectancy bias so that a person subsequently is more likely to ascribe positive motives to other people’s behavior.

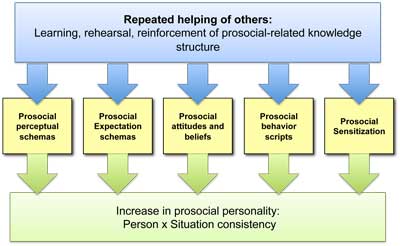

One also might go so far as to propose a mirror to the General Aggression Model such as a Generalized Prosocial Model. Figure 1 displays what such a model might look like. There is converging evidence from multiple research programs for such a model. For example, in terms of short-term effects, mood induction research shows that when a positive mood is induced, individuals are more likely to be helpful and generous to other people (e.g., Isen, 1970; Isen & Levine, 1972; see Isen, 2002 for a review); they are more likely to be friendly and sociable (e.g., Veitch & Friffitt, 1976) and more socially responsible (e.g., Berkowitz, 1972). Induced positive affect is also related to more flexible and open thinking (Isen, Daubman & Nowicki, 1987). Frederickson (2001) suggests a broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions (specifically joy, contentment, interest, love) in which thought repertoires are increased and personal resources are extended during positive emotional experience.

Figure 1. Proposed General Prosocial Model

Lapsley and Narvaez (2004; 2005; Narvaez, Lapsley, Hagele & Lasky, 2006) document the more long-term effects of a prosocial or moral personality. One has a moral personality to the extent that moral constructs—such as being good, fair, and/or just—are central and essential to one’s self-understanding. Persons with moral identities process social information with a set of chronically accessible moral schemas, evident in the type of spontaneous trait inferences made and in moral evaluations of others’ behavior (i.e., prosocial expectations; Narvaez et al., 2006). One develops moral scripts, schemas, dispositions and orientations through repeated practice of moral goal implementation, prosocial focusing and acting. Social knowledge structures develop over time through such experience, shaping perception, interpretation, judgment and response. For example, each rehearsal of helping another person provides a trial for learning about the benefits of building social relations, for understanding that cooperation and compassion are normal reactions to others and that the world can be a benevolent place. Chronically accessible categories mark a dispositional preference or readiness to discern the moral aspects of experience and contribute to a discriminative facility in selecting situationally-appropriate behavior accessible through situational priming (Lapsley & Narvaez, 2006), which combine to influence social perception (Bargh, Bond, Lombardi & Tota, 1986). In fact, adolescents who practice community service in high school are more likely to develop a moral identity (i.e., prosocial self-expectations; Hart & Fegley, 1995) and continue community service as adults (i.e., prosocial scripts; Youniss, McLellan & Yates, 1997). Parents who use inductive reasoning and respond to their children with empathy and discussion are more likely to raise children with conscience who act pro-socially (i.e., prosocial sensitization; Thompson, 2006). Children whose parents regularly point out how their positive behavior relates to their (moral) identity are more likely to develop prosocial dispositions (i.e., prosocial perceptual schemas; Grusec & Redler, 1980). In these ways, the types of guidance one receives and the types of practice one undertakes leads to readily-primed dispositional orientations.

Is There a Cultural Dispositional Tendency for a Hostile Expectancy Bias?

All conditions produced more neutral responses than aggressive or prosocial responses, with the two control conditions producing significantly more neutral responses than any game condition. Unexpectedly, there were no significant differences for aggressive responses across conditions. The violent condition did not significantly increase the number of aggressive responses in comparison to the other conditions. Instead, there were more aggressive responses than prosocial responses across all conditions. This suggests that the university student participants may have entered the experiment with a high baseline level of aggression or a generalized hostile expectation bias. Further research is needed to examine these possibilities.

Self-reported arousal was unrelated to the study variables. Interestingly, those in the helping condition reported significantly greater arousal after playing the game than those in the other game-playing conditions, contrary to what might be expected based on prior research (see Gentile & Anderson, 2007). Perhaps this finding was due to chance or perhaps the pressure of healing others may have been arousing in some fashion. However, after an interval (filled with writing endings to the stories), arousal for the violent condition was greater than for the other conditions. So in this case there may have been a delayed effect.

Conclusion

Video games cultivate schemas about the social world for better or for ill. Violent video game play can lead to a hostile attribution bias based on aggressive schemas and attitudes. In contrast, playing prosocial video games may develop prosocial schemas and increase the likelihood of thinking, feeling, and behaving pro-socially, leading to a prosocial expectancy bias. Through promoting extensive practice, video games foster perceptions, attitudes and responses in players, who learn affordances for action in the real world. When a person practices helping actions she develops one set of affordances; when she practices violent action, she develops a different set of affordances. Aristotle may have been correct in pointing out the importance of selecting one’s friends and activities carefully; they help a person develop sensibilities and habits for either virtue or vice.

References

Anderson ,C.A. (2004). An update on the effects of playing violent video games. Journal of Adolescence, 27, 113-122.

Anderson, C. A., & Bushman, B. J. (2001). Effects of violent video games on aggressive behavior, aggressive cognition, affect, physiological arousal, and prosocial behavior: Psychological Science, 12, 353-359.

Anderson, C., Berkowitz, L., Donnerstein, E., Huesmann, L.R., Johnson, J.D., Linz, D., Malamuth, N.M., & Wartella, E. (2003). The influence of media on youth. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4, 81-110.

Anderson, C. A., & Dill, K. E. (2000). Video games and aggressive thoughts, feelings, and behavior in the laboratory and in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78 (4), 772-790.

Anderson, C.A., Gentile, D.A., & Buckley, K.E. (2007). Violent video game effects on children and adolescents: Theory, research and public policy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bargh, J.A., Bond, R.N., Lombardi, W.J. & Tota, M.E. (1986). The additive nature of chronic and temporary sources of construct accessibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 869-878.

Berkowitz, L. (1972). Frustrations, comparisons, and other sources of emotion aroused as contributors to social unrest. Journal of Social Issues, 28, 77-92.

Bushman, B.J., & Anderson, C.A. (2002). Violent video games and hostile expectations: A test of the general aggression model. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 1679-1686.

Chambers, J.H. & Ascione, F.R. (1987) The effects of prosocial and aggressive videogames on children’s donating and helping. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 148, 499−505.

Fontana, L., & Beckerman, A. (2004). Childhood Violence Prevention Education Using Video Games. Information Technology in Childhood Education Annual 1, 49-62.

Frederickson, B. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The. broaden and build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56, 218-226.

Funk, J.B., Baldacci, H.B., Pasold, T., & Baumgardner, J. (2004). Violence exposure in real-life, video games, television, movies, and the internet: Is there desensitization? Journal of Adolescence, 27, 23-39.

Gentile, D.A., & Anderson, C.A. (2006). Violent video games: The effects of youth, and public policy implications. In N.E. Dowd, D.G. Singer, & R.F. Wilson (Eds.), Handbook of culture and violence. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Hart, D., & Fegley, S. (1995). Prosocial behavior and caring in adolescence: Relations to self-understanding and social judgment. Child Development, 66, 1346-1359.

Grusec, J.E., & Redler, E. (1980). Attribution, reinforcement, and altruism: A developmental analysis. Developmental Psychology, 16, 525-534.

Hogan, M.J. (2001). Parents and other adults: Models and monitors of healthy media habits. In D.G. Singer, & J.L. Singer (Eds.), Handbook of children and the media. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Hogan, C., & Strasburger, V. (2008). Media and prosocial behavior in children and adolescents. In L. Nucci & D. Narvaez (Eds.), Handbook of Moral and Character Education (pp. 537-553). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Huesmann, L.R., Moise-Titus, J., Podolski, C., & Eron, L.D. (2003). Longitudinal relations between children’s exposure to TV violence and their aggressive and violent behavior in young adulthood: 1977-1992. Developmental Psychology, 39, 201-221.

Isen, A. M. (1970). Success, failure, attention and reactions to others: The warm glow of success. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 17, 107-112.

Isen, A.M. & Levin, P.F. (1972). The effect of feeling good on helping: Cookies and kindness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 21, 385-388.

Isen, A. M. (2002). A role for neuropsychology in understanding the facilitating influence of positive affect on social behavior and cognitive processes. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of Positive Psychology (pp. 528-554). New York: Oxford University Press.

Veitch, R. & Friffitt, W. (1976). Good news—bad news: Affective and interpersonal effects. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 8, 69-75.

Isen, A.M., Daubman, K.A., & Nowicki, G.P. (1987). Positive affect facilitates creative problem solving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 1122-1131.

Johnson, J.G., Cohen, P., Smailes, E.M., Kasen, S., & Brook, J.S. (2002). Television viewing and aggressive behavior during adolescence and adulthood. Science, 295, 2468-2471.

Kunkel, D., & Zwarum, L. (2006). How real is the problem of TV violence? In N.E. Dowd, D.G. Singer, & R.F. Wilson (Eds.), Handbook of children, culture, and violence. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Lapsley, D. & Narvaez, D. (2004). A social-cognitive view of moral character. In D. Lapsley & D. Narvaez (Eds.), Moral development: Self and identity (pp. 189-212). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Narvaez, D., & Lapsley, D. (2005). The psychological foundations of everyday morality and moral expertise. In D. Lapsley & Power, C. (Eds.), Character Psychology and Character Education (pp. 140-165). Notre Dame: IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

Lapsley, D. K. & Narvaez, D. (2006). Character Education. In Vol. 4 (A. Renninger & I. Siegel, volume eds.), Handbook of Child Psychology (W. Damon & R. Lerner, Series Eds.) (pp. 248-296). New York: Wiley.

Mathews, V.P., Kronenberger, W.G., Wang, Y., Lurito, J.T., Lowe, M.J., & Dunn, D.W. (2005). Media violence exposure and frontal lobe activation measured by functional magnetic resonance imaging in aggressive and nonaggressive adolescents. Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography, 29 (3), 287-292.

Narvaez, D., Lapsley, D., Hagele, S., & Lasky, B. (2006). Moral chronicity and social information processing: Tests of a social cognitive approach to the moral personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 40, 966–985.

Robinson, T.N., Wilde, M.L., Navracruz, L.C., Haydel, K.F., & Varady, A. (2001). Effects of reducing children’s television and video game use on aggressive behavior: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, 155 ( 1), 17-23.

Thompson, R. A. (2006). The development of the person: Social understanding, relationships, self, conscience. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of Child Psychology (6th Ed.), Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development (N. Eisenberg, Vol. Ed.). New York: Wiley.

Uhlman, E. & Swanson, J. (2004). Exposure to violent video games increases automatic aggressiveness. Journal of Adolescence, 27, 41-52.

Yates, M., & Youniss, J. (1996a). A developmental perspective on community service in adolescence. Social Development, 5, 85-111.

Youniss, J., McLellan, J.A. & Yates, M. (1997). What we know about engendering civic identity. American Behavioral Scientist, 40, 620-631

First Author Contact Information:

Department of Psychology

118 Haggar Hall

University of Notre Dame

Notre Dame IN 46556

dnarvaez@nd.edu

Appendix

The Room

Justin and his roommate Steve have lived together since their freshman year of college. They had been good friends until this, their junior year. They were making new friends in their majors and spending less and less time together.

Steve noticed that his side of the room was starting to be overtaken with Justin’s dirty clothes. When he first mentioned this to Justin, Justin said that he had a lot of homework and would get around to his laundry after that. But that was two weeks ago. Today, Steve found Justin’s clothes from yesterday under his desk.